What do you think?

Rate this book

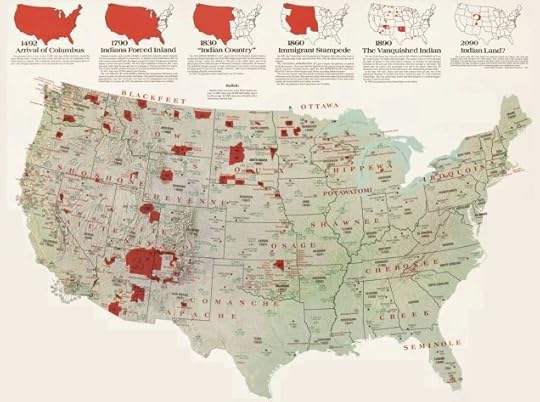

In a sweeping narrative, Peter Cozzens tells the story of the wars and negotiations that destroyed native ways of life as the American nation continued its expansion onto traditional tribal lands after the civil war.

Cozzens illuminates the encroachment experienced by the tribes and the tribal conflicts over whether to fight or make peace, and explores the squalid lives of soldiers posted to the frontier and the ethical quandaries faced by generals who often sympathized with their native enemies.

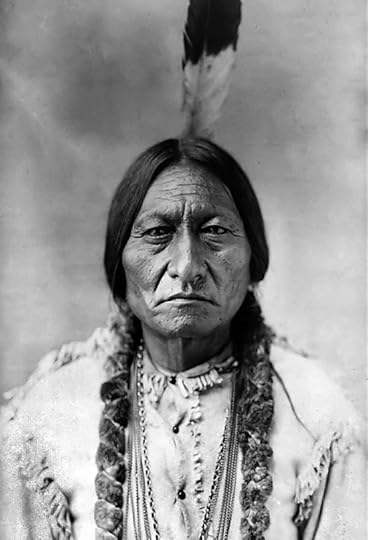

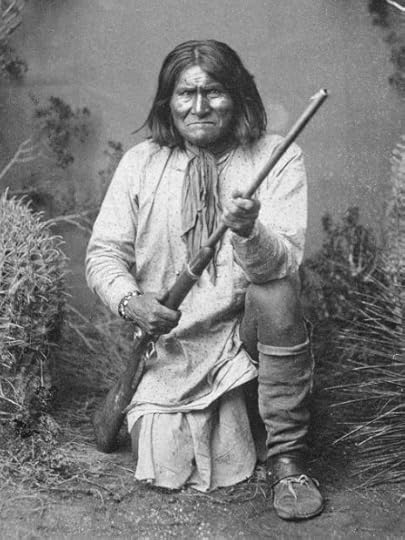

As the action moves from Kansas and Nebraska to the Southwestern desert to the Dakotas and the Pacific Northwest, we encounter a cast of fascinating characters, including Custer, Sherman, Grant, and a host of other military and political figures, as well as great native leaders such as Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, Geronimo and Red Cloud. For the first time The Earth Is Weeping brings them all together in the fullest account to date of how the West was won - and lost.

791 pages, Kindle Edition

First published October 25, 2016

Resistance from the infantry might have been minimal; the young Oglala chief American Horse said that many soldiers appeared to be paralyzed with fear. It soon turned into the sort of close-order combat the Lakotas called “stirring gravy.” As infantrymen fell with arrow wounds, dismounted warriors descended upon them, first counting coup and then smashing their skulls with war clubs. American Horse landed [Captain William Judd] Fetterman a disabling blow and then cut his throat, while the officer who had bragged about taking Red Cloud’s scalp shot himself in the temple. The infantry and the cavalry fought and died apart. [Lieutenant George Washington] Grummond fell early, decapitating a warrior with his sword before a blow from a war club dropped [him]…

Captain Jack snapped his revolver in Canby’s face, but the cap popped harmlessly. As Canby stood frozen, Captain Jack cocked the hammer again and shot him through his left eye. To everyone’s amazement, the mortally wounded general rose to his feet and ran forty or fifty yards until Captain Jack and the warrior Ellen’s Man caught up with him. Ellen’s Man shoved his rifle against Canby’s head and fired, and Captain Jack stabbed Canby in the throat for good measure.

Put yourself in his place and let the white man ask himself the question, What would I do if treated as the Indian has been and is? Suppose a race superior to mine were to land upon the shores of this great continent, trade or cheat us out of our land foot by foot, gradually encroach upon our domain until we were finally driven, a degraded demoralized band, into a small corner of the continent, where to live at all it was necessary to steal, perhaps to do worse? Suppose that in a spirit of justice, this superior race should recognize the fact that it was in duty bound to place food in our mouths and blankets on our backs, what would we do in the premises? I have seen one who hates an Indian as he does a snake, and thinks there is no good Indian but a dead one, on having the proposition put to him in this way, grind his teeth in rage and exclaim,” I would cut the heart out of every one I could lay my hands on,” and so he would; and so we all would.

First, Sitting Bull set his people straight on the Great Father. The agents had lied: white men did not hold the Great Father sacred. On the contrary, Sitting Bull told them, “half the people in the hotels were always making fun of him and trying to get him out of his place and some other man into his place.” As for members of Congress, “they loved their whores more than their wives.” And like most white men, they drank too much. (p. 436)