What do you think?

Rate this book

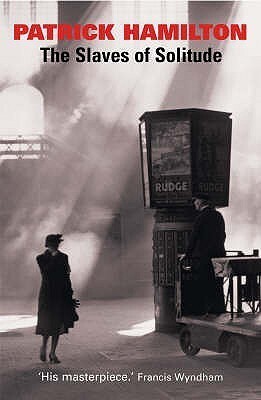

238 pages, Kindle Edition

First published January 1, 1947

Thus looked at from outside, these guests – in this dead-and-alive dining-room, of this dead-and-alive house, of this dead-and-alive street, of this dead-and-alive little town – in the grey, dead winter of the deadliest part of the most deadly war in history – thus seen from a detached point of view, they presented an extraordinary spectacle.

They didn’t talk, they didn’t laugh, they didn’t seem to enjoy their food, they didn’t seem to go out, they didn’t seem to have any interests, they didn’t seem to like each other much, they didn’t even seem to hate each other, they didn’t seem to do anything. All they seemed to do was to crawl in one by one, murmur a little to the waitress, mutter little requests to pass the salt, shift in their chairs, occasionally modestly cough or blow their noses, sit, eat, wait, eat, sit, and at last crawl out again, one by one…

'Old Roach.' 'Old Cockrock.' Driven out on to the streets, and walking about in the blackness, as she had done that night, months ago, before all this had begun. 'Old Cockroach.' That was her. That was how they had started with her, and that was how it would always be. She might have known this- she might have known better than to have suspected the possibility of any brighter destiny.

If she hadn't cried herself out already, she could go back and cry. But she had cried herself out. It was all over now- even tears.

And, observing the purification of Mr. Prest, Miss Roach herself felt purified. She would have been surprised, a few months ago, if someone had told her that she was one day going to be purified by Mr. Prest- that that forlorn, silent man in the corner, that morose wearer of plus-fours, that slinker to his room, that stroller to the station, that idler and hanger-about in bars, had within him the love of small children and the gift of public purification!

‘I said,’ he said, looking at her, ‘your friends seem to be mightily distinguishing themselves as usual.’

‘Who’re my friends?’ murmured Miss Roach.

‘Your Russian friends,’ said Mr Thwaites.

‘They’re not my friends,’ said Miss Roach, wrigglingly, intending to convey that although she was friendly with the Russians she was not more friendly than anyone else, and could not therefore be expected to take all the blame in the Rosamund Tea Rooms for their recent victories.

‘The Coalman, no doubt, will see fit to give commands to the King,’ he said, ‘and the Navvy lord it gaily o’er the man of wealth. The banker will bow the knee to the crossing sweeper, I expect, and the millionaire take his wages from the passing tramp.’

‘At least,’ he said, looking straight at Miss Roach, ‘that’s what you want isn’t it?’

Alone in the distance, lost in the wind, this obsessed figure, requiring, really, a Wordsworth to suggest the quality of its mystery and solitude.