What do you think?

Rate this book

Winner, 2016 National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism

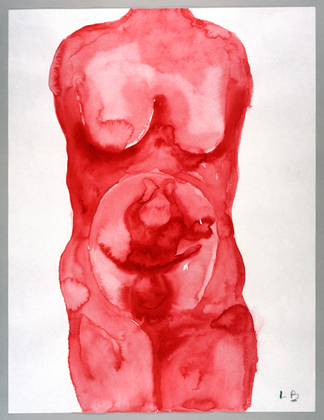

Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts is a genre-bending memoir, a work of ‘autotheory’ offering fresh, fierce and timely thinking about desire, identity and the limitations and possibilities of love and language. At its centre is a romance: the story of the author’s relationship with the artist Harry Dodge. This story, which includes the author’s account of falling in love with Dodge, who is fluidly gendered, as well as her journey to and through a pregnancy, is an intimate portrayal of the complexities and joys of (queer) family making.

Writing in the spirit of public intellectuals such as Susan Sontag and Roland Barthes, Nelson binds her personal experience to a rigorous exploration of what iconic theorists have said about sexuality, gender, and the vexed institutions of marriage and child-rearing. Nelson’s insistence on radical individual freedom and the value of caretaking becomes the rallying cry for this thoughtful, unabashed, uncompromising book.

Maggie Nelson is a poet, a critic, and the author of several nonfiction books, including The Red Parts, The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning, Bluets, and Jane: A Murder. She teaches in the School of Critical Studies at CalArts and lives in Los Angeles, California.

‘A superb exploration of the risk and the excitement of change…An exceptional portrait both of a romantic partnership and of the collaboration between Nelson’s mind and heart.’ New Yorker

‘Maggie Nelson slays entrenched notions of gender, marriage and sexuality with lyricism, intellectual brass and soul-ringing honesty.’ Vanity Fair

‘A magnificent achievement of thought, care and art.’ Los Angeles Times

‘Nelson’s writing is fluid—to read her story is to drift dreamily among her thoughts…She masterfully analyzes the way we talk about sex and gender.’ Huffington Post

‘One of the most intelligent, generous and moving books of the year.’ STARRED review Publishers Weekly

‘A book that will challenge readers as much as the author has challenged herself.’ STARRED review Kirkus Reviews

‘So much writing about motherhood makes the world seem smaller after the child arrives, more circumscribed, as if in tacit fealty to the larger cultural assumptions about moms and domesticity; Nelson’s book does the opposite.’ New York Times Book Review

183 pages, Kindle Edition

First published May 5, 2015

October, 2007. The Santa Ana winds are shredding the bark off the eucalyptus trees in long white stripes. A friend and I risk the widowmakers by having lunch outside, during which she suggests I tattoo the words HARD TO GET across my knuckles, as a reminder of this pose’s possible fruits. Instead the words I love you come tumbling out of my mouth in an incantation the first time you fuck me in the ass, my face smashed against the cement floor of your dank and charming bachelor pad. You had Molloy by your bedside and a stack of cocks in a shadowy unused shower stall. Does it get any better? What’s your pleasure? you asked, then stuck around for an answer.

Before we met, I had spent a lifetime devoted to Wittgenstein’s idea that the inexpressible is contained - inexpressibly! - in the expressed. This idea gets less air time than his more reverential Whereof one cannot speak thereof one must be silent, but it is, I think, the deeper idea. Its paradox is, quite literally, why I write, or how I feel able to keep writing

A few years ago, she told me the story of a subsequent feminist theory class that threw a kind of coup. They wanted - in keeping with a long feminist tradition - a different kind of pedagogy than that of sitting around a table with an instructor. They were frustrated by the poststructuralist ethos of her teaching, they were tired of dismantling identities, tired of hearing that the most resistance one could muster in a Foucauldian universe was to work the trap one is inevitably in. So they staged a walkout and held class in a private setting, to which they invited Christina as a guest. When people arrived, Christina told me, a student handed everyone an index card and asked them to write ‘how they identified’ on it, then pin it to their lapel.

There are people out there who get annoyed at the story that Djuna Barnes, rather than identify as a lesbian, preferred to say that she “just loved Thelma.” Gertrude Stein reputedly made similar claims, albeit not in those exact terms, about Alice. I get why it’s politically maddening, but I’ve also always thought it a little romantic - the romance of letting an individual experience of desire take precedence over a categorical one.

Shame-spot: being someone who spoke freely, copiously, and passionately in high school, then arriving in college and realizing I was in danger of becoming one of those people who makes everyone else roll their eyes: there she goes again. It took some time and trouble, but eventually I learned to stop talking, to be (impersonate, really) an observer. This impersonation led me to write an enormous amount in the margins of my notebooks - marginalia I would later mine to make poems.

How to explain - “trans” may work well enough as shorthand, but the quickly developing mainstream narrative it evokes (“born in the wrong body,” necessitating an orthopedic pilgrimage between two fixed destinations) is useless for some - but partially, or even profoundly, useful for others? That for some, “transitioning” may mean leaving one gender entirely behind, while for others - like Harry, who is happy to identify as a butch on T - it doesn’t? I’m not on my way anywhere, Harry sometimes tells inquirers. How to explain, in a culture frantic for resolution, that sometimes the shit stays messy?

come to my blog!

come to my blog!

"A day or two after my love pronouncement, now feral with vulnerability, I sent you the passage from Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes in which Barthes describes how the subject who utters the phrase "I love you" is like "the Argonaut renewing his ship during its voyage without changing its name." Just as the Argo's parts may be replaced over time but the boat is still called the Argo, whenever the lover utters the phrase "I love you," its meaning must be renewed by each use, as "the very task of love and of language is to give to one and the same phrase inflections which will be forever anew."This book, while seemingly brief, goes deep - into the personal history, into the research. It takes longer to read than one might expect, and even longer to process.