What do you think?

Rate this book

428 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1968

It may be the commencement of spring or perhaps the end of summer; it matters less what the season is than that the air is almost seasonless – benign and neutral, windless, devoid of heat or cold.

I heard from afar, across the withering late summer meadows, the jingle of a cowbell like eternity piercing my heart with a sudden intolerable awareness of the eternity of the imprisoning years stretched out before me: it is hard to describe the serene mood which, even in the midst of this buzzing madness, would steal over me when as if in a benison of cool raindrops or rushing water I would suddenly sink away toward a dream of Isiah….

‘Yam, me tek 'ee dar, missy, me tek 'ee dar.’ I listened closely. It was blue-gum country-nigger talk at its thickest, nearly impenetrable, a stunted speech unbearably halting and cumbersome with a wet gulping sound of Africa in it.

It was always a nameless white girl between whose legs I envisioned myself – a young girl with golden curls […] when I stole into my private place in the carpenter's shop to release my pent-up desires, it was Miss Emmeline whose bare white full round hips and belly responded wildly to all my lust and who, sobbing ‘mercy, mercy, mercy’ against my ear, allowed me to partake of the wicked and godless yet unutterable joys of defilement.

“Ve a Jerusalem y marca la frente de los hombres que suspiran y lloran a causa de todas las abominaciones que allí ocurren… Mátalos a todos, a viejos y jóvenes, a doncellas, mujeres y niños, pero ni siquiera te acerques a los que llevan la marca.”Lo primero que tienen que saber de Nat Turner es que no es lo mismo que un carro, aunque ambos sean bienes muebles susceptibles de venderse o alquilarse por horas. También es importante entender que Nat Turner, aun siendo negro, estaba dotado de libre albedrío y voluntad, de tal forma que, a diferencia del carro, las consecuencias de sus actos no eran responsabilidad de su amo y que, por tanto, podía ser juzgado por ellos. Y lo más importante, Nat Turner encabezó la rebelión más sangrienta de esclavos negros contra la esclavitud en EE.UU, una rebelión fracasada por la que fue juzgado y condenado a morir en la horca.

“Criados, obedeced a vuestros amos con todo temor, y obedeced no sólo a los amos buenos y amables, sino también a los perversos… cuantas faltas cometéis para con vuestros amos y amas, son faltas que cometéis contra el mismísimo Dios, quien en sus designios os ha dado estos amos y amas, y espera que os portéis para con ellos de igual manera que os portaríais para Él mismo.”Por mi parte, solo puedo entender las críticas en virtud de la sacralidad que llegan a alcanzar los mitos, los símbolos, de una lucha por lo demás justa y necesaria. Solo desde esa perspectiva cuasi religiosa puede entenderse que alguien como Nate Parker, director de El nacimiento de una nación, otra visión de los mismos hechos narrados en la obra de Styron, pueda llegar a ver en el personaje de la novela a “un lunático sexualmente perturbado cuya única motivación dependía de sus lujurias incontrolables para las mujeres blancas, y un rebelde que carecía de un verdadero propósito o inteligencia.”

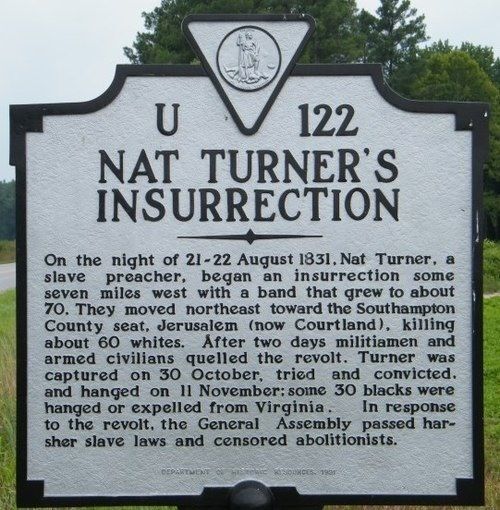

"Nearby, in August of 1831, a fanatical slave named Nat Turner led a bloody insurrection that caused the death of fifty-five white people. Captured after two months in hiding, Nat was brought to trial in the county seat of Jerusalem (now Courtland) and he and seventeen of his followers were hanged."

Why? It is perhaps impossible to explain save by God, who knows all things. Yet, I will say this, without which you cannot understand the central madness of nigger existence: beat a nigger, starve him, leave him wallowing in his own shit, and he will be yours for life. Awe him by some unforeseen hint of philanthropy, tickle him with the idea of hope and he will want to slice your throat.There are many lyrical passages in Styron's Pulitzer Prize winning novel that are stunning, including contemplation of a life beyond the limits of plantation life by those who never were able to reach beyond it. Here is just one passage, with Nat Turner attempting to envision an ocean he has never seen & will never see, though it is geographically not so very far distant:

And so it comes to me, this vision, in the same haunting & recurrent way it has for many years. Again, I am in the little boat, floating in the estuary of a silent river toward the sea. And again, beyond & ahead of me, faintly booming & imminent yet without menace, is the sweep of sunlit ocean. Then the cape, then the lofty promontory, and finally the stark white temple high & serene above all, inspiring in me neither fear nor peace nor awe, but only the contemplation of a great mystery, as I move out toward the sea...For Nat Turner, descriptions of the ocean, just 40 miles away became a liberating dream, "a kind of fierce, inward, almost physical hunger & there were days when my mind seemed filled with nothing but fantasies of waves & the distant horizon & the groaning seas, the free blue air like an empire arching eastward to Africa--as if by one single glimpse I might comprehend all the earth's ancient, oceanic, preposterous splendor."

“Each of us, helplessly and forever, contains the other – male in female, white in black, and black in white. We are part of each other.”

He had the face one might imagine to be the face of an African chieftain -- soldierly, fearless, scary, and resplendent in its bold symmetry -- yet there was something wrong with the eyes, and the eyes, or at least the expression they often took on, as now, reduced the face to a kind of harmless, dull, malleable docility. They were the eyes of a child, trustful and dependent, soft doe's eyes mossed over with a kind of furtive, fearful glaze, and as I looked at them now -- the womanish eyes in the massive, sovereign face mooning dumbly at the rabbit's blood -- I was seized by rage. I heard Cobb fumbling around in the cider press, clinking and clattering. We were out of earshot. "Black toadeater," I said. "snivelin' black toadeatin' white man's bootlickin' scum! You, Hark! Black scum!"Turner's "Confession" exists. Though Turner could both read and write, this confession was taken down and written by his defense attorney, Thomas R. Gray . Although Styron questions whether this "confession" might be Gray's interpretation, he concludes that the insurrection happened as presented in this document. But there is nothing else in the official record or document that tells us about Turner's early life, nor anything further about his personality. This is a work of fiction - superb historical fiction to my thinking.

Soon, though, a group of African American writers attacked the book, accusing Styron of distorting history, of co-opting their hero, and of demeaning Turner by endowing him with love for one of his victims, a young white woman. These critics saw Styron as usurping their history, much as white people had usurped the labor and the very lives of their ancestors. They rejected the notion that a white southerner—or any white person, for that matter—could fathom the mind of a slave.

Source: http://www.enotes.com/topics/confessi...

Yet, your Honors, I will endeavor to make it plain that all such rebellions are not only likely to be exceedingly rare in occurrence but are ultimately doomed to failure, and this as a result of the basic weakness and inferiority, the moral deficiency of the Negro character.

Although I have come late to the joys of reading and still cannot properly “read,” I have known the crude shapes of simple words ever since I was six, when Samuel Turner, a methodical, tidy, and organized master, and long impatient with baking alum turning into white flour and cinnamon being confused with nutmeg, and vice versa, set about labeling every chest and jar and canister and keg and bag in the huge cellar beneath the kitchen where my mother dispatched me hourly every day. It seemed not to matter to him that upon the Negroes— none of whom could read— these hieroglyphs in red paintwould have no effect at all: still Little Morning would be forced to dip a probing brown finger in the keg plainly marked MOLASSES, and even so there would be lapses, with salt served to sweeten the breakfast tea. Nonetheless, the system satisfied Samuel Turner’s sense of order, and although at that time he was unaware of my existence, the neat plain letters outlined by the glow of an oil lamp in the chill vault served as my first and only primer. It was a great leap from MINT and CITRON and SALTPETRE and BACON to The Life and Death of Mr. Badman, but there exists both a frustration and a surfeit when one’s entire literature is the hundred labels in a dim cellar, and my desire to possess the book overwhelmed my fear.

As for myself, I was a very special case and I decided upon humility, a soft voice, and houndlike obedience. Without these qualities, the fact that I could read and that I was also a student of the Bible might have become for Moore (he being both illiterate and a primitive atheist) an insufferable burden to his peace of mind. But since I was neither sullen nor impudent but comported myself with studied meekness, even a man so shaken with nigger-hatred as Moore could only treat me with passable decency and at the very worst advertise me to his neighbors as a kind of ludicrous freak.

…

At such moments, though Moore’s hatred for me glittered like a cold bead amid the drowned blue center of his better eye, I knew that somehow this patience would get me through. Indeed, after a while it tended to neutralize his hatred, so that he was eventually forced to treat me with a sort of grudging, grim, resigned good will.

So all through the long years of my twenties I was, in my outward aspects at least, the most pliant, unremarkable young slave anyone could ever imagine. My chores were toilsome and obnoxious and boring. But with forbearance on my part and through daily prayer they never became really intolerable, and I resolved to follow Moore’s commands with all the amiability I could muster.

On Being Brought from Africa to America

'Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there's a God, that there's a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

"Their colour is a diabolic die."

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin'd, and join th' angelic train.

Phyllis Wheatley, a slave poet, 1753–1784

able to disgorge without effort peals of jolly, senseless laughter.

dreams of giant black angels striding amid a spindrift immensity of stars.

deafened as a little boy by a blow on the skull from a drunken overseer, he had since heard only thumps and rustlings.

there lurked in his heart a basic albeit leaden decency

grasshoppers stitched and stirred in restless fidget among the grass