What do you think?

Rate this book

144 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2000

Rain, sun, two whole days of impenetrable fog, night winds whistling, winds far and near, nights of blue crystal, crystals of ozone. The graph of temperature against the hours of the day was sinuous, but not unpredictable. Nor, in fact, were their visions. The mountains filed so slowly past that the mind amused itself devising constructivist games to replace them.

His youth was almost over in any case, and still he was a stranger to love. He had ensconced himself in a world of fables and fairy tales, which had taught him nothing of practical use, but at least he had learnt that the story always goes on, presenting the hero with new and ever more unpredictable choices. Poverty and destitution would simply be another episode.

’And yet, at some point, the mediation had to give way, not so much by breaking down as by building up to the point where it became a world of its own, in whose signs it was possible to apprehend the world itself, in its primal nakedness.’To further embody this sentiment, Aira crafts his fictional account to resemble a biographic novel, writing as if citing letters that don’t actually exist and interspersing encyclopedic asides of biographical information. This seemingly factual information grows in the soil of fiction to become something far greater. ‘Reality was becoming immediate, like a novel.’

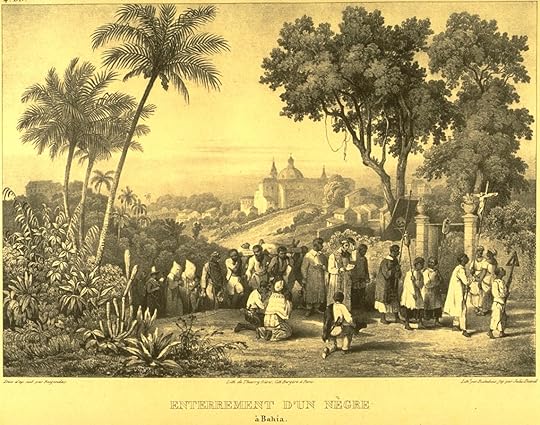

‘[Rugendas'] aim was to apprehend the world in its totality; and the way to do this, he believed, in conformity with a long tradition, was through vision…The artistic geographer had to capture the “physiognomy” of the landscape by picking out its characteristic “physiognomic” traits…The precise arrangement of physiognomic elements in the picture would speak volumes to the observer’s sensibility, conveying information not in the form of isolated features but features systematically interrelated so as to be intuitively grasped…The key to it all was “natural growth,” which is why the vegetable element occupied the foreground…’The artistic style has him reproduce exact, scientific elements in each painting to maintain an accurate image of reality, to highlight a specific moment in fluid history. As he reproduces small details of flowers to better capture the whole of a landscape, when drawing the Indian cattle raids, he comments that each toe, each tiny element of the Indians body is an expression on the whole of the man, which then must be reproduced, ‘seeing it as part of the multitudinous species, which would go on making nature. Continually reappearing from the wings, the Indians were, in their way, making history.’

‘The mules were driven by human intelligence and commercial interests, expertise in breeding and bloodlines. Everything was human; the farthest wilderness was steeped with sociability, and the sketches they had made, in so far as they had any value, stood as records of this permeation.’While storytelling is often the method for passing down history, Rugendas argues that ‘art was more useful that discourse.’ If all the storytellers fell silent, he argues that history could be better passed down by ‘a set of “tools,” which would enable mankind to reinvent what had happened in the past, with the innocent spontaneity of action.’ Rugendas argues for repetition, that all of humanity’s actions deserve to happen again to better learn from them. The repetitions of events lead to the telling of humanity, and each individual part speaks volumes to the whole. Like the reproduction of individual flora and fauna to create an accurate landscape, each scene, like the Indian raid, is an individual piece to the larger portrait of history. ‘The scenes would be part of the larger story of the raid, which in turn was a very minor episode in the ongoing clash of civilizations.’

’He was like a drunk at the bar of a squalid dive, fixing his gaze on a peeling wall, an empty bottle, the edge of a window frame, and seeing each object or detail emerge from the nothingness into which it had been plunged by his inner calm. Who cares what they are? asks the aesthete in a flight of paradox. What matters is that they are.’His new facial strangeness and ugliness opens up the beauty of strangeness in the world. Rugendas companion, Krauss, spends much time pondering the balance of the world, and with Rugendas, we see Rilke’s balance of artistry and solitude come to life in mortifying glory. The man leaves humanity all but behind to fully embody painting.

“Changing the subject is one of the most difficult arts to master, the key to almost all the others.”

"It was as if he had taken another step into the world of his paintings."

Both of them [Rugendas and his companion Krause, another painter] had been making these discrete sketches with the sole aim of composing stories, or scenes from stories. The scenes would be part of the larger story of the raid, which in turn was a very minor episode in the ongoing clash of civilizations.And then he illustrates it with a commonplace analogy as he occasionally also does elsewhere in the book:

There is an analogy that, although far from perfect, may shed some light on this process of reconstruction. Imagine a brilliant police detective summarizing his investigations for the husband of the victim, the widower. Thanks to his subtle deductions he has been able to “reconstruct” how the murder was committed; he does not know the identity of the murderer, but he has managed to work out everything else with an almost magical precision, as if he had seen it happen. And his interlocutor, the widower, who is, in fact, the murderer, has to admit that the detective is a genius, because it really did happen exactly as he says; yet at the same time, although of course he actually saw it happen and is the only living eyewitness as well as the culprit, he cannot match what happened with what the policeman is telling him, not because there are errors, large or small, in the account, or details out of place, but because the match is inconceivable, there is such an abyss between one story and the other, or between a story and the lack of a story, between the lived experience and the reconstruction (even when the reconstruction has been executed to perfection) that widower simply cannot see a relation between them; which leads him to conclude that he is innocent, that he did not kill his wife.I only wish there was more of his humorous side in the book as in the quoted last witty twist, something we find in abundance in his Artforum, another gem from this genius of his own experimental "procedure" of writing (not incidentally, it's the key term he uses for the act of imagining and painting in this novel).

Tuščiame danguje sprūstelėjo paukštis. Toli horizonte, tartum vidudienio žvaigždė, stovėjo vežimas. Kaip atkartoti tokias lygumas? Tačiau kelionė juk tikrai anksčiau ar vėliau bus atkartota. Dėl to jie turėjo būti atsargūs, nors kartu ir ryžtingi; atsarga reikalinga, kad kur nors nesuklystum taip, jog atkartoti taptų nebeįmanoma, o ryžtas - kad šis nuotykis būtų vertas dėmesio. (p. 34)

Tačiau šiuo slogiu laiku pastebėjo, kad išsipasakodamas Luizei nesugeba visko įamžinti dokumentiškai tiksliai. Arba, kitaip tariant, net ir užfiksavus viską (nes jai galėjo pasakoti bet ką), vis tiek lieka neišsakytų dalykų. Tai buvo vienas tų atvejų, kai visumos nepakanka. Galbūt dėl to, kad esama kitų "visumų", nors gal labiau todėl, kad didelis pasaulis, kuris sukasi lyg dangaus kūnai, susilieja su kosminiu judėjimu, ir taip kai kurios pusės lieka paslėptos amžiams. Norėdami tą įvardyti šiuolaikišku terminu, kurio laiškuose nėra, sakytume, kad tai - "retorinės elokucijos" problema. (p. 54-55)

Rašydamas stengėsi būti visiškai atviras. Tą grindė tokia mintimi: jei iš esmės tiek pat pastangų reikia sakant tiesą ir meluojant, kodėl tad nepasakius tiesos, nieko nenutylint, be dviprasmybių? Net jei tai tik eksperimentas. Tačiau lengviau pasakyti, nei padaryti, ypač dėl to, kad šiuo atveju daryti ir reiškia sakyti. (p. 58)

O juk iš tiesų juos supo gamta, kuri įkvepia, nes viskas joje nauja - Rugendas net prašydavo draugo patvirtinti, jog tai objektyvi tikrovė, o ne jo sąmonės trikdžių sukelta haliucinacija. Painios augmenijos apsuptyje paukščiai šaižiai ir padrikai giedojo nežinomas giesmes, nuo jų žingsnių išsilakstydavo patarškos ir gauruotos žiurkės, ant uolų atbrailų tykojo stotingos auksakailės pumos. Virš bedugnių sklandė susimąstęs kondoras. Bedugnių gelmėje buvo dar kitos bedugnės, o iš gilaus podirvio lyg bokštai stiebėsi medžiai. Jie matė, kaip sprogsta klykiantys gėlių žiedai, dideli ir mažulyčiai, kai kurios tų gėlių atrodė lyg su letenomis, kai kurios - lyg su apvaliais inkstais iš obuolio minkštimo. (p. 62)