It's fate, isn't it? One moment we're in the sunlight, and the next every dark cloud in Christendom is pissing all over us.

Uhtred of Bebbanburg is getting old and cranky. Ten years of relative peace in the kingdoms of Wessex and Mercia don't do much to improve his temper, despite having good sons, a young wife, lands and liegemen and a reputation as the fiercest warrior in all the Saxon lands. The hot-blooded Uhtred digs his own grave when he accidentally kills one of the local Bishops, and finds himself an outcast, a renegade, a pauper - something that actually happens in every single installment of Bernard Cornwell Saxon Chronicles. His hero is bred for war and not for peace, and the tenth century England provides ample opportunity to indulge his passions.

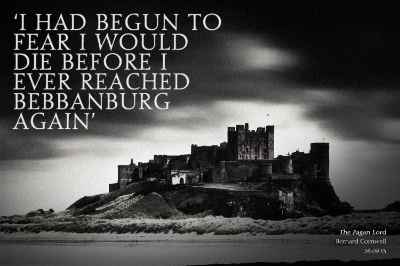

Speaking of passions, Uhtred at the start of his fifth decade is a bit slower in his drinking and skirt chasing, but his hatred of Christian duplicity is as strong as ever, and his readiness for adventure is unchanged over the decades. In every disaster thrown at him, Uhtred finds an opportunity to wipe the slate clean and start life anew. In this episode he goes back to his roots - to the quest of regaining control of his father's castle at Bebbanburg and to his love for raiding the sea lanes:

I love the whale'a path, the wind flecking the world with blown spray, the dip of a ship's prow into a swelling wave and the explosion of white and the spatter of saltwater on sail and timbers, and the green heart of a great sea rolling behind the ship, rearing up, threatening, the broken crest curling, and then the stern lifts to the surge and the hull lunges forward and the sea seethes along the strakes as the wave roars past. I love the birds skimming the grey water, the wind as friend and as enemy, the oars lifting and falling. I love the sea. I have lived long and I know the turbulence of life, the cares that weigh a man's soul and the sorrows that turn the hair white and the heart heavy, but all those are lifted along the whale's path. Only at sea is a man truly free.

From the very first book of the Saxon series I was captivated not only by the historical recreation of a turbulent period in history, but also by the spiritual struggle for men's souls between the Pagans and the Christians. The author's sympathies are clearly skewed towards the warrior culture of the Norsemen, but Cornwell is a subtle enough writer who doesn't shy away from the seeing the good points of the priesthood and the disastrous results of total war. In the tenth century, the country that was to become England was slowly coming under the control of the Church, but this process was only made possible by the military developments of walled cities (burhs) and by the valiant efforts of the despised professional killers like Uhtred. Yet, looking at the centuries that preceded and at the centuries that followed the rule of Alfred the Great, the reader is reminded that these particular times came to be known in history as the Dark Ages:

The remnants of Rome always make me sad, simply because they are proof that we slide inexorably towards the darkness. Once there was light falling on marbled magnificence, and now we trudge through the mud.

Both the Church and the Norse Gods promise reincarnation and life eternal for their chosen ones, but while one creed advocates meekness and submission, the other rewards the fighting spirit and the joy of life. My favorite passage is a fragment of the Norse Sagas that acknoledges the terrible Fate the Gods have decreed for mankind (through the threads woven by the Norns) without advocating resignation.

So Uror, Veroandi and Skuld would decide our fate. They are not kindly women, indeed they are monstrous and malevolent hags, and Skuld's shears are sharp. When those blades cut they feed the well of Uror that lies beside the world tree, and the well gives the water that keeps Yggdrasil alive, and if Yggdrasil dies then the world dies, and so the well must be kept filled and for that there must be tears. We cry so the world can live.

>><<>><<>><<

The Pagan Lord may be a late installment in the Saxon Chronicles, but for me it is one of the best episodes, mostly for its extensive action sequences : a storm at sea, an attack against a fortified castle, the sacking of a major fortress, the glorious final battle. Uhtred can be found each and every time in the midst of the carnage, where he rules over the battlefield like a true Lord of War:

A battle is the shield wall. It's smelling your enemy's breath while he tries to disembowel you with an axe, it's blood and shit and screams and pain and terror. It's trampling in your friend's guts as enemies butcher them. It's men clenching their teeth so hard they shatter them. Have you ever been in battle?

Cornwell has taken some liberties with the source material, an unavoidable decision, given the scarcity of historical detail about the people and the battles that shaped modern England. But his books are the kind of novels that I would have loved to learn my history from in my school days, same as I used Alexandre Dumas or Victor Hugo to get interested in French history. I know the series is unfinished and that it is in danger of becoming drawn out and unfocused, but I will keep buying them Uhtred yarns as long as Cornwell continues to write them.