What do you think?

Rate this book

256 pages, Hardcover

First published May 3, 2016

This book is about the lives of young people who finished high school and then found themselves in a war – in a forgotten little corner of a forgotten little war, but one that has nonetheless reverberated in our lives and in the life of our country and the world since it ended one night in the first spring of the new century. Anyone looking for the origins of the Middle East of today would do well to look closely at these events.

Israel had gone into Lebanon all those years ago because of Palestinian guerrillas attacking across the border, but the Palestinians were long gone. The enemy had changed, and now it was Hezbollah. This group was Lebanese but created by Iran, the rising regional power, with the help of Syria, which controlled Lebanon. Hezbollah took orders from the dictatorship in Syria and from the clerics running Iran. Hezbollah was supposedly fighting to get us out of Lebanon, but Hezbollah leaders made clear later that they had rebuffed Israeli offers for a negotiated withdrawal. They didn't want us to leave; they wanted to push us out, which is not the same thing. By killing soldiers in the security zone they didn't convince Israelis to leave but rather that the security zone was necessary, and we dug in deeper and deeper to justify what we had already lost. This changed only with the helicopter crash, which had nothing to do with Hezbollah. Subsequent events show that they hoped to use their war against us to become the dominant power in Lebanon, which they went on to do with considerable skill. Their war seems to have always been as much for their country as it was against ours.

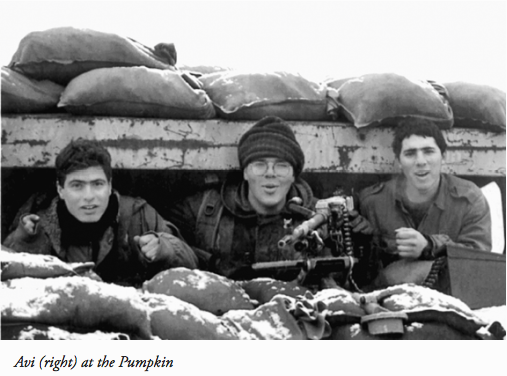

On the hill we had been at the start of something: of a new era in which conflict surges, shifts, or fades but doesn't end, in which the most you can hope for is not peace, or the arrival of a better age, but only to remain safe as long as possible. None of us could have seen how the region would be seized by its own violence – the way Syria, a short drive from the outpost, would be devoured, and Iraq, and Libya, and Yemen, and much of the Islamic world around us. The outpost was the beginning. Its end was still the beginning. My return as a civilian was still the beginning. The present day might still be the beginning. The Pumpkin is gone, but nothing is over.

When [the regional conflicts in Israel’s recent past failed to produce the expected outcome] something interesting occurred. People in Israel didn’t despair, as our enemies hoped. Instead they stopped paying attention. What would we gain from looking to our neighbors? Only heartbreak, and a slow descent after them into the pit. No, we would turn our back on them and look elsewhere, to the film festivals of Berlin and Copenhagen or the tech parks of California. Our happiness would no longer depend on the moods of people who wish us ill, and their happiness wouldn’t concern us more than ours concerns them. Something important in the mind of the country -- an old utopian optimism -- was laid to rest. At the same time we were liberated, most of us, from the curse of existing as characters in a mythic drama, from the hallucination that our lives are enactments of the great moral problems of humanity, that people in Israel are anything other than people, hauling their biology from home to work and trying to eke out the usual human pleasures in an unfortunate region and an abnormal history.

[...] Israel isn’t a place of slogans anymore, certainly not the Zionist classics “If you will it, it is no dream,” or “We have come to the Land to build and be rebuilt.” But if one were needed now, why not recall Harel’s laconic explanation of how he went back to the army after the funerals of every single member of his platoon but him? I don’t think we could do better than “On the bus.” (188-189)