“Some subtlety can be so voluptuous”

“I am so sorry I went to sleep. How charming of you to attribute it to drink”.

“One should rest more. Potter around. Admire one’s Chinese plates. Much love, Iris”.

I’m not quite sure I approve of this habit of publishing the letters of people who have achieved fame from writing other things but are no longer here to defend themselves against misinterpretation or criticisms of their private lives from others whose own behaviour might not always bear too much similar scrutiny, even when – as with Virginia Woolf ‘s – the letters were intended to be preserved. It’s far too profitable an industry for publishers and ‘editors’, rather unpleasantly parasitic in other words. There’s a stern instruction in one letter from Iris Murdoch to a close friend: “Destroy this and all letters. And keep your mouth shut” – an instruction evidently not carried out. On the other hand nor can I resist pouring over some of these collections, and that of Murdoch’s letters was of course irresistible because although I was an avid reader throughout almost all her literary life of everything she produced as soon as it appeared she herself remained an impenetrable mystery – high-minded moralist or mocking joker, the ultimate ivory-tower dweller or worldly sophisticate, blue-stocking or flapper, or even possibly just a very clever lunatic? A rare television appearance sometime in the ‘eighties only deepened the mystery – a quite ordinary-looking woman with a pudding-basin haircut speaking in perfectly-assured and cadenced grave sentences with the voice of complete authority. She’d waived away the taxi sent for her and set off into the London drizzle afterwards in a shabby old raincoat. This book starts to disclose the human being behind the enigma.

One doesn’t always realise the extent of one’s good fortune until well on in life. Part of mine, I see now, was to have been taken up as hardly more than a raw boy by a few people from the generation before mine, that born in the period between the two Wars, and how can the peculiar tone of that possibly be described to a younger one which appears to bear absolutely no relation to it, or indeed dismisses it entirely? Although Murdoch of course only became known in the late 1950’s and continued for another forty years, nonetheless she carried with her exactly the imprint of her early background and education, apparently largely impervious to subsequent influences though nor was she unaware of them, sometimes gently exasperated by the importunities and emotional ‘sufferings’ of others while passing with only the lightest touch over her own. It’s a great delight to resurrect that sort of understated throw-away half-gossipy English style, brittle but sometimes with deadly effect, now completely vanished, where even the War was a rather jolly occasion, the sort of things that so beset and deeply worry us now shrugged off as a bore, things of the utmost trivia raised to melodrama and perfectly outrageous behaviour was a matter of course and the subject of much amusement. As in this (1943) Mitford-ish example, so frivolously and tactfully à propos, to a male friend stranded facing the German tanks somewhere in the deserts of the Middle East: “Darling the mice have been eating your letters … I am very angry about this, chiefly because your letters are rather precious documents, but also because I am not on very good terms with the mice, and the fact that I have been careless enough to leave valuables lying around where they could get at them can be chalked up as a point to them. One day I shall declare serious war on the mice in a combined trap-poison operation. At present I am just sentimental with a fringe of annoyance. I meet them every now and then, on the stairs or underneath the gas stove, and they have such nice long tails”.

There was also, amongst the intellectual classes with their customary naivety, a great deal of intensity over the improvement of the human lot; conscientious young men rushed off in proletarian gear to interfere futilely in Spain’s internal affairs while their female counterparts in ‘rational clothing’ forget them immediately in their adulation of the heroes of Stalin’s brave new world. As a young under-graduate Murdoch joined into all that with all appropriate enthusiasm while voraciously reading a staggering quantity of books of every sort and acquiring with apparent ease a knowledge of several languages. The ‘communism’, naturally, was short-lived because she’d actually read the 19th cent Russians who understood these things far better. By the age of twenty-seven she wrote that “I wish I could be Christian. There is such worth there – and values which are real to one”. ‘Values’ and ‘religion’ remained central themes in all her writing, both philosophical and fictional, for the rest of her life – by religion, it should go without saying, she didn’t mean going to church on Sundays. Later, she grew to “hate” as she said the Labour Party for its deliberate erosion of the past, and the Communists for their insistence on a mindless uniformity and ugliness: “The Party, like the medieval church, has its tentacles right down into the remotest corners”.

One thing is decidedly clear from these letters, Murdoch was anything but a nun, although nuns appear in a very rosy light in one or two of the novels and in Nuns and Soldiers she could have been describing herself, or an aspect of herself, in the person of Anne Cavidge who relinquishes a vivacious and popular life to enter a convent to ensure a clear conscience, discovering only later what a restrictive bore (in more high-falutin’ language of course) that can be. In her time her love affairs bordered on the scandalous, and would have crossed that border had she been less adept in keeping her right hand in ignorance of the left. She was, in fact, quite a heart-breaker, even a femme fatale, through her rejection of possessiveness and espousal of what is now called polyamory; she herself referred to her own nemisism, an inescapable agent of someone else’s downfall (as in the character of Anna Quentin in Under the Net, the first novel: “her existence is one long act of disloyalty…constantly involved in secrecy and lying to conceal from each of her friends that she was so closely bound to all the others”). As a young woman she was drawn towards somewhat gloomy-sounding rumple-suited and be-spectacled pipe-smokers older or much older than herself. We won’t say anything so silly as a ‘father-fixation’ – Murdoch didn’t care for ideas of therapeutic causality (“Of course mechanics and psychoanalysis can offer us some useful generalities about ourselves. But every thing that is important and valuable and good belongs to that little piece of us which is not mechanical and no-one who is not bemused by philosophy or a youthful mood really doubts the existence of this piece”). Various other ladies, not all of them entirely benign, were passing figures of attraction too, even if ‘platonically’ (“Dearest Queen of the Night”). It means nothing to say that her romantic choices seem very odd when most people’s romantic choices are fairly incomprehensible to anyone else; the single apparently most un-rumpled man, Raymond Queneau, remained studiously out of reach in spite of a cap being thrown repeatedly at him: “if your letters to me could be slightly less impersonal I should be glad”. Elias Cannetti, unattractive in photographs, was all too available, exercising what sounds like a decidedly unwholesome influence on the impressionable Miss Murdoch; this rather sinister figure is alluded to in The Flight from the Enchanter and probably elsewhere. All was grist to the literary mill, just about every human aberration appears somewhere or other in her novels and there’s no doubt she knew what she was talking about; there’s nothing like diversity and variety in these matters for learning all about the best and worst of human nature. It was perhaps inevitable that this dangerous woman should finally marry the dullest of them all (“his chief drawback is tendency to mope like a dog in kennels when I am not there”) and whose chief virtue, perhaps, was that he hadn’t the imagination to cause trouble. I doubt that she was a woman who would seriously have wanted competition in any matrimonial setting: (“I am a homosexual in female guise, which puts me of course in a rather difficult position”, as she observed more than once, how tongue-in-cheek it’s difficult to say).

By her late forties Iris Murdoch’s reputation was so well established that she admits to often being exhausted from a gruelling round of professional commitments – lectures, public speaking not only at home but around the globe, at a stage turning out another novel every year - that the letters (because her sociable relations did not diminish) become noticeably more cursory or even slightly impatient, though without any other change of tone. Her energy was extraordinary, and of course, as ‘word processors’ had yet to be invented and she would have turned down that aid even if they had, everything was written by hand. She noticed that the world was changing, as it always is, and although for a while sympathetic to a new form of rebelliousness in the young, deplored most of it. This was particularly true in education, always her special field as a teacher at Oxford: “it is very unfair on clever or even cleverish people … not only to be forced by fashion and the few to spend time in some form of agitation but also (and this is what really gets me) to enjoy its fruits in terms of popular teachers and easy courses. … Of course young people will choose what’s easier, that their yet unexpanded imaginations and sensibilities can deal with. But the expansion is education, and that is what hurts. Yes, I am stern and sadistic towards the young, and this is what makes me a jolly good teacher”. She might have despaired had she known to what extent a student protest of the time over ‘dry academic courses’ was going to lead to a virtual elimination of a genuine education in the best sense.

It’s somewhere here that I still have a little puzzlement about Iris Murdoch. The Nice and the Good was the title of one of her cleverer novels. That the characters were “not very good at all” just adds a piquancy to the story. She herself was as nice and as good as anyone can hope for, along with being formidably intelligent, an extraordinarily rare combination. Did she ever quite realize how rare, that most of the human race is not particularly any of those things? ‘Love’ will sort everything out, she seems to be saying. Will it for the unlovable? Her affection for those she knew was, no doubt, returned, but although she knew a lot of people they were almost exclusively academically-inclined and ‘civilised’ and good manners were a necessary attribute – a lapse in that direction was properly reproved (“You have sent me a very wolfish letter full of hostility… Do not bite me in this hasty way… And don’t put me into lists. I deserve paragraphs and poems to myself”). She wrote to someone else: “I lived in a universe of perfect harmony until I was thirteen and went to boarding school and found out that the world was not composed purely of love but it was too late by then”. Even her characters meant, according to some critics, to be more or less the very embodiment of wickedness don’t seem terribly awful; if anything, it’s the tormentedly self-questioning socially-conscious ones who are more suspect for their blindness and hypocrisy. There’s one delinquent and devious youth in Henry and Cato who complains to a would-be benefactor, an aspirant priest, that “you don’t understand ordinary folks” – don’t understand because the benefactor is guiltily in love with him and conceals that under a cover of altruism of which this mauvais garçon is very well aware and exploits. In front of an image of a crucified Christ, he observes with more down-to-earth morality: “it’s a terrible thing to look at if you think of it, the nails and all that blood. If a gang done that they’d get ten years, even if the bugger survived”. In the novels almost everyone is almost permanently in a well-bred muddle, that’s part of their appeal because - intentionally or not - it’s often so comical and because their creator was such a superlative story-teller; in her philosophical writings there’s a sort of vagueness about that part of the world which is not well-bred at all, where ‘evil’ is rather conventionally summed up by totalitarianism and refugees (with whom Murdoch worked after the War) and, later, ‘environmental issues’ and so on, failings of attention to use one of her favoured expressions rather than of motivation (“There are all kinds of hard fates in the world, but all kinds of graces and alleviations come unexpectedly when one has entered into them”) . Actually, her views on ‘current affairs’, predictably liberal-ish, often seem peculiarly superficial and unreflective, as if she were agreeably accommodating to those of her correspondents rather than really caring or taking too much notice on her own account. She gave her approval to Margaret Thatcher and Indira Gandhi (with whom she’d been at school and continued occasionally to correspond with), yet there’s no comment on the latter’s sensationally gruesome end nor any apparent observation that both ladies were regarded by many as veritable monsters. Perhaps it was that she held the view that good and evil are not just always present in an unalterable balance but that each is necessary for the other. I’m not remotely denigrating Murdoch’s profound wisdom and talent, indeed reverential admiration and the greatest delight in everything she wrote is quite undimmed after this book, it’s just that she wasn’t for nothing the greatest proponent in our times of a genuinely ‘aristocratic’ Platonism and had no truck with kitchen-sink literature (“such tosh”; rather oddly she had no liking either for Flaubert and only reservedly for George Elliot, her favourite writers were Dickens and Proust and Dostoievsky). There was a genuine sympathy for the underdog but not a preference for his company. Perhaps that had something to do with her aversion to anything ‘psychological’, but perhaps it also accounts for why many novel-readers find her incomprehensible or even insufferable (judging by some of the comments in places like this): though accurately and meticulously observed and drawn the characters could seem to bear little relation to anyone one knows, usually without visible means of support but quite untroubled by financial embarrassments or practical domestic irritations, breaking even if they’re rather stupid into improbably intellectual dialogues at the drop of a hat, usually existing or claiming to in a state of high moral consciousness whether they live up to it or not and in sharp contrast to such other great writers as Proust or Balzac or George Elliot or Marguerite Yourcenar for example, whose characters are almost alarmingly recognizable and have a sort of extra hard fierceness and ‘realism’ about them. Murdoch herself offers a very insightful observation, that the main difficulty for the novelist is to keep a balance between real people and images; the main difficulty for herself she must have meant, since all novelists of this calibre are unique. Philosophy of course, or Murdoch’s brilliantly-inspiring variety of musings on how to be good without god and in which she was equally prolific even though she says more than once that philosophy is “too difficult” for her, deals only in imagery, and the real difficulty – since no other person has equally combined the two interests so formidably – is that they don’t exactly mix (though it could as well be asked, what is a ‘novel’ anyway, or what is ‘philosophy’ come to that). A certain perplexity arises from the suspicion that although Murdoch had a strong sense of humour she had little or no sense of irony any more than she had – even if sounds rather rude to say it – much of a sense of ‘good taste’ (in material objects), never developing in that respect beyond a conventional school-girl. Or perhaps just a reluctance to use those - if one likes - frivolous senses for reasons of preserving another one; she very much disliked ‘cruelty’ and it would be tempting to say that she wilfully preserved a sort of innocence which is more Oriental than ordinarily Western (she knew a lot about Oriental religions and was much taken with them). Amusing or not according to taste, her characterizations are in no way satirical or in jest, they are vehicles for exploring moral dilemmas or even abstractions – dilemmas to which the baser and greater part of humanity pays little or no heed. Since her death these disparities have become even more pronounced, the last remnants of the world she inhabited so little time ago no longer existing. A pity, since as she said the Socratic Dialogues were not intended to provide answers but to induce thought about the questions, and Plato in spite of himself was one of the few great poets.

There are very charming qualities in these letters. They’re unfailingly kind and tactfully polite – ‘compassionate’ and ‘understanding’ to use currently over-worked and therefore largely degraded language – while not conceding an inch in false flattery or compromise of principles, nor above gently chiding the correspondent for lack of the same. To the often tiresomely exigent and generally second-rate Brigid Brophy: “To hell with these bloody metaphors … I am not a great writer. Neither are you. I have never of course really told you what I think of your work, though what I have said is truthful. In fact I don’t think critically in detail about what you write. I love it as an emanation of you and admire what is patently admirable in it.” Or as an aside to a young admirer and temporary paramour to whom she’d been generous in reply to a gushy thank-you note: “That meal was lunch by the way. We are not U enough to call it luncheon”. By never picking quarrels and giving her friends the benefit of the doubt she kept most of them for most of her life or theirs. Also, the letters are very attractively self-effacing, in “good form”, the casual reader would never know that the writer was so eminent and famous; there’s an occasional passing reference to feeling a bit drained after finishing another book, nothing else, no discussion of them or any fishing for praise and a deliberate repulsion of any attempts at ‘interpretation’. (I wonder if her friends actually read her books or liked them if they did?) Above all is the sparkling sense of immediacy, that they’re just hastily written conversations, not composed ‘for the record’. Reading them it’s not so difficult to believe that writing more novels than any other author caused her no great difficulty, they’d already been completely worked out in her head in the course of doing other things so that putting the words down was nothing more than taking dictation, and that’s a truly phenomenal talent.

Presumably these letters would be of little or no interest to other than Murdoch admirers already conversant with her work yet in them we see her practising what she preached, a rare accomplishment in itself and from which there are many lessons to be learned by everyone. Regrettably, I fear insofar as she’s remembered at all in the wider public consciousness, thanks to the self-seeking diligence of memoirists and film-makers, it’s as a helpless and rambling old woman and it can only be hoped that her shade finally sees the irony of that.

BOTW

BOTW http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b06pssb5

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b06pssb5 1: This episode focuses on her years as an Oxford undergraduate when she was full of hope and political idealism.

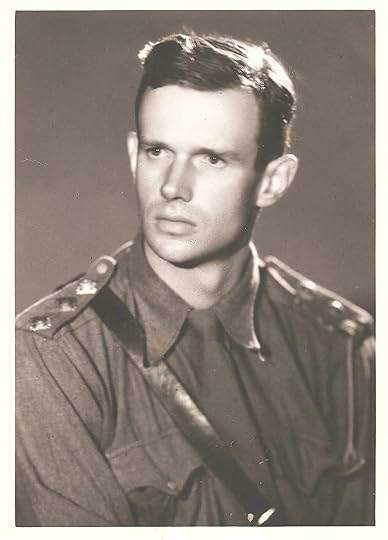

1: This episode focuses on her years as an Oxford undergraduate when she was full of hope and political idealism. 2: In this episode, which embraces the years 1942-1944 when Murdoch was working at the Treasury, the letters to her Oxford friend, Frank Thompson, are particularly poignant.

2: In this episode, which embraces the years 1942-1944 when Murdoch was working at the Treasury, the letters to her Oxford friend, Frank Thompson, are particularly poignant. 3: Iris Murdoch had not seen David Hicks since 1938 when they were both at Oxford, but she continued to write until, in November 1945, they finally met up again. This time in London and with dramatic consequences.

3: Iris Murdoch had not seen David Hicks since 1938 when they were both at Oxford, but she continued to write until, in November 1945, they finally met up again. This time in London and with dramatic consequences. 4: For 30 years, the French writer Raymond Queneau and Iris Murdoch exchanged letters. The Frenchman was her muse and, in Murdoch's chaotic private life, perhaps the one constant.

4: For 30 years, the French writer Raymond Queneau and Iris Murdoch exchanged letters. The Frenchman was her muse and, in Murdoch's chaotic private life, perhaps the one constant. 5: Iris Murdoch and Brigid Brophy had an intimate friendship for many years, but Murdoch's letters reveal how volatile the relationship could be.

5: Iris Murdoch and Brigid Brophy had an intimate friendship for many years, but Murdoch's letters reveal how volatile the relationship could be. 'Frank Thompson is better known in Britain as brother of the historian EP Thompson, but in Bulgaria he is a national hero. Attached during the second world war to Special Operations Executive (SOE), he was parachuted into the Balkans to work with Bulgarian partisans; after two weeks of eating salted leaves and live wood-snails, he was captured, tortured and murdered by the Nazis.'Source

'Frank Thompson is better known in Britain as brother of the historian EP Thompson, but in Bulgaria he is a national hero. Attached during the second world war to Special Operations Executive (SOE), he was parachuted into the Balkans to work with Bulgarian partisans; after two weeks of eating salted leaves and live wood-snails, he was captured, tortured and murdered by the Nazis.'Source Raymond Queneau a French novelist, poet, and co-founder of Oulipo (Ouvroir de littérature potentielle), notable for his wit and cynical humour.

Raymond Queneau a French novelist, poet, and co-founder of Oulipo (Ouvroir de littérature potentielle), notable for his wit and cynical humour.