What do you think?

Rate this book

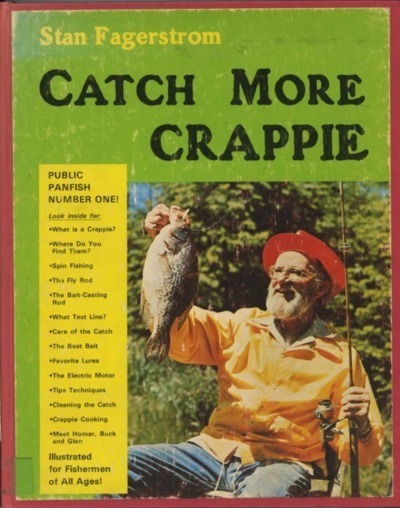

256 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1980

¡Sé que moriré en el crepúsculo! En cuál de los dos,

con cuál de los dos - ¡no seré yo quien lo decida!

¡Ah, si mi antorcha pudiera apagarse dos veces!

En el crepúsculo de la tarde y del alba - a un tiempo.

¡Con paso de danza pasé por la tierra! - ¡Hija del cielo!

¡El delantal lleno de rosas! - ¡Sin lastimar un solo brote!

¡Sé que moriré con luz crepuscular! - Dios no enviará

una noche de azores a mi alma.

Apartando con mano suave la cruz sin besos,

al cielo generoso iré por un saludo postrero.

Albores del alba - y de una sonrisa en respuesta…

¡También en el espasmo de la muerte seré - poeta!

Y - otra cosa. Si la gente hoy en día no dice «te amo», es por miedo; en primer lugar - de atarse; en segundo - de dar en exceso: de rebajar el propio precio. Por el más puro egoísmo. Los de entonces —nosotros— no decíamos «te amo» por un terror místico de matar el amor al nombrarlo, y también por la profunda certeza de que existe algo más sublime que el amor, por miedo de depreciar eso más sublime, por miedo de que una vez dicho «te amo», no se diera suficiente.

Por eso nos amaron tan poco.