“[Tom Ripley] had certainly overstayed his welcome at Dickie’s in Mongibello in his callow youth…Tom had come from America, or rather had been sent by Dickie’s father, Herbert Greenleaf, to bring Dickie back home. It had been a classic situation. Dickie hadn’t wanted to go back to the United States. And Tom’s naivete at that time, was something that now made him cringe. The things he had had to learn! And then – well, Tom Ripley had stayed in Europe. He had learned a bit. After all he had some money – Dickie’s…”

- Patricia Highsmith, Ripley Under Ground

In the 1860s, the author Horatio Alger wrote a number of successful young adult novels – most famously Ragged Dick – about impoverished lads rising from the moral and economic bankruptcy of the streets to achieve bourgeoise respectability. This up-by-the-bootstraps ideal has since become woven into the fabric of American belief, the idea that any ambitious person, through a combination of clean living and hard work, can achieve financial and social success.

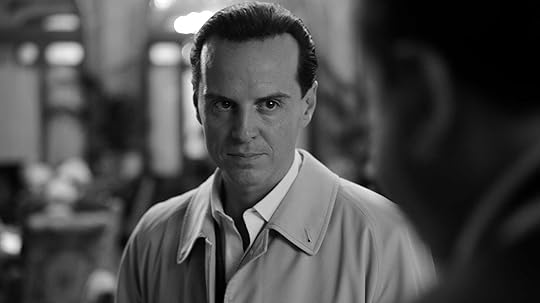

It occurred to me, as I was reading Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley Under Ground, that protagonist Tom Ripley is sort of a funhouse mirror version of one of Alger’s scrappy strivers. Like Alger’s most famous character, Ripley is an orphan intent on remaking himself in a new, better image. He is cheerful in the face of adversity, and zealously focused on achieving his goals.

Of course, there the comparisons end. While Ragged Dick utilized honest employment and the occasional good deed for wealthy men to better his position, Ripley’s methods are a bit more – well, let’s say they’re a bit more dubious.

It is that dubiousness – this unflinching willingness to do whatever it takes – that makes Ripley so much more interesting than Alger’s creations, and one of the great inventions in all of fiction.

***

When I finished The Talented Mr. Ripley, the first in Highsmith’s Ripley series, I was entirely satisfied. I did not feel the need for more. The story was perfectly self-contained, and though it left loose threads, it felt natural, since the novel itself dwells confidently in ambiguities. I had only two reasons for picking up Ripley Under Ground, the second entry: first, I had already purchased it, while under the influence of wine; and second, Ripley is an utterly fascinating character, a man who you can’t help loving, despite his methods. He’s a bad dude who needs to be stopped, yet I was cheering for him every dreadful step of the way.

Though it is the sequel to The Talented Mr. Ripley, Ripley Under Ground is not a direct follow-up. Instead, it picks up around six years after the events of the prior book. I found this a little disorienting, since a lot has changed, and Highsmith essentially begins the novel in media res, with the plot already in motion.

In brief, Tom is living in France, in a lovely home in the countryside. He is also neck deep in a complex art forging scheme, the details of which are only gradually revealed. A nosy American is threatening to expose the fraud, and though Tom is not really in it for the money – it’s more about the laughs – he gears up to protect himself and his friends. As if that wasn’t enough, a cousin of Dickie Greenleaf soon comes a calling.

More importantly, Tom’s married!

Yes, the man whose sexuality was so acutely studied in The Talented Mr. Ripley has married a French pharmaceutical heiress named Heloise. Highsmith, perhaps tweaking the audience, still toys with our ability to label Tom with regard to his orientation. In her carefully calibrated – that is, vague – description of how he came to be joined in matrimony, she provides fodder for debate.

For me, Tom’s sex life is not nearly as interesting as his everyday interactions with Heloise, because she gives us another access point with which to view and judge Tom Ripley. Despite whatever reservations Tom might have between the sheets, he seems to genuinely like Heloise, even depend on her. There is also the possibility that Tom – a seeming stone-sociopath – might even love her. Beyond that, Highsmith tantalizes with the prospect that Heloise might be Tom’s perfect mate, in a very specific way.

I liked Ripley Under Ground very much. It was exceptionally fast-paced, twisty, and occasionally gave me sweaty palms. Highsmith, who spent much of her life abroad, has a keen sense of place, and after a year in coronavirus-induced hiding, it was extremely pleasant to go on a vacation of sorts, following Tom as he travels about France, London, and Austria. There were times I felt like I was with him, sitting at a sidewalk café, drinking coffee out of a dainty cup, an unopened book of poems resting next to me, plotting the destruction of my enemies without my pulse every missing a beat.

That said, this was not as good as The Talented Mr. Ripley. Though I never got lost, the byzantine nature of the proceedings, as well as Tom’s reactions to certain events, really strained credulity. Tom’s ability to succeed often felt less a function of his skills, and more a function of English and French police inspectors being as credulous and unassuming as small children. Furthermore, Ripley Under Ground repeats a lot of the prior novel’s tricks. Tom has a nasty habit of responding to most of life’s roadblocks with a blunt aggressiveness that gets wearisome. His decision to attack every Gordian knot with Occam’s freshly-sharpened razor gets predictable. Instead of having Tom adapt his responses, Highsmith instead doubles down on gruesomeness. This leads to a grim scene of evidence disposal that is narrated with such an even-keeled tone that it took me a minute to realize how genuinely funny – in a sick way – Highsmith can be.

***

The reality that Ripley Under Ground does not reach its predecessor’s lofty heights is not really a criticism. The Talented Mr. Ripley, after all, is an acknowledged classic of the thriller genre. Even if Ripley Under Ground feels a bit repetitive, it is still the work of a master.

When I found out there were five books in the Ripley saga, I wondered where Highsmith would take the tale long term. Now I’m starting to see. In terms of storytelling, books one and two share the same beats. As a character study, however, Tom Ripley continues to evolve. Though I’m not sure I’ll ever plow to the very end (having heard that the final two titles feel like the cashing of a paycheck), I am intrigued to see Tom as he ages. I look at this series as the investigation into the heart of a very particular man, a nightmare of an American expatriate, just living the dream.