What do you think?

Rate this book

400 pages, Paperback

First published January 5, 2016

BOTW

BOTW http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b06zqn0x

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b06zqn0x In the first episode, we meet seventeen year old Guled, as he struggles to survive on the outskirts of Mogadishu. He still tries to attend school as well as to earn a living, but the al-Shabaab militias are closing in.

In the first episode, we meet seventeen year old Guled, as he struggles to survive on the outskirts of Mogadishu. He still tries to attend school as well as to earn a living, but the al-Shabaab militias are closing in. 2/5: After the deaths of his parents, Guled has been struggling to survive, together with his sister, in a makeshift camp on the edge of Mogadishu. But when al-Shabaab force him from the classroom he fears not just for his own life but also worries about his new bride, Maryam.

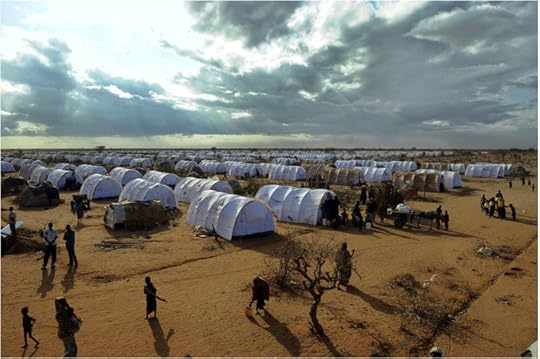

2/5: After the deaths of his parents, Guled has been struggling to survive, together with his sister, in a makeshift camp on the edge of Mogadishu. But when al-Shabaab force him from the classroom he fears not just for his own life but also worries about his new bride, Maryam. 3/5: Nisho has only ever known life in Ifo - one of the camps in Dadaab. His job as a porter in the market enables him to scrape together a little extra to help his mother, whose failing mental health fills him with anxiety. But from his position, almost at the bottom of the pile, he harbours ambitions for the future.

3/5: Nisho has only ever known life in Ifo - one of the camps in Dadaab. His job as a porter in the market enables him to scrape together a little extra to help his mother, whose failing mental health fills him with anxiety. But from his position, almost at the bottom of the pile, he harbours ambitions for the future. 4/5: The camp is a semi-permanent home (the inhabitants are not allowed to leave without permission) to people fleeing conflicts from all over Africa. And it's far from exclusive to people of one faith. So when Monday, a young Catholic man from Sudan. falls for the beautiful Muna - a Somali Muslim - tensions are bound to ensue.

4/5: The camp is a semi-permanent home (the inhabitants are not allowed to leave without permission) to people fleeing conflicts from all over Africa. And it's far from exclusive to people of one faith. So when Monday, a young Catholic man from Sudan. falls for the beautiful Muna - a Somali Muslim - tensions are bound to ensue. 5/5: Monday and Muna find their child, Christine, is being attacked by embittered Somali clan members. Guled threatens to make the long journey to Italy, and in Washington Ben Rawlence tries in vain to explain the nuances of Dadaab life to the National Security Council.

5/5: Monday and Muna find their child, Christine, is being attacked by embittered Somali clan members. Guled threatens to make the long journey to Italy, and in Washington Ben Rawlence tries in vain to explain the nuances of Dadaab life to the National Security Council.