Somehow, this has been and probably always will be the most sacred book to me.

When you think about it a bit, the meaning of Calvin and Hobbes becomes quite a lot deeper than you would first expect. I’m always struck by how alone Calvin is. An only child and a six year old, he has no particular friends. His world is limited to his exasperated parents, occasional encounters with his neighbor Susie, a school-life that he constantly rejects, and his stuffed animal Hobbes. I don’t mean to garner sympathy for some poor lonely six year old, that’s completely against the point of quite a joyful comic series. Instead, I mean to call attention to how Calvin’s relative solitude highlights a pure engagement with the world that all humans fundamentally undertake on their own. The comic is a window into a young boy’s consciousness as he navigates the world around him and extends it over his surroundings. Hobbes, Calvin’s imaginary best friend and favorite interlocutor, is one such extension of Calvin’s consciousness that allows the reader to see the type of self-conversation at the heart of our condition. The pair have such a charismatic dynamic that you completely forget Hobbes is imaginary, this revealing the vibrant creativity and complexity in who we are, and our remarkable ability to derive companionship and comfort from ourselves. The over-the-top imaginary adventures Calvin and Hobbes proceed to go on serve to celebrate how ripe the world is for our mental shaping.

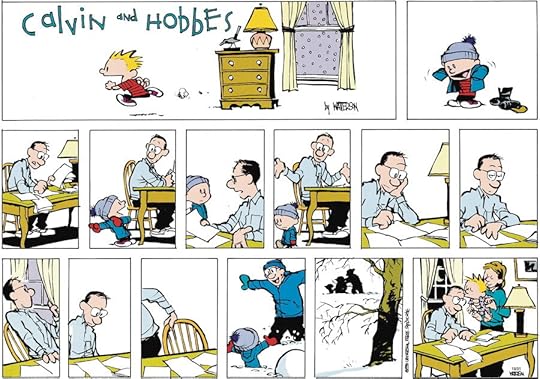

Ok, look, applying half-baked literary analysis to this is leaving a gross taste in my mouth. It’s such an uninspiring way to get such a profound point across. Calvin and Hobbes is a comic about a six year old navigating an expansive world by himself, who makes it his own. The comic is an ode to childhood, freedom, independence, creativity, joy, mischief, companionship, and more. It’s human and it’s life. As the pages turn and the motifs of the comics go from snowball fights and sledding to summer break and camping and then straight back to snowball fights and sledding again, each season feeling like a parody of the last and yet altogether new, I feel such a childlike wonder for the world that will never cease to remind me that even now, laden with conflated idealisms and stressful desires for the future, on some level I’ll always just be Spaceman Spiff running in circles around my backyard.

A final note: I don’t remember much of my childhood, but every-time I read Calvin and Hobbes I recall a certain other six year old only-child driving his parents crazy, talking to stuffed animals, and formulating wild adventures from the comforts (or confines) of his bathtub and backyard.

.

.