What do you think?

Rate this book

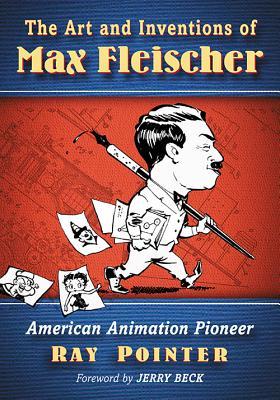

320 pages, Paperback

Published January 24, 2017

Animation should be an art. That is how I conceived it. But as I see what you fellows have done with it, is making it into a trade. Not an art, but a trade.

This is obviously a labor of love for Mr. Pointer. Many of the illustrations, copies of documents and more are from his person collection. And yet he still maintained objectivity in his analysis of some of the may problems with different animations, including the full length features. A good view of the studio, the Fleischers, and their work (there is a great comprehensive list of everything produced at the end of the book.)

Disney may have the accolades, and he deserved them. Pointer recounts a story:For Max, the concern was strictly fluid action for its own sake. Walt Disney was more focused on the context of the action, and the stories of his Sweat Box Pencil Test sessions have become legendary. Fleischer Animator Berny Wolf told of the famous 13 corrections he made for a scene of the Jimmy Durante pelican characters in Elmer the Elephant (1936):There is something to admire in the ability to notice a small detail that throws everything off.

Walt looked at it and said, “Who did that?” I slumped down in the chair and said in a little voice, “I did.” Walt looked back with one eyebrow up, he said, “You know better than that!” So I took my stuff out of the reel and went back to my desk with it. And for the next week I handed in my corrections. And I didn’t know what the Hell was wrong with them. I made 13 corrections on the one scene. I had it back in Sweat Box at least six times. The bulk of the time Walt wouldn’t even pay any attention to it. Jackson directed it. So I said what’s wrong with it? And he said (whispering), “Berny, I don’t know what’s wrong with it.” He’d say “Why don’t you ask ‘so-and-so’”? I asked “so-and-so” and he wouldn’t know. I’m going crazy. The next time in the Sweat Box, Walt says, “When are you going to correct that?” I get back to my desk and take the whole reel out down to my room to see if I can figure what the Hell it was. And I looked at everybody else’s as well as mine, and I finally caught it. It was ever so subtle. The action flow went (left to right). My Durante went (left to right). So I flopped my drawings, re-shot it (with) bottom lights. (Now) he went (right to left). I get it in the reel and Walt says, “Finally! Finally!”