What do you think?

Rate this book

256 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2016

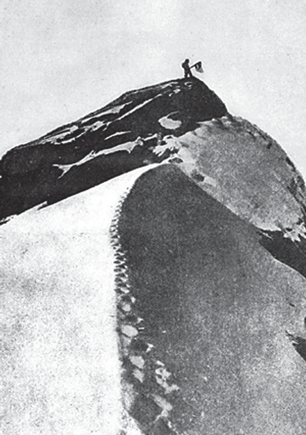

I write in Catalan and translate myself into Spanish. Sometimes I even write in both languages at the same time. After I finish, I translate the bilingual book into a one-language book. The process of translating the text gives you new perspectives on it and makes you look carefully through each sentence. For me, doing a translation is the best way to proof a text. In the case of the English translation, I worked closely with Mara Faye Lethem. English is an appropriate language for this kind of work, because it is a book about something very sharp, which is ice. It is transparent, sharp and creates constellations in the form of snowflakes. For me, the language has sharp words and it is easy to create new concepts with it. I was glad that Brother in Ice was translated by her.Brother in Ice is a "hybrid novel", as the publisher describes it, "part research notes, part fictionalised diary, and part travelogue", with pictures and Kopf's own artwork, centering around the theme of polar exploration.

The writing process comes from both journaling and rewriting to shape a literary artifact where everything is connected through a metaphor. In Brother in Ice the metaphor was polar exploring. This metaphor is something I research quite deeply as it gives a structure to the whole book; it’s the lens through I will look at reality during a long period of time. In real life there is not a general concept, things are often meaningless and disperse, so I reshape my experience into something that makes some sense, that illuminates some kind of aspect of life beyond the real people and facts that inspired it.The clearest example is the moving portrayal of her relationship with her autistic brother, whose sobriquet gives the novel it's title (or perhaps more accurately the novel gives him the sobriquet):

I love everything I've read ABOUT this book, including in the book itself.In a way my own review is intended as a contribution to that - I enjoyed talking here about the book at times more than I did reading it. And I will end by directing the reader to some interviews about the book, which include the sources for the quotes above:

BUT.

I don't think BROTHER IN ICE quite delivers on its promises.

Because I’m not interested in the polar explorers in and of themselves, but rather in the idea of investigation, of seeking out something in an unstable space. I’d like to talk about all that as a metaphor, because what interests me is the possibility of an epic, a new epic, without foes or enemies; an epic involving oneself and an idea. Like the epic that artists and writers undertake.I struggled with the novelistic segments. The degree to which autofiction mirrors a writer’s actual life matters more to some readers than others. And perhaps the amount it matters is also dependent on how much a reader is interested in those actual life events, be they lightly or heavily fictionalized. The question nagged at me of whether the protagonist’s personal life history was carefully orchestrated by the author to appear haphazardly exploratory in its telling, or whether it was actually drafted with little artifice in this somewhat random, journal-like manner. I don’t know why this bothers me but I found it distracting, especially when at times the autofiction sections read so much like what could easily be a laundry list of thinly veiled events in the author’s life. It screamed memoir, yet it is not. Why? Why should I care? I don’t know. This is why I can’t read Knausgård. That said, I enjoyed this more than Book One of My Struggle, which is where I stopped with him. I did find some of Kopf’s observations on writing to be quite perceptive:

Narration as a place to fictionalize memory, which is constructed, partial, voluble, and will be reinvented in the text and therefore always destroyed again in the text.Which might succinctly describe what is happening in the book itself. In the end Kopf's work succeeded most for me in generating reflection on the creative process and how integrated it is (or has the potential to be) with our everyday lives. Though I was initially intrigued by the polar exploration theme, its integration into the text was erratic, making for an uneven reading experience.

“The laws of each family are created within it, and are practically devoid of external judgements-- except for serious cases such as homicide, violence, and sexual abuse. This “law,” which generates a certain lack of protection against injustice, is usually written off as family patterns. Therefore, the unequal distribution of emotional and economic resources (which are often impossible to “carve up” equally) of expectations and demands, and also of the enforcement or not of norms (linked to random circumstances such as the gender of the infant or birth order) usually go unpunished, and in the best case scenario, are left to be resolved among siblings.”