What do you think?

Rate this book

A Primeira Guerra Mundial – que acabaria com as guerras

No centenário de um dos conflitos que marcou a história do século XX, a Globo Livros lança "A Primeira Guerra Mundial", considerado um dos melhores lançamentos do ano em não ficção por publicações como The New York Times Book Review, The Economist, Bloomberg Businessweek e The Globe and Mail. O livro conquistou em 2014 o prestigiado Political Book Award, na categoria "Questões Internacionais".

Com descrições detalhadas, Macmillan analisa como a Europa de 1900 foi de um clima de confiança no progresso e no futuro a um conflito que mataria milhões de pessoas, sangraria as economias e acirraria as rivalidades nacionais. A autora se debruça sobre o período entre o início do século 19 até o assassinato do arquiduque Franz Ferdinand, herdeiro do trono austro-húngaro, para investigar as transformações políticas e tecnológicas, as decisões de estado e os deslizes da natureza humana que resultaram na guerra. Uma leitura fluída e prazerosa, "A Primeira Guerra Mundial" é uma obra de referência, fundamental para compreender eventos que definiram os rumos do século XX.

A historiadora Margaret MacMillan é uma referência internacional nos estudos sobre a Primeira Guerra e recebeu recentemente o Harbourfront Festival Prize, prêmio concedido pelo International Festival of Authors (IFOA), realizado em Toronto, no Canadá. A premiação já foi concedida outra renomada autora canadense, a vencedora do Prêmio Nobel de Literatura 2013, Alice Munro.

O texto resgata líderes políticos, diplomatas, militares, banqueiros e, sobretudo, cabeças coroadas que à época ainda mantinham laços familiares de longa data. E conta como todos – do impulsivo kaiser Wilhelm II ao imperador da Áustria-Hungria Franz Joseph, do czar Nicolau II ao rei inglês Edward VII – não conseguiram interromper a escalada de hostilidades. O amplo retrato produzido pela autora não deixa de citar, também, personalidades que fizeram alertas em favor da paz. Entre elas, o cientista Alfred Nobel, a escritora e ativista Bertha von Suttner (a primeira mulher a receber o Prêmio Nobel da Paz) e uma estrela em ascensão na política britânica: Winston Churchill.

Narrado com desenvoltura, o livro mantém o leitor agarrado ao desenrolar da história, ligando os fios entre os acontecimentos e revelando como decisões de alguns poucos poderosos podem determinar o destino de um povo e de vários países. Íntima dos bastidores do poder, Madeleine Albright, ex-secretária de Estado do governo Clinton, foi enfática ao opinar sobre o trabalho de McMillan: "Este é um dos melhores livros que já li sobre as causas da Primeira Guerra Mundial".

1056 pages, Kindle Edition

First published October 1, 2013

Germany’s pavilion was surmounted by a statue of a herald blowing a trumpet, suitable perhaps, for the newest of the great European powers. Inside was an exact reproduction of Frederick the Great’s library; tactfully, the Germans did not focus on his military victories, many of them over France. The western façade hinted, though, at a new rivalry, the one which was developing between Germany and the world’s greatest naval power, Great Britain: a panel showed a stormy sea with sirens calling and had a motto rumored to be written by Germany’s ruler, Kaiser Wilhelm II, himself: “Fortune’s star invites the courageous man to pull up anchor and throw himself into the conquest of the waves.” Elsewhere at the Exposition were reminders of the rapidly burgeoning power of a country that had only come into existence in 1871; the Palace of Electricity contained a giant crane from Germany that could lift 25,000 kilos…

The problem confronting [Chief of Staff Alfred von Schlieffen] was that the alliance between France and Russia which was developing throughout the 1890s presented Germany with the nightmare possibility of war on two fronts. Germany could not afford to divide its forces to fight all-out wars on both of those fronts so it would have to engage in a holding action on one side while it struck hard on the other to gain a quick victory. “Germany must strive, therefore,” he wrote, “first, to strike down one of these allies while the other is kept occupied; but then when the one antagonist is conquered, it must, by exploiting its railroads, bring a superiority of numbers to the other theater of war, which will destroy the other enemy.” While he initially thought of striking first at Russia, Schlieffen had changed his mind by the turn of the century: Russia was strengthening its forts to give it a strong defensive line running north to south through its Polish territories and building railways which would make it easier to bring up reinforcements…It made sense, therefore, for Germany to stay on the defensive in the east and deal with Russia’s ally France first.

“We also remember the Great War because it was such a puzzle. How could Europe have done this to itself and to the world? There are many possible explanations; indeed, so many that it is difficult to choose among them. For a start the arms race, rigid military plans, economic rivalry, trade wars, imperialism with its scramble for colonies, or the alliance system dividing Europe into unfriendly camps. Ideas and emotions often crossed national boundaries: nationalism with its unsavoury riders of hatred and contempt for others; fears, of loss or revolution, of terrorists and anarchists; hopes, for change or a better world; the demands of honour and manliness which meant not backing down or appealing weak; or Social Darwinism which ranked human societies as if they were species and which promoted a faith not merely in evolution and progress but in the inevitability of struggle. And what about the role of individual nations and their motivations: … How did these all play their part in keeping Europe’s long peace or moving it towards war?“

“It was Europe’s and the world’s tragedy in retrospect that none of the key players in 1914 were great and imaginative leaders who had the courage to stand out against the pressures building up for war.”

July 1914: Countdown to War by Sean McMeekin, I would recommend this as a companion; it differs in conclusions and some focus areas but offers a compelling account, too. [My review: https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...]

July 1914: Countdown to War by Sean McMeekin, I would recommend this as a companion; it differs in conclusions and some focus areas but offers a compelling account, too. [My review: https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...] The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 by Christopher Clark, which is another highly recommended account published in 2014 like MacMillan's and McMeekin's for the WWI centenary.

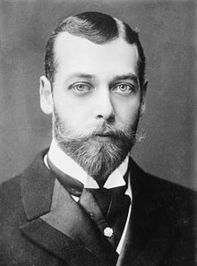

The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 by Christopher Clark, which is another highly recommended account published in 2014 like MacMillan's and McMeekin's for the WWI centenary. King George V

King George V  Kaiser Wilhelm II

Kaiser Wilhelm II  Tsar Nicolas II

Tsar Nicolas II Tsarina Alexandra

Tsarina Alexandra"What was dangerous for the future was that each of Austria-Hungary and Russia was left thinking that threats might work again. Or, and this was equally dangerous, they decided that next time they would not back down." (p.499)Thus when the assassination in Sarajevo occurred and Austria made impossible demands of Serbia in retaliation, nobody was inclined to back down. The multiple alliances that had developed over the years complicated matters.

"By 1914 the alliances, rather than acting as brakes on their members, were too often pushing the accelerators. (p. 531)"The following are some of my observations about the history described by this book:

"The Great War was not produced by a single cause but by a combination and, in the end, human decisions."In other words, it's complicated. This is a long book (32 hours in audio format) and once again shows that the more one learns about history the less clear cut become the reasons for directions taken.

Peacemakers: The Paris Conference of 1919 and Its Attempt to End War

Peacemakers: The Paris Conference of 1919 and Its Attempt to End War  The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 by Christopher Clark

The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 by Christopher Clark