What do you think?

Rate this book

189 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1967

At seven-twenty, the engines of the sixty helicopters started simultaneously, with a thunderous roar and a storm of dust. After idling his engine for three minutes on the airstrip, our pilot raised his right hand in the air, forming a circle with the forefinger and thumb, to show that he hoped everything would proceed perfectly from then on. The helicopter rose slowly from the airstrip right after the helicopter in front of it had risen. The pilot’s gesture was the only indication that the seven men were on their way to something more than a nine-o’clock job. Rising, one after another, in two parallel lines of thirty, the fleet of sixty helicopters circled the base twice, gaining altitude and tightening their formation, as they did so, until each machine was not more than twenty yards from the one immediately in front of it. Then the fleet, straightening out the two lines, headed south, toward Ben Suc.

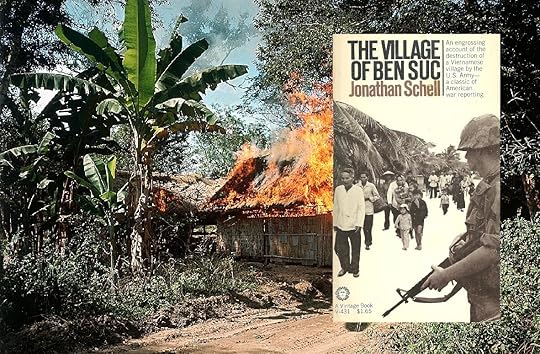

When the demolition teams withdrew, they had flattened the village, but the original plan for the demolition had not yet run its course. Faithful to the initial design, Air Force jets sent their bombs down on the deserted ruins, scorching again the burned foundations of the houses and pulverizing for a second time the heaps of rubble, in the hope of collapsing tunnels too deep and well hidden for the bulldozers to crush – as though, having once decided to destroy it, we were now bent on annihilating every possible indication that the village of Ben Suc had ever existed.