What do you think?

Rate this book

407 pages, Paperback

First published October 25, 2016

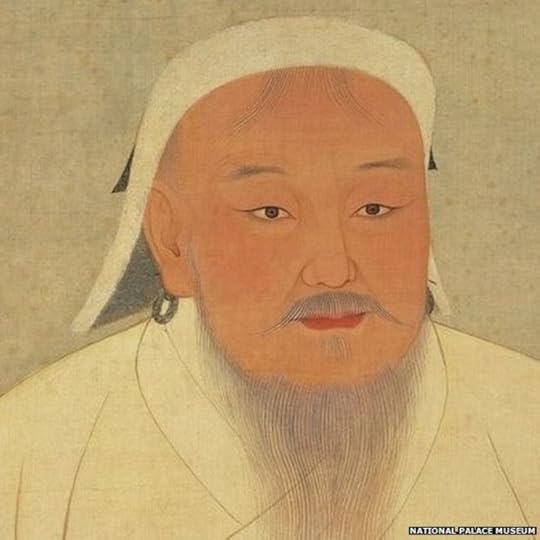

In his discussion of Genghis Khan’s career, Gibbon inserted a small but provocative footnote, linking Genghis Khan to European philosophical ideas of tolerance and, surprisingly, to the religious freedom of the emerging United States.The journey of a thousand miles begins with but a single steppe. (sorry) In this case the author’s twelve-year sojourn began with a single footnote (among about eight thousand) in Edward Gibbon’s six-volume history of the Roman Empire. Was it possible that the notion of religious freedom that has been a hallmark of the United States since its inception as a nation (despite the many over the years, and even today, who seek to impose their religious views on the secular country) was inspired, at least in part, by the notorious Mongol conqueror? Well, as that famous champion of religious freedom, Sarah Palin, might say, “you betcha.”

As a child I became engrossed in reading about Marco Polo, Kublai Khan, Genghis Khan and developed a fascination with Mongolia. In college I tried to go to Mongolia to continue that interest, but the Cold War prevented it. I put aside that interest and continued with others that I had, but when Mongolia opened in the 1990's I went to visit more out of curiousity than for any planned work. Once there, the passion of my childhood flamed higher than ever. Although I did not speak the language I felt spiritually, intellectually and emotionally at home. - from the Asia East interview