What do you think?

Rate this book

520 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1938

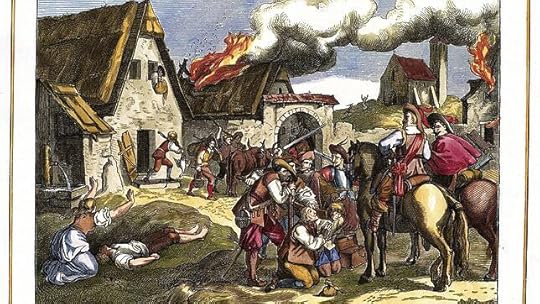

At Calw the pastor saw a woman gnawing the raw flesh of a dead horse on which a hungry dog and some ravens were also feeding. In Alsace the bodies of criminals were torn from the gallows and devoured; in Zweibrücken a woman confessed to having eaten her child. Acorns, goats' skins, grass, were all cooked in Alsace; cats, dogs, and rats were sold in the market at Worms. In Fulda and Coburg and near Frankfort and the great refugee camp, men went in terror of being killed and eaten by those maddened by hunger. Near Worms hands and feet were found half cooked in a gipsies' cauldron. Not far from Wertheim human bones were discovered in a pit, fresh, fleshless, sucked to the marrow.

A new emotional urge had to be found to fill the place of spiritual conviction; national feeling welled up to fill the gap. […] The terms Protestant and Catholic gradually lose their vigour; the terms German, Frenchman, Swede, assume a gathering menace.

"The peace of Westphalia was like most peace treaties, a rearrangement of the European map ready for the next war. ... The war solved no problem, its effects both immediate and indirect were either negative or disastrous. Morally subversive, economically destructive, socially degrading, confused in its causes, devious in its course, futile in its results, it is the outstanding example in European history of meaningless conflict."Indeed, it was like all wars.

While increasing preoccupation with natural science had opened up a new philosophy to the educated world, the tragic results of applied religion had discredited the Churches as the directors of the State. It was not that faith had grown less among the masses; even among the educated and the speculative it still maintained a rigid hold, but it had grown more personal, had become essentially a matter between the individual and his Creator

Inevitably the spiritual force went out of public life, while religion ran to seed amid private conjecture, and priests and pastors, gradually abandoned by the State, fought a losing battle against philosophy and science. While Germany suffered in sterility, the new dawn rose over Europe, irradiating from Italy over France, England, and the North. Descartes and Hobbes were already writing, the discoveries of Galileo, Kepler, Harvey, had taken their places as part of the accepted stock of common knowledge. Everywhere lip-service to reason replaced the blind impulses of the spirit.

A new emotional urge had to be found to fill the place of spiritual conviction; national feeling welled up to fill the gap.The absolutist and the representative principle were losing the support of religion; they gained that of nationalism. That is the key to the development of the war in its latter period. The terms Protestant and Catholic gradually lose their vigour, the terms German, Frenchman, Swede, assume a gathering menace. The struggle between the Hapsburg dynasty and its opponents ceased to be the conflict of two religions and became the struggle of nations for a balance of power. A new standard of right and wrong came into the political world. The old morality cracked when the Pope set himself up in opposition to the Hapsburg Crusade, and when Catholic France, under the guidance of her great Cardinal, gave subsidies to Protestant Sweden. Insensibly and rapidly after that, the Cross gave place to the flag, and the ‘Sancta Maria’ cry of the White Hill to the ‘Viva España’ of Nördlingen.

At Calw the pastor saw a woman gnawing on the raw flesh of a dead horse on which a hungry dog and some ravens were also feeding. In Alsace the bodies of criminals were torn from the gallows and devoured; in the whole Rhineland they watched the graveyards against marauders who sold the flesh of the newly buried for food; at Zweibrucken a woman confessed to having eaten her child. Acorns, goats' skins, grass, were all cooked in Alsace; cats, dogs, and rats were sold in the market at Worms. In Fulda and Coburg and near Frankfurt and the great refugee camp, men went in terror of being killed and eaten by those maddened by hunger...