Neither the old man nor Boga said more than was needed. And yet they understood each other perfectly. At dawn, they walked into this green and humming solitude that swayed with every gust of wind. Each one made his own path, stepping through the water. At times it reached their thighs, but they didn’t seem to notice. Beyond the wall of green, out towards the open sea, they heard the water murmur as it rolled tirelessly across the sandbank. The distant, sorry screaming of a limpkin. The suffocated din of a motor launch, still further off.

(p12)

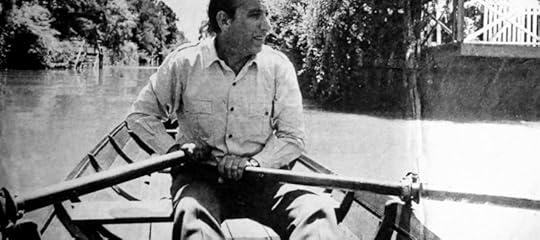

Southeaster is a curious, embracing and languid read. The story is set in the Paraná Delta just north of Buenos Aires, Argentina, and follows a man, Boga, who lives his life on the river. After his boss and companion ‘the old man’ dies, Boga leaves his work of cutting reeds and ventures forth into the Argentine Delta.

The wonder of this book is its atmosphere: while at times verging on the sentimental, the water and the sky and the landscape around Boga fill its pages. Boga remains humbled but not belittled by these giants and while author Haroldo Conti makes it clear that the masters of destiny are the elements, it is Boga’s human response to them that is where Conti’s real interest lies: when the river turns grey and Boga no longer cares what he catches, and no longer nurtures the boats he so tenderly stewards, we feel his spirits sink. Later, as he settles back into his much-longed for solitude he is noticeably satisfied and calmed by the water and sky around him.

The natural elements are big characters in this book. At the beginning of the story we are told of the sun setting:

‘this brilliant little point drew a longer line, before it sank back in the darkness and left there behind it just the briefest reddish wake’ (p52).

The reflected ‘reddish wake’ glinting on the water allows Boga – and us the reader – time to contemplate his situation, relative to the encroaching darkness around him.

Later, as the sun rises, Boga ‘saw the water in the fullness of its reach, he thought the sea had halted and turned into something solid, a sea of sand that puckered into millions of points’ (p123).

This time it is light that fills the space, with the impression that the sun achieves something just short of miraculous as it heralds the new day.

While there is a lot of this description, it isn’t tiring. Conti’s pace echoes that of a current, sweeping us along with enough stop offs and interruptions to provide human, filmic plot diversions (Conti worked on film projects with the Gente de Cine prior to writing his novels, and his attention to images, forms, colours, sounds and ‘cut’ and ‘edited’ narrative has been observed by critics).

The language and form of this book keeps us travelling along with Boga: long sentences of heavy punctuation mimic the meandering river, its repetitive currents and bend after bend of water upon water. Short words, or what Jon Lindsay Miles refers to as the "flexible bricks” of Conti's sentences in his wonderful translator's note, and a heavily rhythmic style pull you into the daily lapping reality of Boga’s existence. As the river turns cold and harsh, Conti’s sentences turn staccato:

'July was long and cruel. July killed off all hopes. A sullen irritation gripped them. The river and the sky were one, a grey and muddy wall.’ (p148)

Conti’s description of the elements is enveloping, ever changing and – through Boga – human, and there is a sense that Jon Lindsay Miles translates exactly what Conti's language was trying to do: it takes you to the river to meander along its surface, curious and on edge, but ultimately a little in awe.