Letters from Switzerland. More of a geographic discourse, very hill and dale he saw, to the tune of several hundred pages. Still well written, just rather dull.

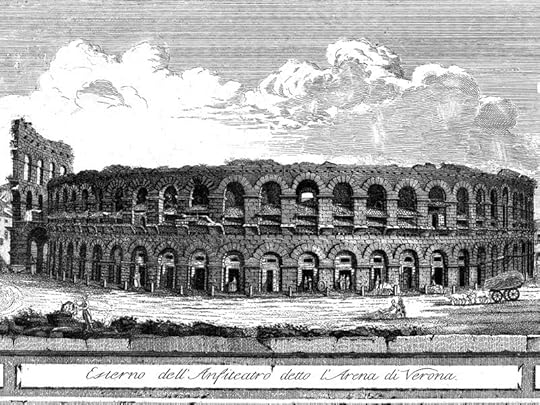

Letters from Italy. No this on the other hand, approaches the same candid nature as his Autobiography. Some of it is hysterically funny, some sad (when he realized that a very famous artist's pictures were complete fabrications, indicating that the artist had never even been to the location, making his art a lie). His comments on the Roman Chuch, as observed while in Rome, are funny - and sad, although accurate, from the Christian perspective. His observations about people from the different regions in Italy are very apt - and still pretty accurate, today. Really, a great read. I'd give Lettters from Italy a 5+.