What do you think?

Rate this book

335 pages, Kindle Edition

First published March 1, 2010

"Foreign traders in the south of Japan had introduced the Japanese to the concept of the matchlock gun, and the new weapon had swiftly caught on. The samurai were not unfamiliar with gunpowder – they had, after all, suffered dearly from its use in the Mongol invasion – but the concept of a portable, light arquebus that could be carried by a single soldier was new to them. The first guns had arrived in the early 1540s on the island of Tanegashima, a remote outpost just off the southwest coast of Japan. There, Portuguese sailors had demonstrated their arquebuses to the enraptured local warlord, who ordered his master swordsmith to make as many copies as he could. The swordsmith was initially stumped by the technology required, but after legendarily selling his daughter to another set of Portuguese traders in exchange for further lessons, he was soon churning out reasonable facsimiles of the Portuguese guns. The Japanese began calling the weapons tanegashima, after the place of their ‘discovery’.As are the many internal wars between clans that took place after Kublai Khan's failed Mongol invasion:

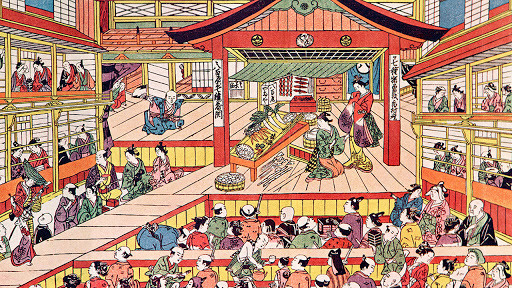

"There are two keywords for the Country at War period. One is daimyō, literally ‘great names’ – the new breed of local lords, each supreme in his own domain, constantly jockeying for position. The other is gekokujō, ‘the low dominating the high’ – a reference by many disinherited members of the old order to the rapid, brutal social mobility of the time. Japan entered one of its periodic purges of noble houses: once-great names sank with the declining fortunes of their families, and entire clans were wiped out. The emperor, of course, was powerless to intervene, and the Shōgun unable to fulfil the conditions of his title. The country would not stabilize again until a single individual could gather together the fragmented clans and domains and unite them all, thereby allowing for the proclamation of a new Shōgunate. The rise of such an individual would take a century, as the small clans fought and merged to form bigger clans, until eventually all Japan was split into only a handful of rival factions, fighting to determine who was the true ruler..."

"Guns were not the only thing that had arrived from the West. First the Portuguese, then the Spanish and then the Italians sent Christian missionaries, determined to spread the Bible to the Japanese. Exotic and alien, Christian belief achieved virulent proportions in Japan, with such large number of converts that Japan effectively became the largest non-European diocese in the world by the end of the sixteenth century.

The rise and fall of the missionaries during the period 1549–1650 is often known as ‘Japan’s Christian Century’, a problematic term.1 In the south-west, in particular on the island of Kyūshū, there was a strong upwelling of interest, particularly after missionary orders stopped targeting the poor, sick and needy, and adopted the Buddhists’ strategy of preaching to the upper classes, in the hope that their subjects would follow their lead. This led to a couple of generations of Japanese nobility with Christian names, as converts adopted baptismal names from the distant West – among others, we see a Dario Sō in the ruling clan of Tsushima, a lord André of Arima, and the zealous lord Bartholomew of Ōmura, who briefly granted Jesuit missionaries authority over the harbour town of Nagasaki."

"...A warrior elite does not dominate a state for 700 years without leaving a long shadow, for good or ill. However, we should not be surprised if we are unable to precisely classify the nature of the samurai, since even the Japanese have never been able to agree among themselves about the true nature of Bushidō. The ‘way of the samurai’, whatever it may be, is an integral component of the soul of Japan. Nothing happens in modern Japan that is not in imitation of it, or reaction to it. Loyalty or opposition to the way of the samurai takes as many forms as there were sides in the Meiji Restoration, but it is always there, like the Emperor himself, ancient, unknowable and enduring..."