What do you think?

Rate this book

320 pages, Paperback

First published January 8, 2015

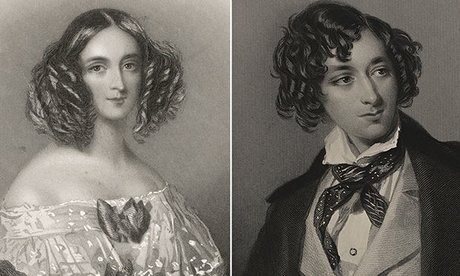

Before he met Mary Anne, Benjamin Disraeli was a dreamer of a young man, the son of the writer Isaac D'Israeli, and, honestly, a bit of a feckless waste of space for the first twenty-four years of his life. He had an unsurprisingly anti-Semitic experience at school* and never went to university**. He seemed to mostly prefer bumming around obsessing about Byron much of the time and writing occasionally. He eventually tried his hand at writing popular "silver fork" novels (read: chick lit/aspirational fantasy) of the 1830s and got laughed out of town on his first attempt (literally out of the country, actually- he fled to Europe to do a Byronic Grand Tour to escape his humiliation). He had some successive novels that did moderately well when his ego recovered a few years later, and his assumption of leadership of the "Young England" group of writers made his reputation grow a bit (these writers were, as far as I can make out, sort of vaguely for reform, but mostly about the importance of giving people heroes and arguing that writers would make amazing statesmen). However, his attempts to parley this into political success were similarly at first unsuccessful. By his mid-thirties he was also deeply in debt to the tune of thousands of pounds and perhaps about to be thrown into jail by his creditors- that this didn't happen is only thanks to his first electoral win, in which Parliamentary privilege prevented him from being prosecuted. Which is how he met Mary Anne.

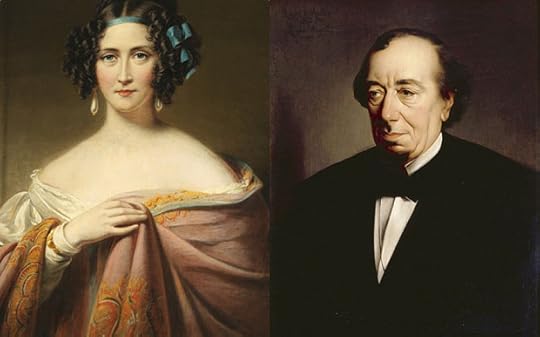

Before he met Mary Anne, Benjamin Disraeli was a dreamer of a young man, the son of the writer Isaac D'Israeli, and, honestly, a bit of a feckless waste of space for the first twenty-four years of his life. He had an unsurprisingly anti-Semitic experience at school* and never went to university**. He seemed to mostly prefer bumming around obsessing about Byron much of the time and writing occasionally. He eventually tried his hand at writing popular "silver fork" novels (read: chick lit/aspirational fantasy) of the 1830s and got laughed out of town on his first attempt (literally out of the country, actually- he fled to Europe to do a Byronic Grand Tour to escape his humiliation). He had some successive novels that did moderately well when his ego recovered a few years later, and his assumption of leadership of the "Young England" group of writers made his reputation grow a bit (these writers were, as far as I can make out, sort of vaguely for reform, but mostly about the importance of giving people heroes and arguing that writers would make amazing statesmen). However, his attempts to parley this into political success were similarly at first unsuccessful. By his mid-thirties he was also deeply in debt to the tune of thousands of pounds and perhaps about to be thrown into jail by his creditors- that this didn't happen is only thanks to his first electoral win, in which Parliamentary privilege prevented him from being prosecuted. Which is how he met Mary Anne. And in the end, it seemed, after twenty years, it was real. They got old, and the last five years of their marriage was everything they pretended it was for years before that, everything Mary Anne had ever wanted and only sometimes got from him, everything Disraeli wanted to be and only sometimes had the focus and time to follow through on. When offered a peerage during these years, Disraeli asked that it go to his wife instead, so she proudly became Viscountess Beaconsfield, able to look down her nose at her detractors at last. At this time, Disraeli would write her just because he missed her. Once, when they were both ill, they wrote back and forth to each other in their sickbeds on separate floors because they were too ill to be moved- Disraeli, by the way, had become ill after sitting up at her bedside for many days. And his last note to her, in the midst of her final illness, is quietly moving in its revelation of how truly he had become attached to her:

And in the end, it seemed, after twenty years, it was real. They got old, and the last five years of their marriage was everything they pretended it was for years before that, everything Mary Anne had ever wanted and only sometimes got from him, everything Disraeli wanted to be and only sometimes had the focus and time to follow through on. When offered a peerage during these years, Disraeli asked that it go to his wife instead, so she proudly became Viscountess Beaconsfield, able to look down her nose at her detractors at last. At this time, Disraeli would write her just because he missed her. Once, when they were both ill, they wrote back and forth to each other in their sickbeds on separate floors because they were too ill to be moved- Disraeli, by the way, had become ill after sitting up at her bedside for many days. And his last note to her, in the midst of her final illness, is quietly moving in its revelation of how truly he had become attached to her: