― “Admiral Ernest King retired to his cabin on the evening of Saturday, January 10, 1942. Much to the frustration of the sixty-three-year-old Ohioan, who served as commander in chief of the U.S. Fleet. Christmas and New Year’s had passed without any reprieve from the bad news that dominated the Pacific.”

― James M. Scott, Target Tokyo: Jimmy Doolittle and the Raid That Avenged Pearl Harbor

Admiral King’s frustration reflected the feelings of desperation that plagued President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his military leaders in the months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The surprise military attack on the US naval base at Pearl Harbor had decimated US naval power in the Pacific. All nine of the battleships stationed at Pearl Harbor sustained significant damage. According to the author, the Japanese Navy was now “more powerful in that ocean than the combined navies of the United States, Great Britain and the Netherlands.”

Often lost in the discussion about that infamous day is that, shortly after the Pearl Harbor attack, Japanese dive bombers struck American bases on Guam and Wake Island. Japanese bombers and fighters also attacked Clark Field, the main American air base in the Philippines, destroying or badly damaging all the B-17 Flying Fortresses located there. In the ensuing struggle for the Philippines, the President warned Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall to “anticipate the possibility of disaster,” writes author James M. Scott.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his military leaders were desperate to come up with a retaliatory measure that would help lift national morale. “The Japanese needed to experience the same shock, humiliation, and destruction that America had suffered.”

― “‘The President was insistent,’ (Lt. Gen. “Hap”) Arnold recalled, ‘that we find ways and means of carrying home to Japan proper, in the form of a bombing raid, the real meaning of war.’”

― James M. Scott, Target Tokyo

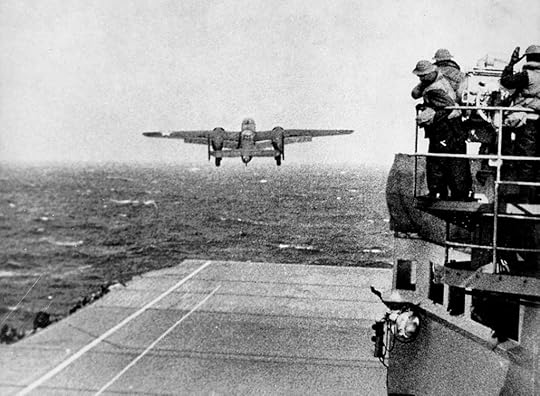

It was Captain Francis Low, Admiral Ernest King’s operations officer, who came up with the idea of putting bombers on a carrier to bomb the mainland of Japan. Working with Captain Donald Duncan, they determined that the twin-engine B-25 was best suited for the mission. Its wingspan was short enough to take off a carrier without hitting the tower. When General Arnold ran the idea by his staff troubleshooter, forty-five-year-old Lt. Colonel Jimmy Doolittle, he received an enthusiastic endorsement. At the same time, American newspapers thought the possibility that “America might actually strike back at Japan was viewed as impossible, if not laughable.”

― “The plan laid out by General Arnold was the perfect operation for Jimmy Doolittle, a man who on first glimpse did not appear to be such a formidable fighter. The gray-eyed Doolittle stood just five feet four—two inches shorter than Napolean.”

― James M. Scott, Target Tokyo

Doolittle had captured national attention over the years as a stunt and racing pilot in an age when Americans were fascinated with airplanes. He was chosen to lead the mission against Japan. He asked for volunteers for the dangerous mission, but he could not tell the men what that mission entailed. Doolittle couldn’t even tell his own wife. Nonetheless, eighty men volunteered.

With the help of a naval aviator with carrier experience, the men trained for weeks on short takeoffs. It wasn’t until they had boarded the aircraft carrier USS Hornet and were out of radio range of San Francisco that the volunteers and the crew of the Hornet were told of the mission. Their mission, the men were told, was to bomb Tokyo and other key cities in Japan. Excitement coursed throughout the ship; they would attack at the very heart of the enemy.

Readers who are only moderately familiar with the raid might expect that the rest of the book covers the successful raid and the return of the pilots to fame and acclamation. However, the story isn’t quite that simple. Not by a long shot. The Hornet encountered the picket boat Nitto Maru 800 miles from the coast of Japan. Fearing that the task force had been reported, Admiral Halsey had the raiders prepare for takeoff—300 miles further out from Japan than had been planned.

Fuel would now be a very real concern. After dropping their bombs, the sixteen bombers planned to fly to air bases in China, flying far enough into China to avoid Japanese controlled Manchuria. Heading into a stiff headwind, most of the planes were using fuel at a rate faster than expected.

― “The gravity of the raid sunk in for many. ‘We figured there was only a 50-50 chance we would get off the Hornet,’ Nielsen remembered. ‘If we got off , there was a 50-50 chance we’d get shot down over Japan. And, if we got that far, there was a 50-50 chance we’d make it to China. And, if we got to China, there was a 50-50 chance we’d be captured. We figured the odds were really stacked against us.’”

― James M. Scott, Target Tokyo

After the bombers reached Japan, the navigators had some trouble finding their targets, despite having extensively reviewed maps of their targets. Encountering anti-aircraft fire and being harassed by fighter planes, most of the planes ended up choosing targets that seemed best to them. Many of the bombs missed even these targets, and many homes and even a school and a hospital were struck. The casualties included some children.

Perhaps the most successful attack was a strike on the former submarine tender Taigei that was in a shipyard being converted into a new carrier. Damage to the ship would set back its conversion four months. While the raid was not a huge success in terms of targets damaged or destroyed, the Japanese had failed to shoot down a single raider. After dropping their bombs, the raiders turned their planes toward China.

The second half of the book covers the flight of the planes to China, although one chose to go to Russia. To be honest, this is when the story really gets interesting. Although the news of the bombing was received with much rejoicing back in the States, the bomber crews were facing the toughest part of their mission. Reaching the coast of China at night, in the middle of bad weather, and running out of fuel, the pilots and crew faced the difficult task of bailing out of their planes.

― “Cole hovered over the hatch, staring down at the dark void. ‘I was one scared turkey,’ he recalled. ‘Being in an airplane that was about to run out of fuel and looking down at the black hole that would exit you into a foreign land, in the dark of the night, in the middle of bad weather was not exactly what one envisioned when enlisting.’”

― James M. Scott, Target Tokyo

Of the fifteen planes that headed for China, none made it to the landing strips that had been chosen. All of the planes crashed into the coastal area or the mountains. A few crewmen who did not bail out were killed and some seriously injured. While most of the crews found their way to Chinese resistance fighters or American missionaries, two crews were captured by the Japanese and imprisoned. The crew of one plane was taken to Tokyo, and three of them were executed. The others were nearly starved to death.

The assistance given to the American pilots by the Chinese led to serious reprisals by the Japanese. A three-month campaign of terror was conducted in which “local farmers and villagers were raped, murdered, and poisoned as a consequence of America’s raid.” The United States had purposely withheld details of the raid from Chiang Kai-shek, knowing the Japanese would certainly retaliate. The vengeance of the Japanese claimed an estimated 250,000 lives—a terrible cost for the Chinese.

Author James M. Scott has written a gripping, highly readable account of the effort and sacrifice that went into the Doolittle raid. This is a must-read for any history fan.