What do you think?

Rate this book

164 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1975

"To start with, the book is persistently about narrative [duh!], and the more embracing topics on linguistics and literary theory [tsk tsk], all approached with characteristically French emphases [bloody Frogs, at it again]. It is crammed [really, I like my theory like weak tea] with allusions to "texts," [funny that], "semiotics," [should it be obscuriotics?] Chomsky [who?], Tristram Shandy [dratted digressions!], I Promessi Sposi [hyper messy suppose I? What is this? Desperanto spelling?], and phrases like "narrative matrix" [double duh!] and "linearity of the text"; Frank Kermode himself secures a mention [not half jealous are we?]. Part of its material is none other than French academic talk about all those matters [and that's just so passe], and the figure of Christine Brooke-Rose in her actual French academic function [as opposed to her imagined one?]--as a teacher at Vincennes [invited, no less, by Hélène Cixous]--is constantly before us [lucky dude!]. This identity is established yet more firmly by the Frenchly chic photograph of the writer on the cover, her foulard arranged to display "Saint Laurent" in the V of her dress [no sexist or xenophobic commentary there, by gov?!?!]. The trouble here is partly the [Verbi]voraciousness of "semiotics" itself...I also doubt if it is appropriate to speak of this work as a "narrative" except by courtesy [demonstrably lacking]."Michael "sour grapes" Mason, Times Literary Supplement July 1975. So much for English wit and appreciation for the ironic.

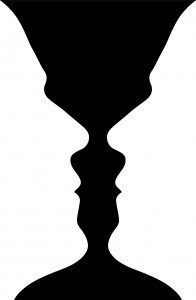

Fancy folk describe this sort of two-things-at-once image as having "plurisignificance" (which sounds like a parodist's neologism) and this is the function of the acrostics that occasionally break up the action (such as it is), along with words arranged in hoops and loops that mirror/echo the book's initial image: reflections of eyes and headlights in a rear-view mirror. These typographic antics fuse voices working at cross purposes and open the book up into a multi-vocal chattering crowd. Its members: faculty at a uni department meeting dramatizing the late-60s-early-70s campus turmoil and theory vs. traditionalism fights (and side-fights about fucking around with students); creative writing pupils with questions and comments and real-or-imagined professorial retorts; student-authored texts and professorial handwritten marginal comments whose triteness strives to match that which they critique; subjects in pain-tinged flashbacks, mostly sexual, through which a professor/student carnal exercise in impropriety undergoes all sorts of strange mutations, whereby one lover is replaced with another as if "lover" were a constant role-function and its resident subjects easily switched out ("...within the grammar of that narrative the roles can be interchanged and textasy multiplied").

Fancy folk describe this sort of two-things-at-once image as having "plurisignificance" (which sounds like a parodist's neologism) and this is the function of the acrostics that occasionally break up the action (such as it is), along with words arranged in hoops and loops that mirror/echo the book's initial image: reflections of eyes and headlights in a rear-view mirror. These typographic antics fuse voices working at cross purposes and open the book up into a multi-vocal chattering crowd. Its members: faculty at a uni department meeting dramatizing the late-60s-early-70s campus turmoil and theory vs. traditionalism fights (and side-fights about fucking around with students); creative writing pupils with questions and comments and real-or-imagined professorial retorts; student-authored texts and professorial handwritten marginal comments whose triteness strives to match that which they critique; subjects in pain-tinged flashbacks, mostly sexual, through which a professor/student carnal exercise in impropriety undergoes all sorts of strange mutations, whereby one lover is replaced with another as if "lover" were a constant role-function and its resident subjects easily switched out ("...within the grammar of that narrative the roles can be interchanged and textasy multiplied").