What do you think?

Rate this book

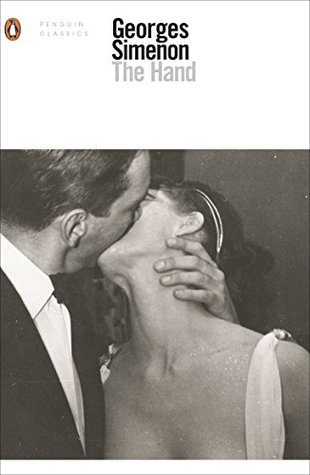

162 pages, Kindle Edition

First published January 1, 1968

‘Saturday morning, or Friday evening, Isabel or I, or both of us, would go and pick up the girls in Litchfield. We would present, in the car, the image of a united family.

Except that I no longer believed in the family. I no longer believed in anything. Not in myself, not in other people. Basically, I no longer believed in mankind and I was beginning to understand why Ray’s father had shot himself in the head.’

‘Modest, self-effacing, she is actually the most arrogant woman I have ever met. She never allows the slightest fault to show, none of our little human weaknesses.’

‘I don’t know any more. I lean now towards one hypothesis, now towards another. I live under her gaze, like a microbe under the microscope, and sometimes I hate her.’

‘If they could have known, every last one of them, how I hated her! But she was the only one who knew. For I had understood. I had sought the meaning of her look for a long time. I had made various suppositions without thinking of the quite simple truth.’

‘Strangers who live together, eat at the same table, undress in front of each other and sleep in the same room. Strangers who talk together as husband and wife.’

‘She watches me live, knows my slightest reactions and doubtless my least little thought . . . She never says a word that might suggest that. She remains quiet and serene.’

‘Ray had to remain the man I had imagined, hard on himself and on others, cold and ambitious, the strong man on whom I had taken revenge against all the strong men on this earth. I did not want a Ray disgusted with money and success.’

‘That night, I had discovered that for the entire time I had known him I had never stopped envying and hating him.

I was not the friend and neither was I the husband, the father, the citizen whose roles I had played. It was just a façade. The whited sepulchre of the scriptures.’

‘The children must have noticed that tension. I sensed a certain wariness, a certain disapproval in my daughters, especially when I pour myself a drink.’

‘As for Cecilia, I don’t know. She remains an enigma, and I would not be surprised if she possesses quite a strong personality. She watches us live, and I’m almost convinced that she does not approve of us, that the only thing she feels for us is a certain disdain.’

A Donald è bastata una serata sconsiderata, una sbronza gigantesca, un gesto codardo nei confronti di un amico e si spezza un equilibrio costruito in anni di vita irreprensibile e ipocrita. Si volta indietro e analizza tutta la sua vita passata, rimugina, si arrovella, si rode e pian piano scivola dall'ansia e dall'angoscia alla paranoia e alla psicosi. E ovviamente la storia finisce malissimo.

Simenon è un grande rimuginatore: prende una persona normale, la inserisce in un ambiente convenzionale, la lascia vivere tranquilla fin a quando arriva l'epifania: una cuginetta in visita, una gravidanza inattesa, la visita di un fratello scappato dal carcere, e di colpo al protagonista si ribalta il mondo. E inizia a precipitare nel baratro dell'ossessione fino alla prevedibile drammatica conclusione.

E' uno schema visto e rivisto nei "romans durs" di Simenon, ma funziona sempre. Ha funzionato anche questa volta, nonostante qualche incongruenza, cosa strana per il maestro.

Per esempio, poche pagine dopo aver lavato i piatti insieme all'amica, Isabel carica una lavastoviglie comparsa dal nulla.

Sono caduti quasi 2 metri di neve, e l'amico precipita nella scarpata e batte la testa e muore. Un po', di neve me ne intendo, e anche di scarpate coperte da 2 metri: la neve fresca così alta si comporta come un materasso. Si affonda un po' poi ci si ferma. Non si sbatte la testa da nessuna parte, a meno che non si venga travolti da una valanga, ma non è il caso: è una piccola scarpata vicino a casa. Io non c'ero, ma mi sembra un tantino improbabile.

Ci aggiungiamo che l'amante si chiama Mona. Ecco, ho faticato parecchissimo a prenderla sul serio.