What do you think?

Rate this book

116 pages, Kindle Edition

Published January 22, 2017

"When Edward and I were in penury, kept chained together by want, and abhorring each other for the very compulsion of our union, I used to endure worse torments than those of hell. Edward overwhelmed by his strength and bulk. He used his power coarsely, for he had a coarse mind, and scenes have taken place between us [of] which remembrance to this day, when it rushes upon my mind, pierces every nerve with a thrill of bitter pain no words can express."

-- Sir William Percy, in Charlotte Brontë's 'The Duke of Zamorna' (1838)

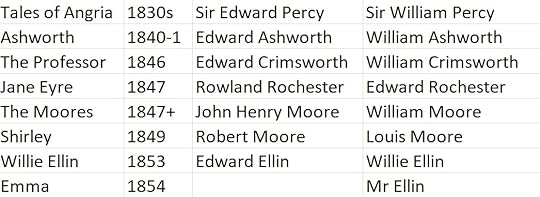

The Two Brothers strand in Charlotte Bronte's writings

The Two Brothers strand in Charlotte Bronte's writingsMr Ashworth was a man much known about the country some years ago. But in the West Riding of Yorkshire where most of his public exploits were performed, his private history remains to this day in a great measure a mystery.

... Mr Arthur Ripley West. We may as well introduce him at once without further parade and also announce that he is going to be our hero, for if we did not reveal this secret, the reader would soon find out.

* Thornton in West Yorkshire is of course where Charlotte was born, and which even might have inspired the name Thornfield where Jane Eyre met Rochester