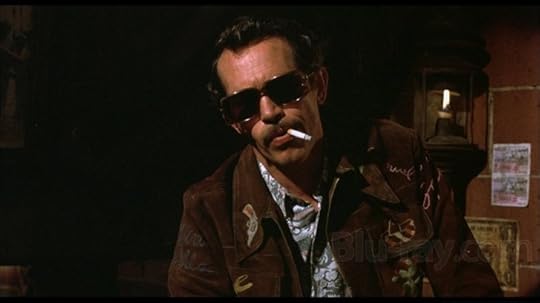

At some point during grad school, passionate as I had always been about the most rarified highfalutin literary fiction and immersed in the kind of dense prose with which the academic is obliged to grapple, I developed a passion for two American writers of popular fiction to whom I continue to retain an abiding attachment, Charles Portis and Thomas Berger. These two writers struck me then as the finest I had ever read of fiction that was fun and accessible though of great intelligence and executed with dazzling panache, and they came into my life with lessons I needed at I time when I very much needed them. They are accessible, yes, but redoubtable stylists also. They excel at novelistic structure and wrest considerable humour from the ignoble folly of human striving. Though he is still around, probably still doing his thing down in Arkansas, Portis only wrote five novels, the last of which, GRINGOS, was published in 1991. Five eminently accessible novels, fundamentally populist, may seem a modest bequest to humankind. But lo! what a reserve of riches! It did not take me long to read those five novels. Naturally. I cannot recall the exact sequence in which I read them, though I know I started with the first, NORWOOD (from 1966), and finished with GRINGOS. I cannot recall precisely when I read GRINGOS, but assume it must have been shortly before I lent my copy to my father when we were staying in a Tuscan villa in 2003 (the year I finished my MA), an event I recall quite clearly. A recovering alcoholic and drug addict, I had many encounters as a young man, including many with books and films, concerning which I do not necessarily possess the strongest recall—sometimes I possess none—and generally I reread books when that recall is especially poor, but even though I cannot remember the exact context in which I read GRINGOS, I still remembered the basic plot and all manner of incidental detail when I decided to have another go at it here over the last few days. I return to GRINGOS simply because it is one of my favourite novels of all time, Portis’s foremost achievement as far as I am concerned. It does not seem likely ol’ Charlie is gonna provide us with any more masterpieces, so I suppose revisitations will have to suffice. The writer Wells Tower has written a nice appreciation of GRINGOS, available online; it is his favourite Portis as well and a book he regularly rereads. He remarks upon a favourite line from the book, in which the narrator remarks upon how easy it is to kill a man with a double-barrel shotgun: “I wasn’t used to seeing my will so little resisted, having been in sales for so long.” (Wells Tower published an absolutely tremendous book of short fiction in 2009 and nothing substantial since. Apparently he pissed off a bunch of people at a reading in Portland last year. I hope he is okay. A man with a major gift and presumably attendant troubles.) Portis is a master of deadpan ironic gags of the kind represented by that “having been in sales so long” jewel. His deceptively simple language is always rich in overtones. TRUE GRIT was the novel that made him and almost certainly made his early retirement workable. Most people know the film versions so cannot possibly know the work for what it originally was: a stunning performance with vernacular language sublimating its own metacommentary. The Coen Brothers’ adaptation of the novel is in some ways the more objectionable of the two movie versions by virtue of the horrible things Carter Burwell’s syrupy earnest score does to the tone. Portis is smart, maniacally entertaining, and always profoundly ironic. He marches us through his mechanics with a giddy lucidity. GRINGOS is my favourite Portis both because of the basic material and the level of consolidated perfection it demonstrates in terms of technique. It is, in short, simply perfect, practically declarative as such. Telling the story of Jimmy Burns, a veteran of the Korean War originally from Louisiana who has spent a number of years eking out a half-assed living on Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, occasionally tracking down runaways and wanted persons as a side gig, GRINGOS is to an extent engaged with genre fiction, combining elements of the western and the skip-trace-style detective yarn. The novel is narrated in first person by Jimmy. Because of his own caustic call-it-like-I-see-it jive and intolerance for excessive bullshit, Jimmy has something of the quality of a Southerner Philip Marlowe to him. He used to make his living illegally salvaging relics from remote Mayan tombs et cetera, but came to realize that the practice was somewhat risky and probably ethically indefensible. He remarks on the ironic dubiousness of the whole operation: “Things had turned around, and now it was the palefaces who were being taken in with beads and trinkets.” Now he tracks down the occasional missing person and transports things for people in his truck. One of the many mantras that Jimmy shares with the reader warns that “if you have a truck your friends will drive you crazy.” There are pearls of wisdom aplenty. Writing is hard, believes Jimmy, “a form of punishment in school, and rightly so.” Approached in a bar by a man he has met before, now comparably much the worse for wear: “it seems to me you must let a haunted man make his report.” On the subject of his one-time short-term paramour Beth, a smart lady with a penchant for hooking up with poets, Jimmy notes: “Art and Mike said taking an intellectual woman into your home was like taking in a baby raccoon. They were both amusing for awhile but soon became randomly vicious and learned how to open the refrigerator.” Of course this gag tells us more about male insecurities than it does about “intellectual women.” When we first meet Jimmy Burns he is “the very picture of an American idler in Mexico” and receiving poison pen letters from an anonymous foe. There is Louise, the ninety-pound stalker, who “truly wished everyone well” and reminds Jimmy of his Methodist preacher grandfather “who included the Dionne quintuplets and the Postmaster General in his long, itemized prayers.” Louise is to wife to Rudy. Or is she? Rudy is an itinerant Ufologists come to “Mayaland” in hopes of making either contact or substantive discoveries pertaining to ancient extraterrestrial interference in earthly affairs. There are others of Rudy’s ilk about. There are also many archeologist or archeological wannabes, many of them as ridiculously puffed-up as is Rudy. Foremost among them is Dr. Richard Flandin, an elderly gentleman who has been working on his book on the Maya for many decades and who laments repeatedly and at length how he has been alternately robbed and ignored by the institution bozos. Also there are endless ragged groups of roving hippies, more specifically “real hippies, false hippies, pyramid power people, various cranks and mystics, hollow earth people, flower children and the von Däniken people” (Von Däniken was the first of the Ancient Aliens gurus). Hippies such as a disreputable crew calling themselves the Jumping Jacks, searching for the Inaccessible City of Dawn, who insist with misleading innocuousness that they have “fled the madness and found the gladness.” They are led by a malevolent guy named Dan, sporting a tattoo which betrays his having spent at least some time in the Aryan Brotherhood. In the company of the Jumping Jacks is a little red-headed girl who Jimmy will discover, having consulted the Blue Papers comprising the current roster of missing or wanted, to be a runaway named LaJoye Mishell Teeter. Rudy, the alien fanatic, will go missing. Jimmy will go off in pursuit of Rudy and LaJoye Mishell Teeter. He will be handed a .45 automatic ‘pistola' on a literal platter. There is an old man known to the locals as El Obisbo who walks around Mérida, the town where Jimmy has nominally set up shop, muttering over and over a passage from Mark about human towers coming crashing down and who may or may not turn at night into a reddish fox-faced dog generally only seen about to disappear around a corner. Jimmy Burns sees the dog right before setting off in search of Rudy and the missing girl. Omen, portent. He sets of with his friend Refugio, a first-time-out-in-the-field archeologist named Gail, and Dr. Flandin. I am only drawing a cursory sketch here, this is a book with many characters and elaborate plotting, but suffice it to say that Jimmy and Refugio pursue their quarry to Likín, a hilltop ruin over the river in Guatemala, the named derived from the Yucatec Maya word for “east” and “sunrise.” That’s right: the Inaccessible City of Dawn. Hippies have gathered there, “this flock of migrant cockatoos,” for what they believe to be the imminent end of the world, some apparently in the hopes of preventing the apocalypse by way of a sacrifice of some kind. Someone named El Mago would appear to figure in all this somewhere. Arriving at Likín: “Monkeys were screaming back and forth at one another across the river. The lunatic monkeys knew something was up.” Matters come to a head. There is a sublime coda. We find out who has been writing the poison pen letters. There are many other surprising and delightful eventualities. I have not even mentioned the chaneques, diabolic jungle elves, the bodies of two of which turn up. Might they be extraterrestrial? Well, almost certainly not, but try telling that to some people. There are, in fact, all kinds of things I haven’t mentioned. I leave them for your discovery. I have probably given you a more than adequate lay of the land. The world of GRINGOS is practically outside of time proper, almost transcending specific historical considerations. The profusion of hippies might seem to help date it, but the novel is relatively free of historical markers. One matter stands out. Jimmy Burns was at some point a teenager fighting as a Marine in Korea. He is forty-one years of age during the events that take place in the novel. Because of this, we can be fairly certain that GRINGOS, published in 1991, and otherwise not forthcoming on the subject, takes place sometime in the 70s. Portis was also a Marine in Korea. It would seem clear that he identifies with Jimmy Burns. It would seem clear that to a certain extent he hands part of his own sensibility over to this congenial loafer, lax as the man is to a certain extent, sometime half misanthrope, but always more or less good-humoured and serious about his ethics, beholden to a code (a must for heroes of genre fiction). I have said that Jimmy Burns has an intolerance for bullshit. Indeed, but only to a certain extent. He isn’t about to buy into some lunatic’s outrageous malarkey, but he realizes that the malarkey of lunatics is not always without its charms. Sure, he understands that the UFO nuts are indeed nuts. “Still, the flying saucer books were fun to read and there weren’t nearly enough of them to suit me. I liked the belligerent ones best, that took no crap off the science establishment.” Amen. Defiance should always be fun. Above all else. Turn off, tune out, go south.