The Maimed by Hermann Ungar wonderfully terrifying descent into paranoia, perversity and the power of abuse. Well-written and captivating from the opening sentence, this novel tells the depressing story of Franz Polzer. Ungar leads us with a perfect narrative through a tale that offers no lasting happiness for the tortured soul of Franz or those around him.Thematically, we are dealing with repression, abuse, madness, homosexuality and sadism.

Doesn't that sound like fun? Read on, brave ones.

Franz Polzer's life starts off badly and never quite recovers even though for a time, he learns to maintain a routine through his systematic organization and superstitions. After losing his mother and being repeatedly beaten at the hands of his father while his aunt held him down, Franz becomes a timid and withdrawn fellow fearing most everything and everyone. Then one night he sees his father leaving his aunt's room and believes that they are having an affair. Franz develops an intense aversion to her which is impressed upon his memory the part in her black hair contrasted with the whiteness of her scalp. This imagery sticks with him and shows up later in the book causing him paralyzing anxiety as he thinks of his landlady, Frau Porges:

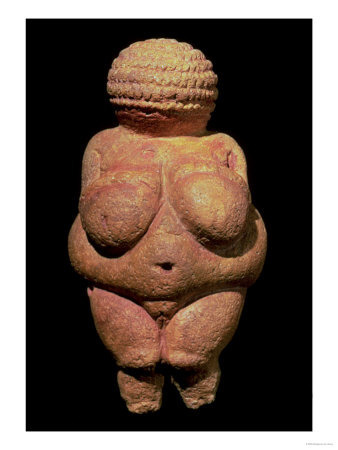

As soon as the shadow of his aunt fell across the lighted door, Polzer had known that a woman's nakedness was something horrid. Even before seeing his aunt's shadow, he was tormented by the horrible thought that her naked body was not closed. He felt the same way in the presence of Frau Porges--like he was plunging endlessly into a terrible slit. Like open flesh, like the folds as the edge of a wound. In galleries, he never wanted to see the pictures and statues of naked women. He wanted to touch the body of a naked woman. He felt it was the locus of impurity and a disgusting smell. He only saw Frau Porges during the day, when she was fully clothed. Yet he was tormented by the thought of her fat, naked body.

The one thing that saves Franz from his miserable existence is his success in his studies and the meeting of Karl Fanta, a rich boy who attends the Gymnasium with him. Ungar describes a homosexual relationship between Karl and Franz even from the beginning, "Karl Fanta saw that Polzer was unhappy, and often both boys embraced, kissing each other while they cried." In 1923, this was quite a daring work and when Ungar submitted it to Kafka's publisher at the time, although liking it, thought he would be brought up on obscenity charges if he published it. Interestingly, the relationship between Franz and Karl is the only relationship, at least for Franz, where physical intimacy is an expression of love not a an act of compliance stemming from fear. Of course, in true Eastern European style, any happiness derived from his relationship with Karl is thwarted. Karl becomes ill and is sent away for treatment. Karl's father had agreed to pay Franz's way through his University studies, but once Karl is sick, Franz is forced to leave his studies and take a clerk position in a bank.

Due to his meager finances, he is forced to rent a room from Klara Porges, the fat and 'hairy' widow. He is frightened of her and repulsed by her. He consistently obsesses over her fat and the part in her black hair that reminds him of his aunt. Even though he avoids her, she manipulates him into spending more time with her as well as sleeping with her which turns out to be a humiliating and disgusting experience:

The breasts beneath her loose blouse were already touching his body. He lifted his hands to push her away, but his fingers only grasped th heavy mass of flesh.

That evening he was able to do it.

She had put out the light and was sleeping beside him. Her arm was around his shoulders.

That night Franz Polzer was seized by a great, incomprehensible and horrible thought.

It happened suddenly. The white line made by the part in her hair shimmered palely. Her body seemed soft and dark He longed for this body, and suddenly her remembered it was the body of his sister.

He knew the thought had no foundation. He had never had a sister. But the idea was too powerful and immediate for him to dispel it.

Franz Polzer rose and wrapped himself in his coat. He sat down at the table. It was as though he had slept with his sister. He remembered the nights at home when his father's heavy steps would creak over the rotten floorboards, and he would lie in bed, overcome by horror as he listened.

As his relationship with Frau Porges progresses, it becomes more humiliating. Karl, who is now married and has a teenage son, becomes prominent once more in Franz's life. Now a paraplegic and rotting away from some unknown disease, he has become a hostile and paranoid man He confides in only in Franz and the weight of this is unpleasant and intimidating for Franz. But because of his feelings and loyalty to Karl, Franz never questions or objects. He does what is asked of him. At one point, Karl becomes so verbally abusive to his wife and son that the son, also named Franz, confides in Polzer providing another sexually confusing moment:

Polzer pulled him close. He pressed the boy's head to his chest. Franz Fanta's question had touched him For a moment his hand lay on Franz's soft hair. He pulled quickly away struck by indistinct memories of the boy' father, of the work from the assignment book, of tears of distant affection.

"I'm sure you won't get sick," he said.

"It bothers us," said Franz, "me and my mother. Mother thinks you could help us."

Polzer held Franz Fanta tight. He felt his thin limbs against his body, felt the way Franz's chest rose and fell as he breathed.

The boy looked at Franz Polzer.

Polzer avoided his eyes. He felt the boy's heartbeat. It was a face he had seen before. Dora was right. Forgotten similarities filled Polzer with consternation and anguish.

Franz Fanta said:

"Do you love me, Polzer?"

Shocked, Polzer let go of the boy.

Ungar gives us such a repressed story of homosexuality that it's difficult for the reader to ever think that Franz will find happiness. An infusion of oppression and desperation leads us from page to page, hoping that relief is soon to be found. But each of the characters in this book is truly tragic. Polzer is the ultimate victim--abuse brought on by others and fueled by his own defense mechanisms. But the others are sorrowful victims of their own self-imposed cages grasping for quickest way to feel powerful in hopes of garnering even the smallest moment of happiness. Abuse begets abuse and it was never more true than in this twisted and tragic tale of Franz Polzer.

What adds to this tragedy, are the eerily exquisite drawings by Pavel Rut. It's as if Rut has given us pencil drawings of all the people who are from the same town as the figure in Edvard Munch's The Scream. These illustrations merely enhance the sorrowful aesthetic. Hermann Ungar should be better known than he is and thanks to Twisted Spoon Press for putting this novel back in print. I am for sure going to check out the Ungar's other book, Boys and Murderers.