What do you think?

Rate this book

352 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1927

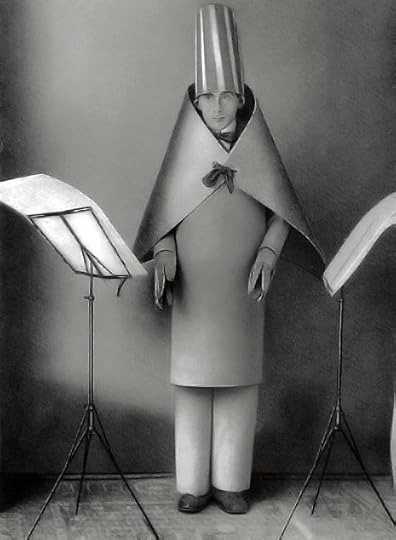

The war is based on a category error. Men have been mistaken for machines. Machines, not men, should be decimated. At some future date when only the machines march, things will be better. Then everyone will be right to rejoice when they all demolish each other.

[A]ll living art will be irrational, primitive and complex; it will speak a secret language and leave behind documents not of edification but of paradox.

jolifanto bambla o falli bambla

großiga m'pfa habla horem

egiga goramen

higo bloiko russula huju

hollaka hollala

anlogo bung

blago bung blago bung

bosso fataka

ü üü ü…

The libraries should be burned, and only the things that everyone knows by heart would survive. A great era of the legend would begin.

Even the demonic, which used to be so interesting, now has only a faint, lifeless glimmer. In the meantime all the world has become demonic. The demonic no longer differentiates the dandy from the commonplace. You just have to become a saint if you want to differentiate yourself further.

Adopt symmetries and rhythms instead of principles. Oppose world systems and acts of state by transforming them into a phrase or a brush stroke.

The distancing device is the stuff of life. Let us be thoroughly new and inventive. Let us rewrite life every day.

What we are celebrating is both buffoonery and a requiem mass.

Emmy fainted in the street. We were waiting under a streetlamp for the tram. She leaned against the wall, staggered, and gently collapsed. I got help from passers-by, and we carried her to the first-aid post in the nearby police station. Her little head was resting so peacefully and comfortably on my shoulder as I was carrying her. A strange scene in the police station: the two of us on and by the bed, and six or seven worried policemen's faces around us, giving her some water and stroking her blond hair. On the way home she smiled and said, "Why is your mouth so bitter?"