As a writer of textbooks in his previous career, Steve Sheinkin (pronounced "Shen-kin") had the expertise to craft tight, informationally correct nonfiction, but Bomb: The Race to Build—and Steal—the World's Most Dangerous Weapon proves that his abilities range far beyond that. Bomb was inundated with major youth media awards and nominations (including a 2013 Newbery Honor as well as that year's Robert F. Sibert Medal) for good reason: it's one of the most complexly interwoven nonfiction accounts I've read, probably the most complicated I've seen attempted for young readers, yet Steve Sheinkin adroitly keeps the waters from getting muddied despite all the names, places, and international rivalries that vie for the reader's attention. Bomb is an ambitious book and Steve Sheinkin knew it from the start, masterfully plotting its course for maximum clarity and impact, a monumental task that reaped rich rewards. The practical and philosophical takeaways from this book are virtually limitless, following a particularly volatile fault line of twentieth-century history and extracting the lessons to be learned while thrilling us with the buildup to the unveiling of the deadliest weapon to that point in human history. The climax is well worth the one-hundred-seventy-five-page wait.

Otto Hahn's accidental discovery of nuclear fission in 1938 opened the door for diverse applications of the atom-splitting process, and scientists quickly realized that the most ominous of these applications was the hypothetical atomic bomb, an explosive of much greater power than previously deemed possible. A detonation triggered by uranium fission could wipe out any city on the planet, the largest metropolises not excluded. When Albert Einstein, who fled Germany as Adolf Hitler rose to power, wrote to United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt to express concern over this advanced weaponry falling into the wrong hands, Roosevelt heeded the message and compiled an elite team of American scientists to explore the possibility of creating an atom bomb. Because Otto Hahn, a German physicist, had discovered fission, America had to assume Hitler was closer to obtaining a uranium bomb than any other world leader, and that meant the outcome of World War II would not be assured until Germany was completely neutralized. The war was trending in the Allies' favor, but a few atomic bombs could swing the balance in a matter of hours. It was imperative to prevent Hitler from getting his hands on weaponry of this magnitude.

"If the baby doesn't cry, the mother doesn't know what he needs...Ask for anything you need. There will be no refusals!"

—Joseph Stalin, Bomb, P. 202

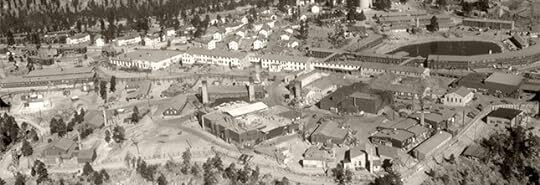

President Roosevelt assembled his team of super-scientists in the remote landscape of Los Alamos, New Mexico, headed by one of the brilliant minds of his day: skinny, physically unimposing J. Robert Oppenheimer, a science prodigy who was chomping at the bit to aid the American war effort. Oppenheimer's team included premier scientists from the U.S. and abroad, gathered on the Roosevelt administration's dime to solve the lingering problems of nuclear fission and beat Hitler to the punch in creating an atomic weapon. Not every member of the team was interested in helping the Allies defeat the Axis powers, however. The Soviet Union was as desperate as the U. S. to win the race to create an atomic bomb, but had fallen hopelessly behind the other Allies. While officially a friend of the U.S., Great Britain, and France in World War II, the Soviet Union—headed by Joseph Stalin, whose goal was the worldwide spread of communism—was opposed to the democracy of those countries. The only way to leapfrog to the vanguard of weapons technology would be for the Soviet Union to place spies in America who could gain security clearance to work on the teams at Los Alamos and elsewhere and relay what they learned back to their mother country. The U.S. government knew this was going on and kept close watch on suspected Soviet sympathizers nationwide, so their espionage had to be conducted near flawlessly, for anyone caught helping the enemy would likely be executed. As the race commenced between the U.S. and Germany to finish the world's first atomic weapon, the spy contest between the Soviet Union and United States also began.

Bomb takes us around the world to listen in on clandestine meetings between spies, dogged by special agents charged with apprehending them. Any slip-up by a spy could mean their own death, and failure by government agents to disrupt their operation could undo the intensive work performed by Oppenheimer and associates in the New Mexico desert. At the same time, another spy game was going on: convinced that Germany was way ahead in the bomb race, Norwegian agents were dispatched to thwart the Führer's quest for nuclear supremacy, targeting Germany's heavy-water processing plant in the snowy Norwegian wilderness for sabotage. This heavy-water facility was the only one of its kind worldwide, and destroying it would delay Hitler in his race to procure the atom bomb. Special-ops skiers zoomed over the snowy Norwegian landscape to mount a covert assault on the plant, but Germany was ready, and a chess match ensued between subversives bent on destroying Hitler's priceless resource and the German government, determined to protect what they had. The ski-clad Norwegians spent many tense nights sneaking through the darkness to put one over on their adversary, knowing they would be violently executed if caught. But if they could cease the flow of heavy water to German scientists who needed it for nuclear testing, the risk of their own lives was acceptable to them.

"A man who is a man goes on until he can go no further—and then goes twice as far."

—An old Norwegian saying, quoted on P. 57 of Bomb

As Oppenheimer and his fellow geniuses closed in on the formula for a uranium bomb, they had no idea their research was being funneled to the Soviet Union. Scientists Ted Hall and Klaus Fuchs were the eyes and ears of the Soviet Union in Los Alamos, so as America verged on the greatest discovery in military history, the Soviets weren't far behind, avoiding many dead-ends that Oppenheimer lost time on. But even as the Allies took down Germany, the need for an atomic bomb did not lessen: Japan would not concede defeat in the war, and the U.S. president also knew he had to make a show of strength to put Joseph Stalin on notice. What better way to accomplish both ends than dropping the world's first atomic bomb? Even Stalin would blanch at the prospect of a weapon that could burn a city like Moscow off the map. The technology finally in place—at least theoretically—after years of grueling intellectual labor by Oppenheimer and his support staff, a test was scheduled for the new bomb. Would the science work in real life?

The scenes leading up to what happened at the Trinity Test Site feel like a dramatic film climax, the clock ticking down to unimaginable destruction as Oppenheimer and the other scientists crouched behind protective layers six miles away. Would their hard work bear fruit, or was the bomb functional only in the abstract? And which outcome was preferable for the scientists as human beings who knew how many lives the bomb could be used to snuff out? The moment of detonation comes across as though we were hunkered right beside Oppenheimer, fearful of the monster that had been awakened and could never be slain, feeling the scorching heat from the blast on our face as we're surrounded by jubilant men of science who had devoted years of their lives to making this happen. The world could never be the same again.

Yet the emotion of that night dims next to the fear of the bomb being used for real as Japan continued to reject demands that they surrender. A mainland invasion of Japan could cost the U.S. hundreds of thousands of soldiers' lives, and newly inaugurated President Harry Truman refused to sign off on that if he had an alternative. Warning the Japanese government of mass destruction in the Land of the Rising Sun if they persisted in fighting, Truman gave the order to drop the new secret weapon by airplane on the city of Hiroshima. Details of the flight are relayed with breathless immediacy, putting us in the aircraft as it delivered its devastating payload to a metropolis full of unsuspecting civilians. The moment is haunting in its gravitas. Everything that comes before this in Bomb is but prelude to the Hiroshima strike, a tragedy of biblical proportions visited on a country that didn't know such an attack was possible. Even the Los Alamos scientists were distraught at the destruction they had helped engineer: hundreds of thousands of dead and mutilated Japanese, with more perishing daily from radiation poisoning. And the horror was not over. Still refusing to capitulate to the Allies' demand for unconditional surrender, Japan was hit by an atomic bomb in Nagasaki that killed hundreds of thousands more, and Emperor Hirohito had seen enough. Overriding his intransigent military advisers, the emperor decreed Japan's surrender. They would accept whatever consequences there were for their part in the war.

World War II was over, but Oppenheimer's role in weapons design was not. Unnerved by the effects of the atomic bomb, Oppenheimer argued for conciliatory talks with the Soviet Union, pointing out that they would be capable of creating uranium bombs sooner or later. In fact, the Soviets were closer to an atomic bomb than Oppenheimer imagined; their spies at Los Alamos had given them such an advantage that the Soviets were able to test their own atom bomb just four years after World War II ended. The U.S. government was dumbfounded; how were their estimates of Soviet nuclear advancement so far off the mark? Closer scrutiny gave indication of the spying at Los Alamos, and the FBI was brought in to ferret out the perpetrators. Klaus Fuchs, Ted Hall, and others found themselves stalked by agents years after they gave up espionage; the government would not be appeased by vague answers and denials of wrongdoing. Over the next several years many American and international spies who leaked classified data to the Soviets were brought up on charges and convicted, imprisoned for decades or executed in some cases. Even Oppenheimer, who'd shown interest in the Communist Party in the 1930s, was investigated, though there was no evidence he did anything wrong. Atomic technology grew more extreme, evolving into the hydrogen bomb, which worked by nuclear fusion rather than fission, much like stars. The first hydrogen bomb tested by the U.S. was equal to ten million tons of TNT explosives; in comparison, the uranium bomb tested at Trinity was equivalent to only twenty thousand tons of TNT. The arms race between the U.S. and Soviet Union escalated as both sides built bigger and bigger hydrogen bombs at faster and faster rates, enough to destroy the world many times over. Pandora's Box had been opened, and the planet would never be quite as safe again. What will the future of nuclear energy hold?

"The peoples of this world must unite or they will perish."

—J. Robert Oppenheimer, Bomb, P. 215

The strength of Bomb isn't just its compelling central storylines, but all the bits and pieces that merit contemplation. The engineering at Los Alamos of the first atomic weapon was a marvel of human intelligence and cooperation, but how was it achieved? Among serious thoughts about the global ramifications of atomic warfare, there are anecdotes that highlight the quirkiness of the scientists who worked on the project. These were brilliant men with eccentric minds—if they didn't think differently from others, how could they come up with innovative ideas?—and their behavior at Los Alamos showed it. To accomplish anything as momentous as what they were attempting, weird minds have to be in the mix: diverse, odd, original thinkers whose mental energy melds into something otherwise inconceivable. The default setting of average minds is to denounce those they consider strange: to marginalize, ostracize, and banish them to their own devices, but huge leaps in progress don't occur without extraordinary minds. Society needs offbeat thinkers who make us uncomfortable if we're to unlock our full potential; we hurt ourselves every time we succumb to the knee-jerk reaction to shoot down strange birds. They often fly to destinations uncharted and unconsidered, and we need them to challenge our assumptions.

Spy rings are intriguing, heart-pounding fun, which is why we love movies, television series, and books about them. The more daring and intricate the plot, the better. But there are heavy consequences for spying, and Bomb recounts some of them for our edification. People are jailed, murdered, their personal lives torn apart by their forays into espionage. It's a dark thrill when you're getting away with it, but you have to live with your actions for the remainder of your life, dreading reprisal if you're found out by authorities who have a bone to pick with you. Harry Gold, a spy we meet in the prologue to Bomb, learned this lesson the rough way: his relationship with the love of his life was wrecked by anxiety that his past indiscretions on behalf of the Soviets could be uncovered at any time. He wanted to marry his beloved, but what kind of future could he offer? The spy game isn't just unflappable operatives outsmarting the best counteragents of powerful countries; mostly it's real people facing the music for acts considered treasonous by sovereign entities, and treason typically spells death for those involved. Bomb illuminates not only the excitement of spying, but the inglorious consequences.

Steve Sheinkin doesn't take a political position on the arms race issue, but he makes clear that it's a problem when any nation has the capability to make war on a scale that could render the planet unlivable for people. That troubling scenario is the descendent of Oppenheimer's experiments at Los Alamos, pacifist though he was at his core. Sanguinary as the American Civil War and World War I were, they were still just humans killing each other with guns, but atomic warfare changed that. Mankind as a species now had the power to commit suicide, and as nuclear arms proliferated globally, they came into the hands of unstable leaders whose next actions were anyone's guess. In the words of Paul Tibbets, who piloted the Enola Gay on its mission to take out Hiroshima, "We were sobered by the knowledge that the world would never be the same...War, the scourge of the human race since time began, now held terrors beyond belief." Can we survive our own worst impulses? It's an open-ended question, as are so many raised by Bomb. We reveal the answer day by day, year by year, century by century, and hope the answer will still be to our liking tomorrow.

"In the end, this is a difficult story to sum up. The making of the atomic bomb is one of history's most amazing examples of teamwork and genius and poise under pressure. But it's also the story of how humans created a weapon capable of wiping our species off the planet. It's a story with no end in sight.

And, like it or not, you're in it."

—Bomb, P. 236

Newbery Honor citations are rare for nonfiction, but was Bomb deserving? The book is definitely Newbery quality, in my opinion—I would rank it ahead of Katherine Applegate's The One and Only Ivan, which won the 2013 Newbery Medal— but there are a number of books I'd put ahead of Bomb for the 2013 Newberys. I can't even say it's the year's best junior nonfiction offering; that would probably be Abraham Lincoln & Frederick Douglass: The Story Behind an American Friendship by Russell Freedman, who was the king of juvenile nonfiction for more than four decades. But Bomb is topnotch literature, and we're lucky to have it. Steve Sheinkin's approach is that of a sensitive storyteller, not just a provider of information, and we benefit from his insight into the race among the world's powers for the first atomic arsenal. For readers interested in dramatic history characterized by subplots and high stakes, Bomb is the book for you.

Testing the first atomic bomb

Testing the first atomic bomb