What do you think?

Rate this book

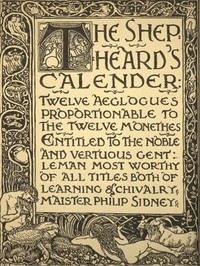

164 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1579

TO HIS BOOK.

Go, little Book! thyself present,

As child whose parent is unkent,

To him that is the President

Of Nobleness and Chivalry:

And if that Envy bark at thee,

As sure it will, for succour flee

Under the shadow of his wing.

And, asked who thee forth did bring,

A shepheard's swain, say, did thee sing,

All as his straying flock he fed:

And, when his Honour has thee read,

Crave pardon for thy hardyhed.

But, if that any ask thy name,

Say, thou wert base-begot with blame;

Forthy thereof thou takest shame.

And, when thou art past jeopardy,

Come tell me what was said of me,

And I will send more after thee.

IMMERITO.