While this book may not be the only book about the subject one would want to read, it certainly demonstrates that historian Dan Jones has been able to profitably expand upon his interest in the Plantagenet dynasty. In many ways, the author's previous work relating to the political history of the High Middle Ages in England serves as an appropriate context to this book, and the author wisely shares this context with the reader who may not be familiar with the Plantagenet origin of the problems that led to the civil war in England that produced the famous document. Also wisely, the author notes that the Magna Carta quickly became a symbol beyond its original importance, as it was originally an unsuccessful peace treaty that sought to reconcile King John with his barons and later became a standard by which the powerful elements within England (and elsewhere) ensured that government was responsible to the people, or at least the people who mattered in a political sense. If the document is now seen as democratic and egalitarian in nature, that is because of where we are and not because of what it was intended to do in the first place, something the author is right to point out.

As a book, this history is short and enjoyable to read, coming in at less than 250 pages even if one includes the appendices, which I think important to read to appreciate the history of the time. The book is divided into four larger parts and further chapters. After an introduction, the book begins with the origins of the problems within England that led to the Magna Carta (I), including a chapter on the rise of the Plantagenet dynasty (1), the contrast between Richard and John with regards to their success against French efforts (2), the years of interdict and John's intimidation of nobles in England (3), and the crisis and catastrophe of the Bouvines campaign (4). After this the author looks at the opposition between the barons and John (II) in a troubled meeting at the Temple Bar (5), John's taking of the cross as a way to buy time (6), the confrontation between the two forces (7), and the position of London as supporting the opposition (8). Then the author examines the role of the Magna Carta in the rule of law (IV), with a look at the events of Runnymede (9), the document itself (10), England as being under siege by the French army (11), and the endgame of John's life (12). The book then closes with two chapters that look at the afterlife of the document (V) (13, 14) as well as a few appendices that contain the 1215 text, its enforcers, and its use and portrayal in the 800 years or so after it was agreed to.

What is it that allowed the Magna Carta to be a symbol of liberty? For one, it demonstrated that in England at least, the monarch was not powerful enough to completely dominate the political space and had to at least seek the approval of the important people of the nation for military efforts and taxation. The limits on the royal prerogative, maintained and expanded through the centuries, eventually provided the space to allow for the advancement of other social classes from unfree to free status. The principles of no taxation without representation and the importance of placing limits on the authority of government then traveled with the English overseas and led to limitations on the imperial domination of settler colonies inhabited by free folk who were jealous of their freedom and their rights. All of this is worth remembering, even as the author makes it clear that the Magna Carta itself was not an egalitarian document and in some cases at least--with regards to Jews and women--rolled back the rights and protections in such cases in order to safeguard the interests of the restive and rebellious barons. Yet, paradoxically, it was in ensuring the rights of those elite barons that ended up providing a model by which rights could, eventually, be expanded far beyond the narrow range of the population that was originally spoken of in the document, and that is worth celebrating.

1297 Magna Carta at the U.S. National Archives

1297 Magna Carta at the U.S. National Archives Massachusetts Seal (circa 1775)

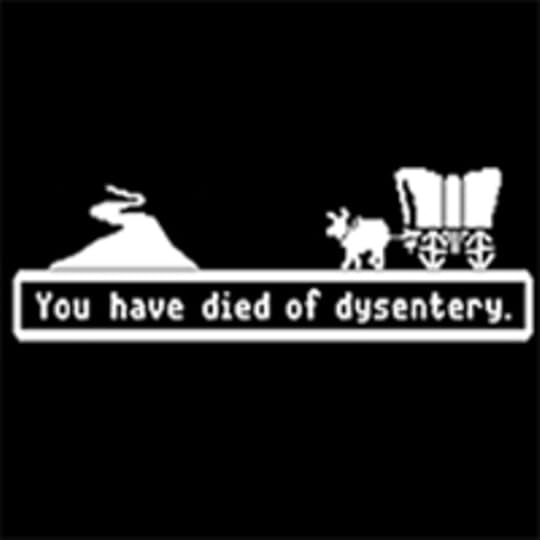

Massachusetts Seal (circa 1775)  Game over for King John

Game over for King John