What do you think?

Rate this book

224 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 2018

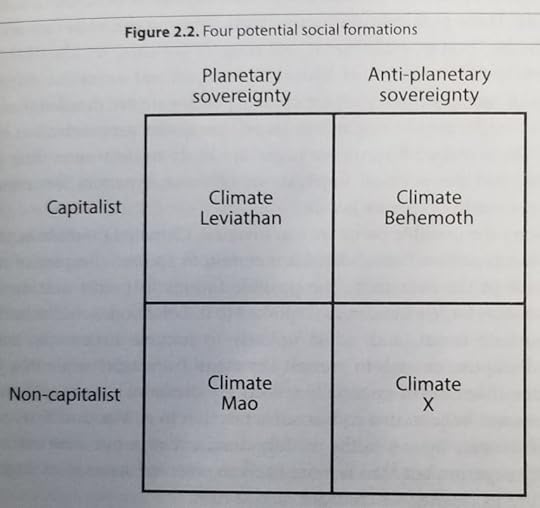

…Climate X is a world that has defeated the emergent Climate Leviathan and its compulsion toward planetary sovereignty, while also transcending capitalism. This is obviously a tall order… (173)(X here is the unknown in math, as well as a kind of lexical refusal of order.)

Leviathan's sovereignity is posited as nothing less than the functional social adaptation to the state of nature. This thread ties the entire Western European tradition of political theory together. Historically, appeals to nature and biology are always used to justify and secure the position of the prevailing elite. Nature sides with the powerful.

None of this is to deny the value of scientific study of nature, the legitimacy of evolutionary theory, or valid uses of the concept 'adaptation' in social and political analysis. We are all subjects of ideology. No one can wholly rejects ones conceptual inheritance any more than one can wholly refuse the knowledge it affirms. But grave problems arise when we forget the irrevocably metaphorical quality of all natural and biological concepts that circulate in political life.

To address its contradictions - including the ecological contradiction that capital's growth is destroying the planet - capitalism needs a planetary manager, a Keynesian world state. But elites have proven reluctant to build it, and it appears unlikely to miraculously realise itself. So, the only apparent capitalist solution to climate change is presently impossible; the only even marginally possible green Keynesianism that could save us is still predicated upon the territorial nation-state.