What do you think?

Rate this book

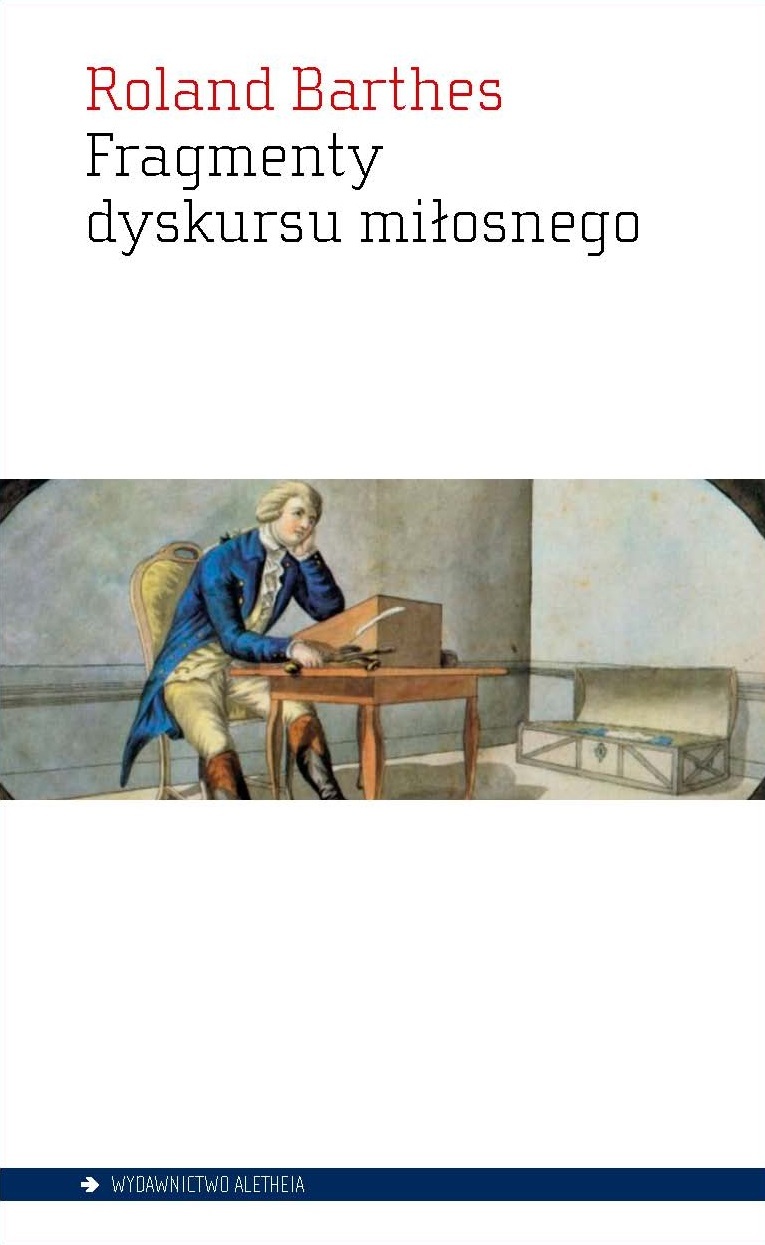

378 pages, Paperback

First published April 1, 1977

‘I have projected myself into the other with such power that when I am without the other I cannot recover myself, regain myself: I am lost, forever.’

‘If I acknowledge my dependency, I do so because for me it is a means of signifying my demand: in the realm of love, futility is not a "weakness" or an "absurdity": it is a strong sign: the more futile, the more it signifies and the more it asserts itself as strength.’

‘Absence is the figure of privation; simultaneously, I desire and I need. Desire is squashed against need: that is the obsessive phenomenon of all amorous sentiment.’

‘Isn’t the most sensitive point of this mourning the fact that I must lose a language — the amorous language? No more ‘I love you’s.’

Am I in love? --yes, since I am waiting. The other one never waits. Sometimes I want to play the part of the one who doesn't wait; I try to busy myself elsewhere, to arrive late; but I always lose at this game. Whatever I do, I find myself there, with nothing to do, punctual, even ahead of time. The lover's fatal identity is precisely this: I am the one who waits.Perhaps this book, novelistic essay or essayistic novel, must be read in one's prime, when one is in the throes of passion, to feel the full emotional impact - I do not know if this is the case. As a young man I am always on the precipice of romantic disaster, only in utter solitude, removed from all passionate enterprises, do I feel free from the pharmacopoeia (half-poison, half-remedy) of love. Bliss and misery are the Janus faces of life, in love, in solitude, we cannot have one without the other, even if they only look at us in turns.

The world subjects every enterprise to an alternative; that of success or failure, of victory or defeat... Flouted in my enterprise (as it happens), I emerge from it neither victor nor vanquished: I am tragic.Love, life, and death, are infinite, they are the lands of contradictions, beyond the capacity of language. What is both bliss and misery? What is the concatenation of victory and failure? How does die and yet endure? At these interstices of language lies the fundamental truths of Love.

To try to write love is to confront the muck of language; that region of hysteria where language is both too much and too little, excessive (by the limitless expansion of the ego, by emotive submersion) and impoverished (by the codes on which love diminishes and levels it).In front of Love, language is reduced to muck, it is inadequate. Barthes is torn between the deities of Eros and Logos - Love and Language. As a humbled votary genuflecting to the altar of Language, he is prostrate before the temple of Love.

Language is a skin: I rub my language against the other. It is as if words instead of fingers, or fingers at the tip of my words. My language trembles with desire.

To try to write love is to confront the muck of language: that region of hysteria where language is both too much and too little, excessive.

Language is a skin: I rub my language against the other. It is as if I had words instead of fingers, or fingers at the tip of my words. My language trembles with desire. The emotion derives from a double contact: on the one hand, a whole activity of discourse discreetly, indirectly focuses upon a single signified, which is "I desire you," and releases, nourishes, ramifies it to the point of explosion (language experiences orgasm upon touching itself); on the other hand, I enwrap the other in my words, I caress, brush against, talk up this contact, I extend myself to make the commentary to which I submit the relation endure.

How does a love end?-- Then it does end? To tell the truth, no one--except for the others-- ever knows anything about it; a kind of innocence conceals the end of this thing conceived, asserted, lived according to eternity. Whatever the loved being becomes, whether he vanishes or moves into the realm of Friendship, in any case I never see him disappear; the love which is over and done with passes into another world like a ship into space, lights no longer winking: the loved being once echoed loudly, now that being is entirely without resonance (the other never disappears when and how we expect). This phenomenon results from a constraint in the lover's discourse: I myself cannot (as an enamored subject) construct my love story to the end: I am its poet (its bard) only for the beginning; the end, like my own death, belongs to others; it is up to them to write the fiction, the external, mythic narrative.