The stories we tell in our attempt to make sense of the world―our myths and religion, literature and philosophy, science and art―are the comforting vehicles we use to transmit ideas of order. But beneath the quest for order lies the uneasy dread of fundamental disorder. True chaos is hard to imagine and even harder to represent. In this book, Martin Meisel considers the long effort to conjure, depict, and rationalize extreme disorder, with all the passion, excitement, and compromises the act provokes.

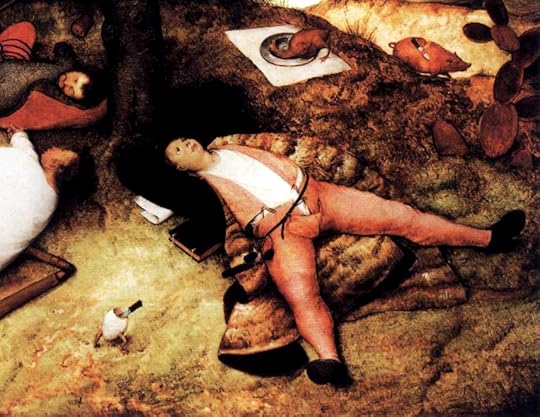

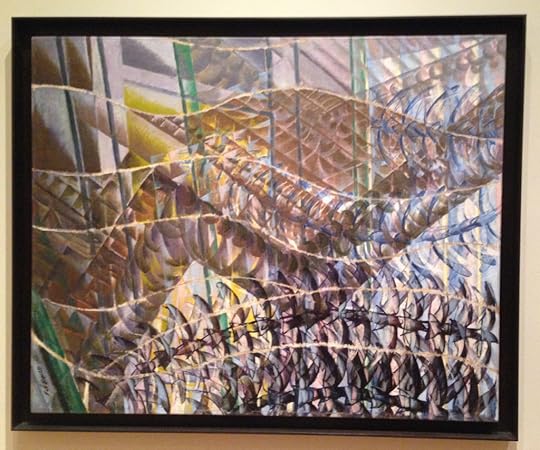

Meisel builds a rough history from major social, psychological, and cosmological turning points in the imagining of chaos. He uses examples from literature, philosophy, painting, graphic art, science, linguistics, music, and film, particularly exploring the remarkable shift in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries from conceiving of chaos as disruptive to celebrating its liberating and energizing potential. Discussions of Sophocles, Plato, Lucretius, Calderon, Milton, Haydn, Blake, Faraday, Chekhov, Faulkner, Wells, and Beckett, among others, are matched with incisive readings of art by Brueghel, Rubens, Goya, Turner, Dix, Dada, and the futurists. Meisel addresses the revolution in mapping energy and entropy and the manifold effect of thermodynamics. He then uses this chaotic frame to elaborate on purpose, mortality, meaning, and mind.