What do you think?

Rate this book

127 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1925

The bookcase of early childhood is a man’s companion for life. The arrangement of its shelves, the choice of books, the colors of the spines are for him the color, height, and arrangement of world literature itself. And as for books which were not included in that first bookcase – they were never to force their way into the universe of world literature. Every book in the first bookcase is, willy-nilly, a classic, and not one of them can ever be expelled.

I was troubled and anxious. All the agitation of the times communicated itself to me. There were strange currents loosed about me – from the longing for suicide to the expectation of the end of the world. The literature of problems and idiotic universal questions had just taken its gloomy malodorous leave, and the grimy hairy hands of the traffickers in life and death were rendering the very words life and death repugnant. That was in very truth the night of ignorance! Literati in Russian blouses and black shirts traded, like grain dealers, in God and the Devil, and there was not a single house where the dull polka from The Life of Man, which had become a symbol of vulgar tawdry symbolism, was not picked out with one finger on the piano. For too long the intelligentsia had been fed on student songs. Now it was nauseated by its universal questions. The same philosophy from a beer bottle!

There’s no disputing it: we should be grateful to Wrangel for letting us breathe the pure air of a lawless sixteenth-century Mediterranean republic. But it was not easy for Attic Theodosia to adjust herself to the severe rule of the Crimean pirates.

He thought of Petersburg as his infantile disease – one had only to regain consciousness, to come to, and the hallucination would vanish: he would recover, become like all other people, even – perhaps – get married… Then no one would dare call him “young man.” And he would be through with kissing ladies’ hands. They’d had their share! Setting up their own Trianon, damn them! Let some slut, some old bag, some shabby feline stick her paw out to his lips and, by the force of long habit, he would give it a smack! Enough! It was time to put an end to his lapdog youth.

The cheap vegetable pigments of Van Gogh were bought by accident for twenty sous.

Van Gogh spits blood like a suicide in furnished rooms. The floorboards in the night cafe are tilted and stream like a gutter in their electric fit. And the narrow trough of the billiard table looks like the manger of a coffin.

I never saw such barking colors!

"If a physicist should conceive of the desire, after taking apart the nucleus of an atom, to put it back together again, he would be like the partisans of descriptive and explanatory poetry, for whom Dante represents, for all time, a plague and a threat."

Suspecting that his guards had received orders from Moscow to poison him, he refused to eat any meals (they consisted of bread, herring, dehydrated cabbage soup, and sometimes a little millet). His fellow deportees caught him stealing their bread rations. He was subjected to cruel beating-up until it was realized that he was really insane. In Vladivostok transit camp his insanity assumed a still more acute form. He still feared being poisoned and began again to steal food from his fellow inmates in the barracks, believing that their rations, unlike his, were not poisoned. Once again he was brutally beaten up. In the end he was thrown out of the barracks; he went to live near the refuse heap, feeding on garbage. Filthy, with long, gray hair and a long beard, dressed in tatters, with a mad look in his eyes, he became a veritable scarecrow of the camp.

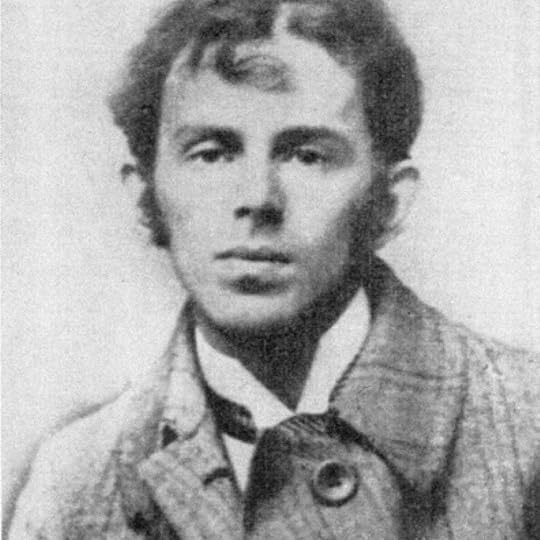

'How do you do, Ivan Ivanovich?'The novella The Egyptian Stamp is the only extant piece of fiction produced by Mandelstam. The story is told in an absurdly digressive style that tends to obscure the two relatively straightforward narrative arcs, neither of which are of much significance. But there are other layers to the work should one be inclined to dig below the surface. Brown dissects the novella quite thoroughly in his introduction, providing insight into the meaning of the work and postulating that it is actually closer to autobiography than pure fiction, based on his knowledge of Mandelstam’s life, compatriots, and literary antecedents.

'Oh, all right, Pyotr Petrovich. I live in the hour of my death.'

When I was a child a stupid sort of touchiness, a false pride, kept me from ever going out to look for berries or stooping down over mushrooms. Gothic pinecones and hypocritical acorns in their monastic caps pleased me more than mushrooms. I would stroke the pinecones. They would bristle. They were trying to convince me of something. In their shelled tenderness, in their geometrical gaping I sensed the rudiments of architecture, the demon of which has accompanied me throughout my life.Mandelstam’s passionate commitment to literature and his love of language results in an unusually strong bond between reader and writer. He is the kind of writer who one comes to think of as a friend. I felt that when I first read his poetry, and I felt it even more acutely as I read his prose. After so long of being silenced, it is good to know that so many of his words are finally out there for the world to read.

And in this wintry period of Russian history, literature, taken at large, strikes me as something patrician, which puts me out of countenance: with trembling I lift the film of waxed paper above the winter cap of the writer. No one is to blame in this and there is nothing to be ashamed of. A beast must not be ashamed of its furry hide. Night furred him. Winter clothed him. Literature is a beast. The furriers—night and winter.