What do you think?

Rate this book

296 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1980

Gury – that’s what he was called, as long as we’re on it. Among the amusements of that particular Gury I’d reference the followin: He was the one that adored scrapin and rollin over the slick on his sharps, which additionally resulted in us losin a client, and the undertakers, in contrast, findin one. I’ll provide evidence right away. In the days of the Archer, to make it more dangerous, but more excitin, the loners of both Shallow Reach shores arrange races on the weakenin ice. It happens in the outer darkness, intentionally without heavenly lights, and the folks cut figures as well as they can and hurry-scurry playin catch and chasin each other, without seein the holes and cracks. And that’s fraughtful.

It is wonderful outside – our native land. Kinda mother, but strikingly sly, deceitful. In the beginnin, overall, it appears to be – land like land, only poor, with nothin in it. But after you’ve made yourself at home, looked more carefully – there’s everythin in it…

And does not every Homo sapiens that is hurrying somewhere resemble Achilles? Nobody is able to catch up with one’s tortoise, reach something close by, whatever it could be. A survey of the late fall. Occupation – a passerby. Place of work – the street. The length of employment in the given field – eternity. The situation is not better with the other moving objects – they are not moving, making everything questionable. The migration of flocks lasts unacceptably long. They soar above the ribbed, dark maroon roofs, barely waving their wings.

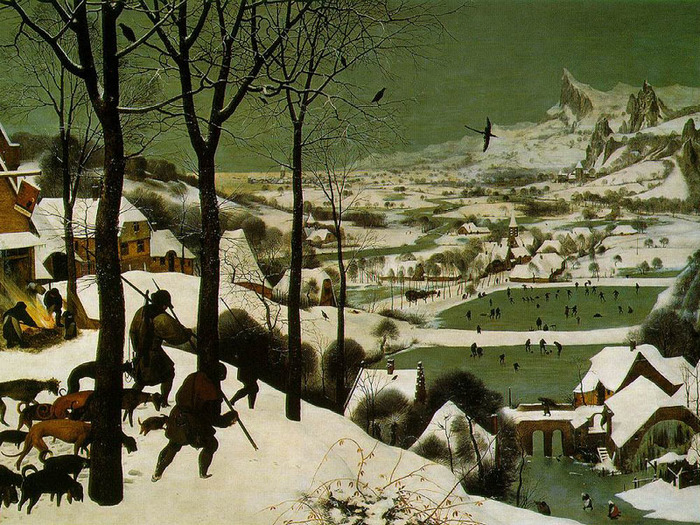

Take a good look at the cover of this book.Entre chien et loup is a French phrase which translates into English as 'between dog and wolf'. In French, the phrase is used for the hour of evening when the fading light makes it difficult to distinguish things clearly. Alexander Pushkin used the phrase in his verse novel, Eugene Onegin, and Sasha Sokolov quotes Pushkin's lines in one of the two epigraphs to this book:

Are there two crutches or just one?

Are there two animals or just one?

Is it a dog or a wolf?

Difficult to be certain, isn't it?

"I'm fond of friendly conversationWithout translation, I wouldn't have been able to savour this story of one-legged (and therefore one-shoed) Ilya Petrikeich Zynzyrela (sounds like Cinderella) who is also fond of friendly conversation and a glass or two. In a very enigmatical style, Ilya philosophises about his life as a 'grinder' of ice-skate blades (a Sharpenhauer!) in a village on the banks of the Volga—or the Itil, as he likes to call it, the Wolf river.

And of a glass or two

At dusk or entre chien et loup

As people say without translation."

So what have I read?Because, you see, the second epigraph Sasha Sokolov uses is from Boris Pasternak's Doctor Zhivago, and may or may not refer to the second main character, Yakov, who may or may not have been one-legged too, but who definitely owns a gun: The young man was a hunter.

Were there two one-legged men or just one?

How many dogs were mistaken for wolves at dusk?

How many crutches were used to kill the dogs?

Or were they killed with guns?

Does Ilya have a son.Enough, you say. Don't confuse us with further confusions.

Does Yakov have a father?

What does Orina have to do with both of them?

And what about Marina and Maria?

And the Lonesome Babes?

Confusion—it’s an inevitable faultSo ok, I will finish by mentioning a Russian classic that the translator feels is the most cited in Sokolov's text but which I didn't pick up on at all: A Hero of Our Time by Mikhail Lermontov.

Of clueless philosophers, passions, ages…

What kind of luck made me such a dolt

That I could not make sense of them all

Or rather could, but less and less, in stages?