Ah, Bilitis. I feel a great loss to learn in the notes that you are a fiction created by a French fool fond of Greek and the erotic. A friend of Wilde was Pierre Louÿs, did you know? And Claude Debussy wrote tunes for some of the songs Louÿs wrote as Bilitis? ... I really was genuinely moved to think that maybe this work was touching and eternal, but instead some limp-wristed dandy did the writing--

Whatever. What I found moving was the thought of Bilitis. Let's skip the bit where I bought it like a fool.

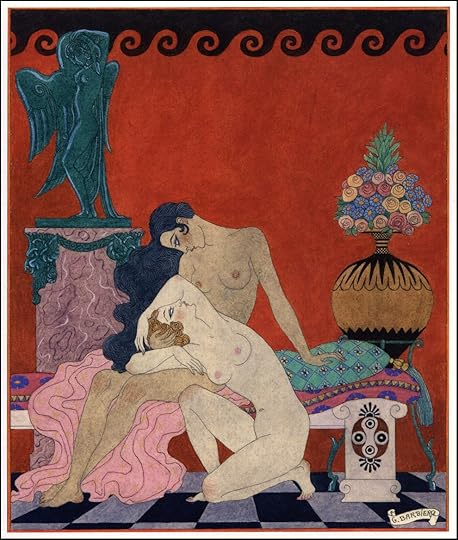

This is worth the read. If you take the tale sincerely, it's the collected poems of a young girl who leaves her home of Pamphylia at 16 for the Isle of Lesbos, not aware of what she steps into for here Sappho still reigns; and then, after the end of a 10 year relationship with a woman she had married, Bilitis briefly goes through a villain era before leaving for Cyprus, where she will eventually die before the age of 40--but not before she attempts an artistic, literary stint, becomes a popular courtesan, then a pimp, suffers more sexual assault and rape (ah yes, this was an issue for her also, briefly, while at home in Pamphylia), then declines in fame and usefulness as a courtesan as her body ages, and finally, she is wasted away by some disease. At the height of her grief following her break-up with her wife, Mnasidika, Bilitis writes a funeral chant for herself, wishing to die. Before the book's end, she writes three epitaphs for her grave. She got her wish.

Ignoring how I just realized I was swindled here 20 minutes ago ... I was moved by the ... slow progression of Bilitis as a person. I will give this to Louÿs, he does character work *very* well, and his initial set-up where he vouches himself as a translator effectively serves his narrative: there's not many segments where Louÿs goes silent in writing Bilitis' tale, but in the gaps he does leave, the way he works up to threads of plot or feeling, then drops it and picks it up later after some change has occurred and now Bilitis is nursing *that* variation on this wound instead ... very clever. Felt real and human.

The care and attention paid to the erotic interest of these fictional lesbians involved felt very natural to me, a real lesbian. I was wooed by the intensity of Bilitis' feeling and need. I was stressed when I watched Bilitis shift from someone carefree and freely loving to a person more jealous and paranoid about her relationship with her wife. The implication is that her wife cheated on her, and that's what brought this relationship down, and the tension in the poems that precede the final break-up had me balanced on a knife's edge. Bilitis' poems where she details how she'd do anything to keep her lover (before they break up), and her desperation for her lover to see her just one more time (after the break up), to the tune of, "I ask it of you, beg it of you, and think that the remainder of my life hangs on your answer." ... Alright queen, go off, hard same. And then she hooks up and toys with this girl that Bilitis knew had a crush on her and her wife while trying to cope? My god the writing for those poems that detail it ... now THAT is fire and emotion.

The thing that really got me about the writing of Bilitis is the complete sincerity, I think. There's the things you say, the things you can only reference in passing, and the things you mean to say--WOULD say--if only you were braver. Louÿs takes that last one and declares, "Fuck it! Bilitis is capable of 200% emotion now." And I appreciate that he writes Bilitis as a needy, desperate lover--unlike the rest of us, who presumably pretend we are not so while displaying all the symptoms privately. Bilitis by nature of being a supposed songwriter and poet is *not* private, which I suppose just adds another layer of intent and meaning to every poem put on paper and attributed to her pen and narrative. There is something painfully sad about watching her life go downhill as soon as she leaves Lesbos. The spit and fire is leeched out of her, and when it returns, it's with the grieving of a woman used, objectified, and reduced. Her grief then becomes some of the most potent parts about her character, as is her attempts to console herself about the aging of her body, the uses of her wisdom and cleverness in a sea of fellow courtesans where she becomes replaced by youth. There is also, of course, Bilitis' never-ending disgust and hatred leveled at perverts, pedophiles, and rapists, and her despair at witnessing or experiencing any of these things is likewise remarkably well-put coming from a male French writer who may or may not have been gay himself? Who knows. Bilitis seems to be trying to work out what confidence she can still find in her life in this last segment, despite clearly having said goodbye to her happiest days in Lesbos, and her swan dive into misery *after* she left Lesbos ... watching it left me quite troubled.

I may be giving Louÿs more credit than he deserves overall. I don't know the context with which his work was received or read. (Initially. Obviously American lesbians in the 1950s will pounce on it and name an organization after this text--the Daughters of Bilitis.) More likely than not he wrote all this woman-on-woman loving in The Songs of Bilitis and in his other works hoping to titillate his male peers. It is ironic that one of the most historically iconic lesbian writers is in fact a man, who as far as I know may not even have joined the lesbian crew by being trans. There is, however, the power of dead authors, which is to say fuck Louÿs, he's dead, I'm alive, and I will do as I please. Also, Louÿs DID write some banging lines, and he did it quite a lot, and I would be remiss to ignore all that.

When Bilitis said, "If one has suffered, I can scarcely feel it. If one has loved, I have loved more than she." When Bilitis said, "If life is a long dream, what use is there in resisting it?"

When Bilitis said, "The night is fading. The stars are far away. Now the very latest courtesans have all gone homewards with their paramours. And I, in the morning rain, write these verses in the sand. ... Those who will love when I am gone, will sing my songs together, in the dark."

When Bilitis said, "In gratitude to you who have paused here, I wish you this fate: May you be loved, but not love," and said, "I have sung of how I have loved. If I have lived well, Passer-by, tell your daughter."