What do you think?

Rate this book

576 pages, Hardcover

First published May 10, 2016

Along with a generation of idealistic reformers, Hoover was convinced that technology and logic, applied on a macro scale, were the only answer to the “great theories spun by dreamers” — social and political theories that could lead to “social and political havoc.” Engineers especially, with all their expertise in the discipline of efficiency, were naturally suited to lead a social and economic reformation. Their training, Hoover believed, placed them in “a position of disinterested service.”

“Observers of Mr. Hoover during and since his campaign are wondering how he will react to criticism, once the criticism begins,” he wrote. Already, Essary observed, Hoover had demonstrated his prickly thin skin. “He has proven himself more sensitive to censure, since his nomination, than any man in public life.”

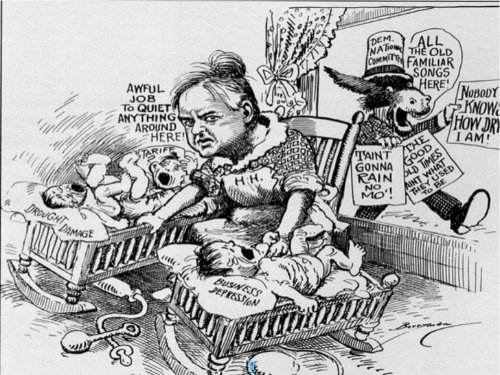

From the moment he announced as a candidate for president Herbert Hoover presented Americans with the riddle: what did it mean to place a nonpolitician — an anti-politician — in high political office? By now an answer was beginning to emerge. Hoover was striving to perform the intrinsically political task of rallying the electorate to his party standard, but there was no resonance, no sensation. The bond that connects a leader to the people might be ineffable, but now, with the country wounded and seeking direction, its absence felt uncomfortably real.

His principal addition to the formula in 1930 was to sharply curtail immigration as a threat to the domestic labor market. Just before the midterm elections Hoover announced an executive order restricting immigration to those with jobs already in hand. It was a popular measure that Hoover included in every subsequent policy statement on the Depression, though its impact was limited by the fact that, with jobs scarce, immigration was already sharply down.

By the nature of their office presidents generally believe the press corps is working against them, but there is little question that in Washington in 1932 reporters and editors had a lively antipathy for Hoover, a disdain unmatched by any successor until the next Quaker to occupy the White House — Richard Nixon, some forty years later.

Why he sought the presidency is hard to fathom. He knew he was ill-suited. He valued his privacy and was very shy. He was not a public speaker. Calvin Coolidge may be known as Silent Cal, but Hoover couldn’t have been far behind.

Hoover made a name for himself by coordinating humanitarian relief projects during and after World War I. In those and in his tenure in the Commerce Department, he displayed instinctive leadership and snap decisions. The aura of the presidency stifled his personality and made him hesitant. He believed people had exaggerated idea of him as a sort of superman, with no problem beyond his capacity. His engineering background added to that impression.

Mindboggling is his hope to be nominated to run again four years after his defeat.

Comedic are his atrocious table manners. The president was always served first. He immediately began eating, rapidly, and cleared his plate before all his guests were even served. Had his impoverished childhood led to his impulsive urgency to eat fast?

Charles Rappley’s Herbert Hoover in the White House offers a fascinating look at a president little known today. He had good ideas that were implemented by FDR, but he refused entreaties to make public statements, take a visible role in the financial crisis. That was never his style and he wasn’t going to change.