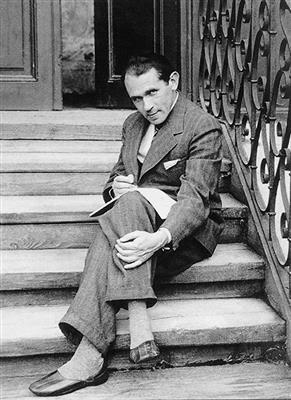

This is an extraordinary work by a truly amazing writer. Bruno Schulz lived in Poland until he was killed by the Nazis (there are two different stories of how he died, one more 'romantic' than the other; no matter, he ended up with others in an unmarked grave). He published two major and amazing works, Cinnamon Shops also known as Street of Crocodiles, and The Sanitorium Under the Hourglass.

This is some of the most exuberant and unique prose you'll ever encounter. It's magical surrealism, untethered, buoyant. It's so unique I struggled with it for the first 94 pages feeling like I was missing something until aha! it came together for me. That is my brain on Schulz; your mileage will vary and you'll likely fall right into the book and not want to come out again. Once I realized what, how much Schulz did here I started again on the first page and took one of the most remarkable literary journeys of my life.

There are two translations. I learned that my GR friend Matthew Appleton, who recommended this book to me (can never thank you enough!) and all of the others whose reviews I savored read a different translation than I did. Mine, by Madeline Levine, is from 2018 and done in cooperation with Polish scholars and the few background materials that exist on Schulz. I won't go into it here but each has its beauty and assets. Levine's being newer and focused more on Schulz's literary techniques including alliteration is said to be definitive. From what I've read each is a win for different reasons and I would very much like to read the other sometime.

The edition I have includes the only other two stories that survive. There is talk he gave his work to someone and to this day there is someone searching but it's likely lost to posterity. In any case the two other stories seem like practice for two in the main works and are not as beautifully written.

The other editions are illustrated because he was a visual artist as well. This one isn't. At first I didn't even know he illustrated the work and did quite a bit more drawing, murals -- the writing is so remarkably visual, descriptive, ebullient. Everything in Cinnamon Shops and The Sanitorium Under the Hourglass everything is animate: pots and pans fly out of attics in the town and then the attics fly too. The lush fabrics in the father's store move in descriptions that have me resisting superlatives but really, this is so special. The father turns into a cockroach (Schulz translated Kafka into Polish), a crab, a stuffed condor; he is dead, alive, in-between. Birds take up residence in the apartment and take flight, the prose takes flight. There are themes and echoes, some of it seems so free of literary constraint but he was always completely in control. It's word-perfect. It's profound. I'm in awe of his work.

He must speak for himself now (through Madeline Levine). Some of it is so beautiful I cried. In this passage the protagonist is looking through his friend's stamp album. It's all he, or Schulz, would see of these places and it is so very -- so so very:

from Spring, part of The Sanitorium Under the Hourglass:

"In May, there were days that were pink like Egypt. In the market square radiance poured out, rippling, from every border. In the sky, the pile of summer clouds knelt, all fleecy, beneath fissures of radiance, volcanic, vividly outlined, and—Barbados, Labrador, Trinidad—everything passed into red as if seen through ruby-colored spectacles, and through those two, three pulses, through growing darkness, through the red eclipse of blood pounding against the head, the great corvette of Guyana sailed across the entire sky, exploding with all its sails. Bulging, it glided along, its canvas snorting, towed cumbersomely amid its extended lines and the clamor of the towboats, through commotions of seagulls and the red radiance of the sea. Then the immense, jumbled rigging of ropes, ladders, and poles rose up to the entire sky and expanded immensely in breadth and, booming on high with its unfurled canvas the manifold, many-storied aerial spectacle of sails, yards and clew lines opened out, while in the hatches small, agile Negro boys appeared for a moment and then scattered in that canvas labyrinth, disappearing among the signs and figures of the fantastic sky of the tropics.

"Then the scene changes, and in the sky, in the massifs of clouds, as many as three pink eclipses were coming to a climax at the same time, glowing lava was smoking, outlining with a luminous line the threatening contours of the clouds, and—Cuba, Haiti, Jamaica—the core of the world was moving into the depths, growing more and more vividly, making its way to the heart, and suddenly the pure essence of these days poured out: the murmuring oceanicity of the tropics, of archipelagic azures, of happy brooks and whirlpools, and equatorial salty monsoons. With the stamp album in my hand I read the spring. Was it not a great commentary of the times, a grammar book of its days and nights? That spring declined through all the Colombias, Costa Ricas, and Venezuelas, for what, in essence, are Mexico and Ecuador and Sierra Leone if not some kind of ingenious nostrum, some intensification of the taste of the world, some extreme, refined finality, a blind alley of aroma into which the world rushes in its quests, testing and practicing on every keyboard? The main thing, let us not forget—like Alexander the Great—is that no Mexico is the ultimate one, that it is a transitional point that the world passes by, that beyond every Mexico a new Mexico opens up, even more vivid, hypercolorful, and hyperaromatic."