Reading books about Zen can be a very frustrating experience. Expressions like “everything is nothing” and “the river no longer yearns to return to the ocean, the river is ocean” or “time and being are identical - exactly the same.” You have to just pass over it, nod, and move on.

It makes sense to me, however, when the author writes, “We practice this by simply investigating what is behind everything…as you continue this investigation, you will find that there is nothing behind ‘behind.” “This is the “nothing” that can recognize things as it is.”

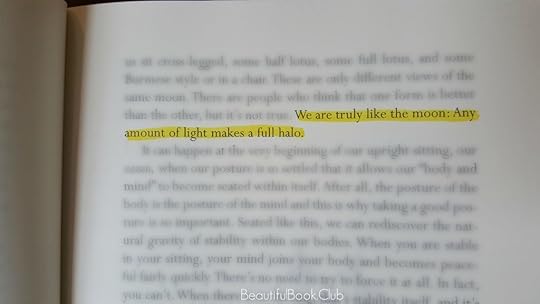

The goal of Zen, if there is one, is to see the world as it is. The practice is to give the mind the opportunity, through Zazen, to directly perceive the errors that our minds project in front of and on to everything that we experience.

Jakusho Kwong had the unique opportunity to live and study with one of the founders of Zen in the United States, Shunryu Suzuki-roshi, author of “Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind” and many lectures and other books. The stories of the great master are personal and revealing, and worth the price to read this book.

In the end, of course, it is about Zen, and writing about Zen can only take the reader just so far. The practice of Zen, sitting in the zazen posture contemplating and investigating what is “behind” the world we perceive is necessary to really understand what it is all about.

This book is beautifully illustrated with the author’s own calligraphy. In both his teaching and drawing, Kwong has a unique style which lends itself to an enriched understanding of Zen.