The year 1968 marked a turning point in American society. Marked by the assassinations of key political figures, the war in Vietnam, and a generational clash of cultures, the year is viewed by many as a key moment in history. Not even baseball could escape this clash of cultures as football was making inroads to rival it as the national sport. In 1968, baseball had been played in some iteration for over one hundred years, yet in 1968, just as in society as a whole, baseball seemed different. Sridhar Pappu writes in Year of the Pitcher how in 1968 this clash of cultures between the owners rooted to yesterday and the players with an eye on the future played one last season of baseball’s golden age.

It had been twenty years since Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier and a good ten since he walked away from a game that had given him so much. In the ten years away from baseball, Robinson had become a political activist, supporting whichever candidate in a given year he felt would do the most for the black community. Although the civil rights act had finally been enacted, for a large part it was in name only. African Americans, Robinson included, were still stopped for driving and standing in hotel lobbies as many Caucasian in the older generation still detested blacks making inroads in society. Race relations came to a head in 1968 on April 4 with the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr; after all the good Dr King did, he was still shot down, setting off a wave of rioting in cities across the country. The start of baseball season would be delayed for three days out of respect for Dr King, and due to the fact that twenty years after Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier, a large number of baseball’s stars were black. Even the backward thinking commissioner predicted a fallout if the season started as planned.

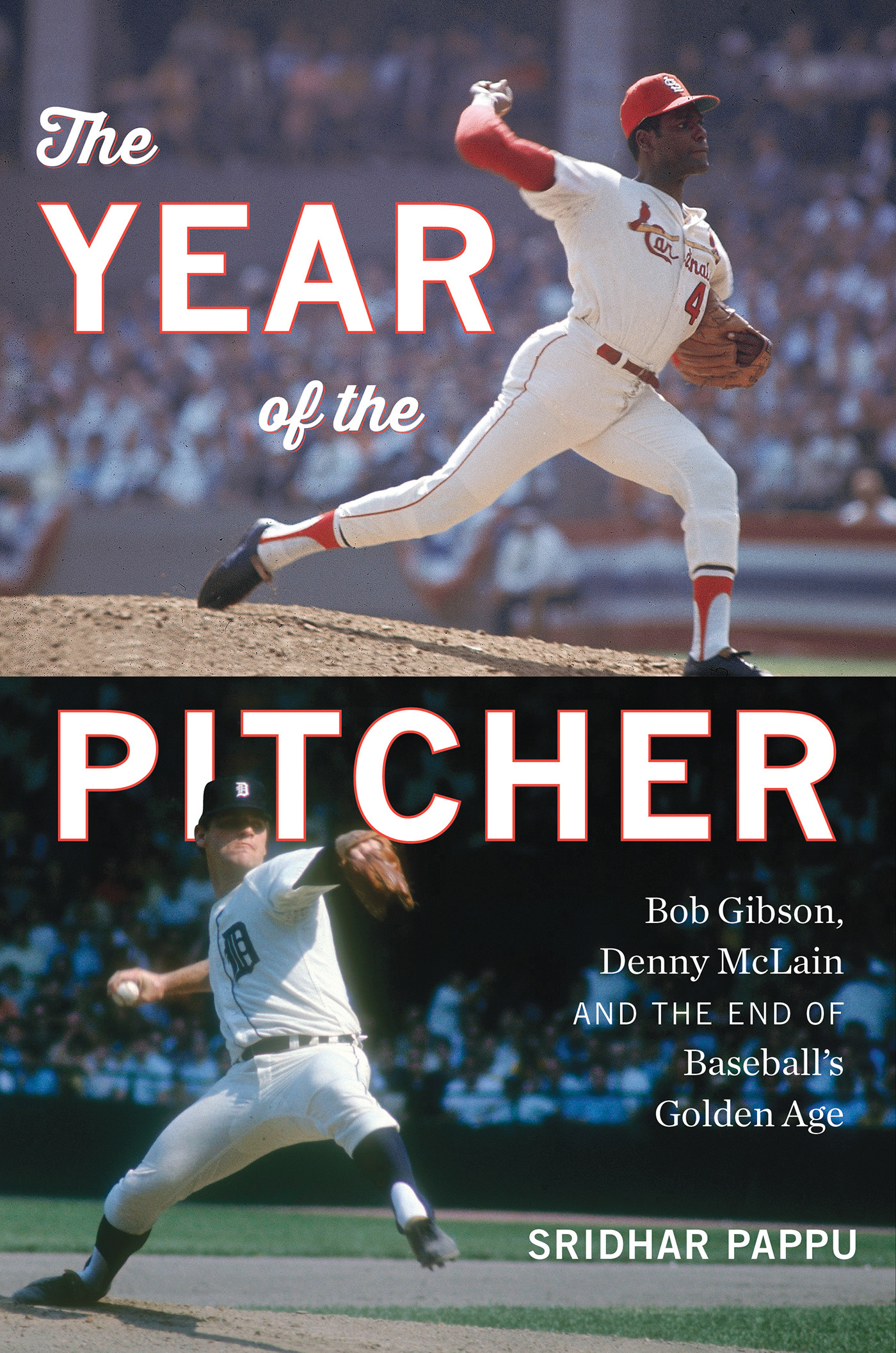

The season did not start on time for baseball players who were members of the National Guard, who had been asked to patrol the streets to help quell rioting. One notable player was Detroit Tigers pitcher Mickey Lolich, who had lead his team to just short of the pennant the year before. The Tigers believed that 1968 was their year, and Michigan’s governor had hoped that a pennant and hopefully a World Series victory would galvanize a city marred by frayed race relations. Led by franchise leader Al Kaline and an improbable thirty game winner Denny McClain, the Tigers looked to be the team to beat. Tutored by expert pitching coach Johnny Sain and a manager who did nothing in Mayo Smith, the Tigers looked to be on their way to avenging the sting of the previous year’s just falling short. Yet, they would have to beat a formidable foe in order to do so.

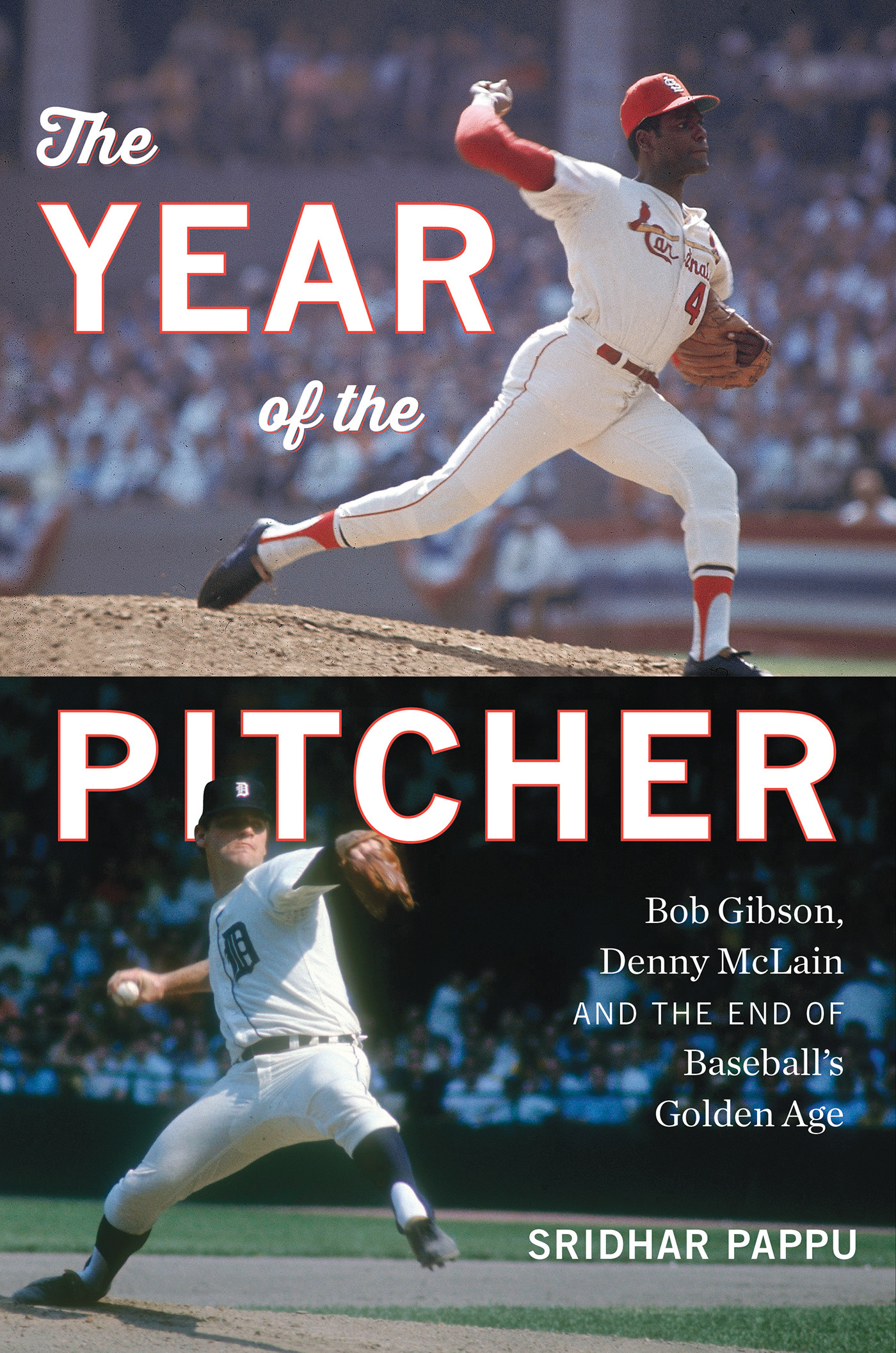

No team in the late 1960s embodied the black athlete more so than the St Louis Cardinals. Led by ace pitcher Bob Gibson and star outfielders Lou Brock and Curt Flood, African Americans saw this team as one who they could cheer for. At the time, black athletes in all sports had began to mobilize politically, led by boxer Muhammed Ali and Olympic sprinters Tommy Smith and John Carlos. Gibson suffered many indignities in life due to the color of his skin, losing out on college scholarships and endorsement deals. He was often misconstrued by the media who saw him as an angry black man. Gibson may have been angry but during his playing career chose not to get involved politically. He was an ace pitcher rivaling Dodgers star Don Drysdale and Giants ace Juan Marichal for the title of best pitcher in baseball. In 1968, all three men were deserving: Drysdale for 58 2/3 scoreless innings, Marichal for his 25 wins, and Gibson for his 1.12 ERA and leading his team to back to back pennants. With a lineup boasting future Hall of famers, the Cardinals looked to be the team to beat in the World Series.

Pappu writes that 1968 was the year of the pitcher. It was a year that saw pitchers put up numbers that will probably never be broken. Yet, 1968 will also be remembered as the last year of baseball’s golden era where hall of fame players stayed with their own team for entire careers. Baseball realized that football was a threat. With a dynamic commissioner, glitzy star players, and a new title game called the Super Bowl, football looked to be America’s sport of the future. Starting in 1969, baseball would expand by four teams and have a league championship series leading up to the World Series. Not only would pennant races become more exciting, but there would be more revenue generated by television. Yet, even in 1968, all World Series games were played during the day when kids were at school and their parents at work. Televising all the games would be meaningless if few people watched, and baseball would lose revenue in favor of football. Pappu briefly mentions the Cardinals’ Curt Flood and his fight against the reserve clause. Although not resolved in 1968, Flood’s stance would lead to free agency and player movement, making baseball in 1970s starkly different than the game played during its golden age.

Following the 1968 season, baseball lowered the pitching mounds to compensate for pitchers’ dominance. Gibson continued to put up hall of fame credentials but McClain faded and got into trouble with money laundering schemes. By 1972 there were still no African American managers, and Jackie Robinson called out baseball to break down more racial barriers going forward in order for it to truly remain as America’s game. Sridhar Pappu maintains that the racial tensions along with the stellar pitching came to a head in 1968, a year marked by death’s of prominent Americans, a war, and Nixon’s first election victory. The year would be known in baseball circles for remarkable pitching, the likes of which will probably not be seen again, and the end of baseball as a wholesome game cemented as the one sport that all Americans believed to be its national pastime.

4.5 stars