What do you think?

Rate this book

144 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1946

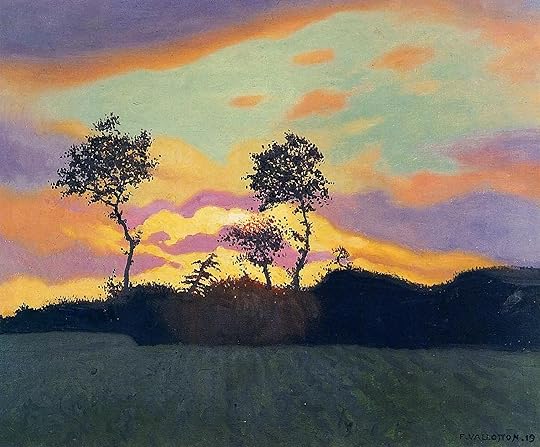

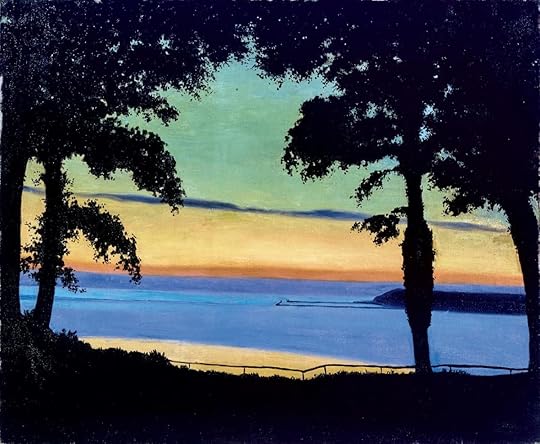

“In Porquerolles, things were hostile to him. He had tried in vain to lessen their impact. Down south, all the time, he had felt as if there was a tremendous chaos around him, a kind of life that was too vivid, so that the slightest contact with it made his blood pulse more quickly, and prompted a rising fever inside him.”

The Mahé Circle is a sort of masterpiece; one says “sort of” because the book does not call itself to our attention in any purely literary way. Simenon’s uniqueness is that he created high literature in seemingly low forms. This novel, like most of the romans durs, reads like a piece of pulp fiction: it is brief, fast-paced, with an air of the slapdash that is, however, wholly deceptive. True, Simenon wrote fast, and revised little. Yet his artistry is supreme. The account in this book of old Madame Mahé’s descent into illness and death is a sublime piece of writing, as good, in its unforced and unemphatic way, as anything in Proust or even Flaubert.He's right about the death of Madame Mahé: there is a tenderness in this extended scene that nothing in the novel quite anticipates. It's been a stressful month, and I'm finding Simenon the perfect balm for an anxious spirit.