What do you think?

Rate this book

263 pages, Pocket Book

First published January 1, 1991

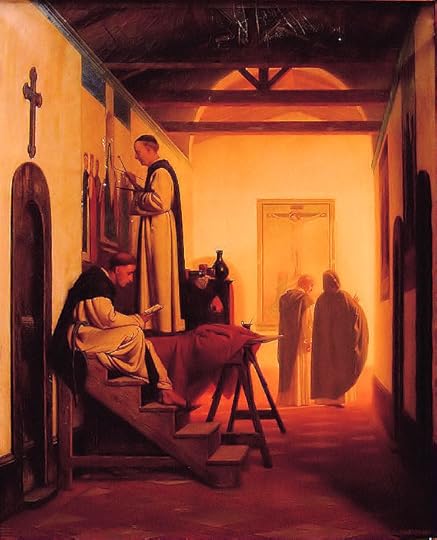

...the depiction of the marble is splattered with paint, applied by the artist after the surface of the fresco had dried. Didi-Huberman argues that Fra Angelico knew how to paint marble in a highly precise manner, suggesting that this portrayal is intended to be representative of more than just marble. Thus, the marble is not intended to be mimetic but figurative, representing the mystery of the incarnation of the word of God as described by Saint Bernardino as “the unfigurable in the figure."The blotches can carry other meanings. Here, in a detail from the San Marco fresco showing Christ at the Tomb, red splashes and crosses dot the grass. Are these simply impressionistic flowers? Didi-Huberman thinks not and interprets them as symbols of the stigmata.

Aquinas, the supposed champion of theological reason, will merely ask reason to bow down before this particular real, which he terms a mystery. If we admit that the real possesses the structure of a mystery, in the most radical sense of the word, then we have to admit that reality has lost its consistency; it is crumbling, exists only as an effect, as an illusion perhaps….Exegetical thinking does not save the “unity of the story”; on the contrary, it strips it bare and scatters the parts to the four winds of sense.Having spent the last month exploring the world of Byzantium and admiring all the magnificent mosaics in which millions of tesserae refract a transcendent world in shimmering glory, all this seemed very familiar to me. So was Fra Angelico part of the “Renaissance” as it flowered in Italy in his day? Or had he turned away from the assumed “humanistic” values to return to an earlier spiritual aesthetic? As Didi-Huberman writes:

“It is…pointless to try to ascertain whether Fra Angelico was “of his time” or not. Painting disturbs chronological history because it is always a complex and sly play of anachronisms. Fra Angelico was “modern” in many ways, but he was constantly displacing his own stylistic innovations….The eminently “medieval” character of [Fra Angelico’s] painting should not be envisioned as a delay, a defect, a negativity, but rather as an index of those long Middle Ages that Florence in the fifteenth century was far from repudiating.”Didi-Huberman's treatise was mostly over my head but the illustrations were magnificent. I found myself skimming the denser philosophical sections, but with the help of Bill Kerwin's excellent Goodreads review and some web resources, I did discover a whole new dimension to the works of a favorite artist.