Tuhle knížku jsem četl ve vlaku do Českých Budějic, což zřejmě nemá na nic vliv.

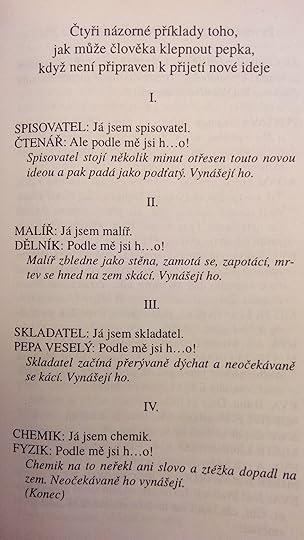

Daniil Charms byl takovej ruskej Vian, stejně jako jsou české hranolky německý pommes frites. V této sbírce jsou divadelní hry, pohádky, mikropovídky, tedy naprosto všechno. Někdy je to slabší, někdy silnější, stejně jako jégr. Ten je taky jednou s red bullem a někdy zase bez. Po obojím se vám zatočí hlava, ovšem po přečtení této knihy vás nebudou budit policajti na ulici před bufetem v Českých Budějovicích, což se mi za celej život minulej týden rozhodně nikdy nestalo.