Sometimes, “hard” science fiction doesn’t seem worth the effort to me. Sometimes, it seems like the author is using exposition to explain intricate systems to the reader without being concerned about the pacing of the plot. I don’t like thrillers such as Tom Clancy’s post-Patriot Games in which it seems to me that there is more attention paid to specification sheets than to human insights. Yet, The Flicker Men caught my attention for multiple reasons and I am glad it did.

First, I am fascinated by the implications of quantum theory and the plot of The Flicker Men turns on this idea. Second, I was using my understanding of quantum theory to hypothesize far-future inventions in my Traveller role-playing game and, my notes described a “flickering man” before I ever discovered this novel (We don’t treat them exactly the same, but it’s an interesting coincidence.). Third, the protagonist’s struggle has, for me and at least one of the characters in the novel, a theological debate between determinism and “free will.” That’s something I feel strongly about—especially regarding the latter which I hold true. Fourth, the protagonist’s experience unfolds a lot like one of the noir thrillers from Hard Case Crime. Except for the science, I would almost think it comparable to a Quarry novel by Max Allen Collins or one of Westlake’s darker novels. In short, The Flicker Men grabbed me and wouldn’t let me loose—even though my schedule precluded me from reading it straight through (I would have if I could have.).

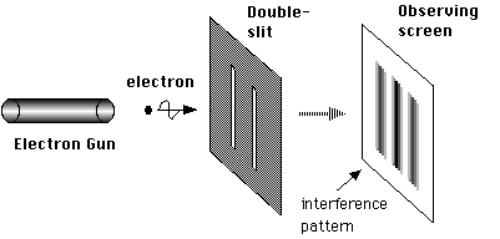

A lot of the elements in the story build from the Feynman-slit (or Young-slit) experiment, using a thermionic gun to shoot a photon stream through at two slits. The result on a monitor would be a wave-form interrupted such that an interference pattern of overlapping waves appears (p. 38). Yet, if one puts a detector at the two slits, one measures two distinct streams of phosphorescent particles. There is no interference when measuring like this (p. 39). From one reading, there is. In the real world, and before the fictional events in this novel, Feynman said of this experiment, “It has in it the heart of quantum mechanics. In truth, it contains only a mystery.” (quoted on p. 44)

Now, things become more interesting when the protagonist, Eric Argus, makes a breakthrough in his experiment. The resulting research paper garners the interest of a prominent religious evangelist. The evangelist believes he can use the research as a way to prove the existence of the human soul. While the results appear to confirm said existence, the results also reveal a frightening phenomenon. It is the latter revelation that puts Argus in a precarious position with those who are angry that the latter results were revealed. The evangelist becomes disillusioned: “Can anything in this world be truly relied upon? Even atoms are an evanescent haze—emptiness stacked upon emptiness which we have somehow willed ourselves to believe in.” (p. 126) As Argus interrogates him further and points out that his discouragement is costing his reputation, the evangelist responds, “Even fame, it seems, follows the rules of quantum mechanics. The eye of the public changes what it observes.” (p. 127)

Eventually, Argus discovers that there are those afraid of the world’s eberaxi, later defined as “errant axis” on p. 240. As quantum mechanics recognizes both the reality of the wave and the particles, Argus discovers an incongruity in the universe. “Free will in a determinant universe. Because the math was dead serious. It was only in us that it failed. The mystery wasn’t those who couldn’t collapse the waves [by their observations of Argus’ experiment]. The mystery was those who could [collapse the waves via observation.]”

To make a long story short, Argus has not just grasped, but proved the theoretical physics of “Gabriel’s horn” (aka “Torricelli’s trumpet”), the idea of a Matryoshka (aka Russian dolls) universe (p. 244). Eventually, Argus has to put the pieces together of why some can conceive of this and others cannot. And, it is a most dangerous game. Without a spoiler, let me just say that Ted Kosmatka foreshadows the conclusion perfectly. But I won’t tell you why it’s perfect, just that it’s brilliant. Indeed, I felt like The Flicker Men was brilliant through and through. I think it rivals my favorite hard science-fiction in the late James P. Hogan’s work.