What do you think?

Rate this book

312 pages, Hardcover

First published March 18, 2004

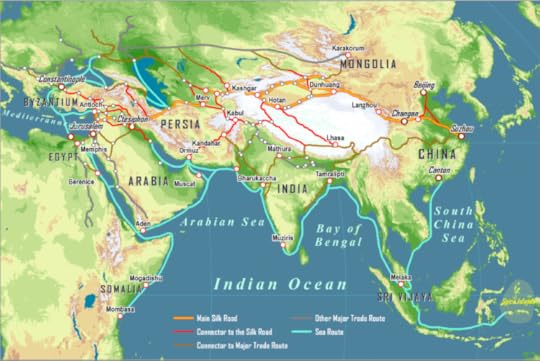

The Black Sea was at the center of an economic network that extended from the mulberry groves of China to the silk houses of Marseilles from the fairs of Novgorod and Kiev to the bazaars of Tabriz…Map of 8th-11th century trade routes along the Volga, shown in red, and via a complex river and portage route linking the Baltic with the Dnieper and the Black Sea, shown in blue.

Overland routes carried goods from China through central Asia and Persia to Trebizond. The rivers of the north carried traffic through Poland and Russia to the Baltic Sea bearing silk, fur and animal hides to the growing towns of northern Europe….

A merchant could start his journey in Genoa or Venice, sail half way across the Mediterranean, through the Straits and over the Black Sea, and at the end of it share a glass of wine with another Italian, probably even someone he knew. If a European importer could bring his Chinese silk or Indian spices as far as the Black Sea, they were almost home…get your merchandise to the Black Sea and you could get it anywhere in the world.

The Ottomans were originally an unremarkable frontier dynasty, a combination of Turkoman nomads and Byzantine farmers, some perhaps converted to Islam, others still Christian, along with itinerant traders, Muslim scholars and Greek and Armenian and other townsmen—little different, in fact from the mixed cultures of the other Turkoman frontier emirates across Anatolia.The Unpeopling of the Black Sea

...none of the great battles of the fourteenth century, including the famous encounter at Kosovo field in June 1389 involved only Muslims on one side and only Christians on the other.

Most importantly, no early Byzantine account ever mentions the Ottoman’s alleged desire to conquer for their faith…The idea of warriors for Allah fighting the infidel is in fact a product of later Ottoman historians. Once the Ottomans acquired a real empire in the late 1300s and 1400s—with the conquest of the Balkans and finally of Constantinople—they had to manufacture a vision of their past that recast their heterodox nomadic ancestors as pious Muslims. Later European historians simply accepted whole cloth the Ottomans’ own propaganda.

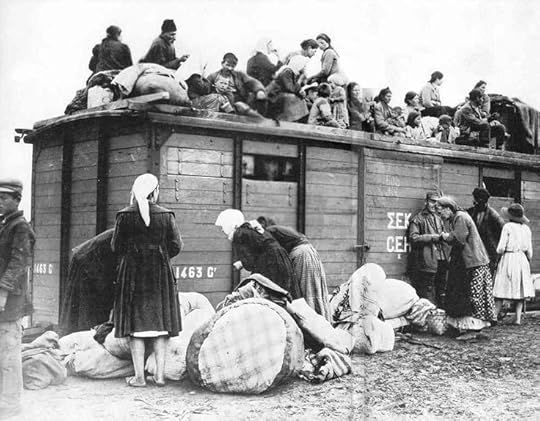

The forced movement of people, as refugees from armed conflict or as settlers uprooted by governments and planted again in new territories, is nothing new around the Black Sea....In antiquity, the port cities were places of punishment for impious poets and political dissenters. In the Ottoman period, the exile of entire villages, known as sürgün, was used as a punishment or as a form of colonization to populate low-density areas.In the early 1860s as Russia moved into the Caucasus highlands, villages were systematically emptied and hundreds of thousands of nominally Muslim highlanders—Circassians, Chechens, and others—were dispatched by ship to Ottoman ports. The Ottomans in turn moved the refugees on to “resettlement areas on their own restive frontiers in the Balkans, eastern Anatolia, and the Arab lands.”

Similar policies were adopted as the Russian empire expanded south in the 18th and 19th centuries. Tartar, Greeks, and Armenians were moved out of Crimea, and Slavic peasants were moved south to help settle the New Russian steppe

From the middle of the 19th century, organized population transfers both accelerated and changed in nature. Moving people could be accomplished more easily [via rail and steamship]….There was a new philosophical impetus as well. The rise of nationalism, first as a cultural movement among European-educated intellectuals and then as a state policy that linked political legitimacy with the historical destinies of culturally defined nations provided an additional reason for moving people from one place to another.