A week ago, it wasn't looking at all likely that I would finish this book in time to write this review. I felt as if I was reading the book in real time, as if by the time Morgan had been in gaol for a year, I had done my time as well So when he was condemned to seven years transportation, my heart sank, and I thought I might not finish the book until 2010.

Still, Christmas is a time for miracles, and the additional leisure time afforded by my Christmas break helped me to struggle through to the end. I'm afraid struggle is the right word because, despite the book addressing a subject in which I have a real interest (transportation to Australia), I found the level of detail tedious in the extreme.

Colleen McCullough's research for this book was, no doubt, impressive, but I think it led her into the trap of being unable to discard any of the fascinating (to her) information she had found out, whether or not it contributed to the story. There was lots of stuff I felt could have been left out and a bit of rigorous editing might have given the story a bit more pace. As it was, the story progressed by a series of frozen tableaux or lectures on 18th century life. The impression that the writer wanted to be writing not just any old story but hi-story was reinforced by footnotes explaining things that added nothing, such as the difference between Imperial and American measures. I'm not convinced people ever said things like "I am of a mind to see what is afoot", but even if they did, they don't now and I found the archaic words and constructions (vouchsafe, espouse, athwart etc) faintly embarrassing. I prefer my history to be historical rather than counterfeit contemporary fly-on-the-wall. The Fatal Shore by Robert Hughes would be (and is) my sort of book for enlightenment on the subject of transportation to Australia.

If I have to read 800+ pages about someone's life, someone like Richard Morgan would be very low on the list of lives worth the effort. Quite frankly, despite all the dramatic things that happened to him, he bored me. He bored me in the first few pages, when he dandled his son William Henry on his knee in the tavern, he bored me when he wrote his philosophical letter to Jem Thistlethwaite at the end and he bored me all the time in between. There was something horribly passive about him. Good family man who loved his wife, worshipped his children and was no doubt respectful to his elders. Yawn. Solid craftsman for whom happiness was a warm gun. Yawn. Honest citizen blowing the whistle on fraud. Yawn. Duped sap of the first sexy piece to cross his path. Yawn. I had a strong sense that Colleen McCullough made this guy up as she went along and he became what he needed to be at each part of the story. An example: I recall no mention of books in the first part of the story, yet in a later part books suddenly became the air that he breathed. There was no REAL development of Morgan as a character, he merely acquired qualities he needed just when he needed them, and these qualities were reported by others rather than derived from what went before. I reckon he was percolated through one of his own dripstones (yawn) and as lacking in charisma as filtered water is lacking in taste. I thought Morgan a very dull hero. It's people's weaknesses that make them interesting, not their strengths. I guess McCullough tried to make him more interesting by repetitive mentions of how "handsome" and by giving him rippling muscles? I wonder who will play him in the TV adaptation? I'd die of boredom with a Richard Morgan and was horrified to see from the author's afterword that she still has more to say about him. Enough! More is less. Let him rest in peace.

My biggest quarrel with the book is that it is so sanitised and romanticised. It reminded me of Swiss Family Robinson, Coral Island, Swallows and Amazons, Lost in Space. McCullough did try a bit of gritty realism, but it always looked superimposed. Whenever Morgan was getting a bit too saccharine with his polished walls, fresh vegetables or porcelain tea cups, she had someone flogged or something in an attempt to balance the books. But there is so much that seems to be missing. Despite the curious inverted snobbery that now makes it fashionable to have a convict ancestor, these were not all honest peasants who stole trifles when they were drunk or starving. There were real criminals too, who I think must have had much more of an influence on McCullough's brave new world. Apart from Kitty right at the end, no-one seemed too bothered about leaving England, no one was homesick. I'm sure that wasn't so, from what I know (a rather limited sample of one, I admit) the parting from family and friends was almost unbearable and dreams were dreamed of pardon, or of return home when a sentence was served. Funnily enough, I think there would have also been more humour, because it is one of the things that helps us to survive. The only humour here was the long-running sheep shagging joke, which wore very thin.

You will have gathered by now that I was not exactly enchanted by McCullough's tale. I thought it at least twice too long. For me, her hero was dull as ditchwater. The story was clumsily constructed, you could see the joins. No one bothered closing the curtains when the scene shifters came and went. But I must give her some credit. Her research seems to have been thorough and her writing seems competent. I expect those who enjoy this type of fiction will enjoy this very much. Unfortunately, I am not one of those and reading the book was something of a chore. The greatest impression left me by the book was relief that the reading of it was behind me and not ahead of me. Had it not been about transportation to Australia, I doubt I would have finished it at all.

* * * * *

Reviewer's Afterword

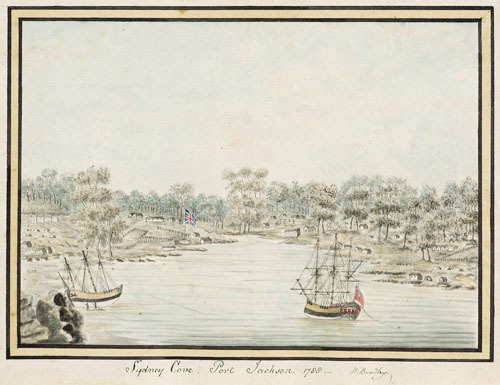

There really was a Richard Morgan on board the Alexander when the First Fleet sailed. He was tried at Gloucester, Gloucestershire on 23 March 1785 for assault and stealing a metal watch with a value of 163 shillings. He was sentenced to transportation for 7 years and left England on the Alexander aged about 25 at that time (May 1787). He had no occupation recorded. He died in 1837. He married Elizabeth Lock on 30 March 1788 though he was probably married in England and when he was sent to Norfolk Island in 1790 he lived with another woman. (I actually feel a bit more well disposed towards McCullough for weaving a complex story around these few facts.