What do you think?

Rate this book

120 pages, Paperback

First published July 1, 1994

Syrian terrorist Monzer al-Kassar had a great setup. He ran a Frankfurt-to-New York

heroin smuggling operation that netted him millions, and the whole thing was protected

by the CIA. This was payback for serving as a middleman in Oliver North's Iran/contra

deals (see Hit #34) and also in the hope that he'd use his influence to secure the release

of US hostages in Beirut. Al-Kassar's accomplice at the Frankfurt airport regularly

substituted a suitcase full of heroin for an identical suitcase checked onto a Pan Am

flight to New York.

Major Charles McKee, a CIA agent charged with rescuing US hostages in Beirut, was

outraged when he heard of the smuggling operation, and felt it could jeopardize his

mission. He complained bitterly to the CIA, but got only silence in reply. Impulsively,

and against CIA procedures, McKee and four other members of his team decided to fly

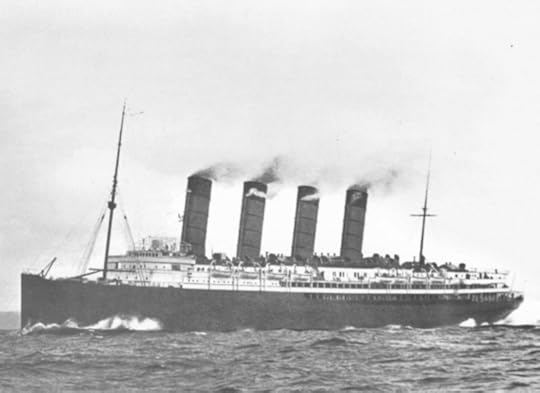

home and expose the deal with al-Kassar. Their flight connected with Pan Am Flight 103

in London.

On December 20, 1989, a German government agent in Frankfurt who was privy to the

heroin deal noticed that the switched suitcase being put onto Pan Am Flight 103 looked

completely different than it usually did. Aware that a bomb threat had been made against

the flight, he called his local CIA contact and asked what was up. "Don't worry about it,"

he was told. "Don't stop it. Let it go."

When Flight 103 left London, not only was the McKee team on board, but also a US

Justice department Nazi hunter and a UN diplomat mediating conflicts in southern

Africa. South Africa's foreign minister was booked on the flight as well, but luckily

cancelled at the last minute.

When the plane blew up over Lockerbie, Scotland, killing 270 people, a team of CIA

agents was on their way to the wreckage within the hour. Disguised as Pan Am

employees, they removed evidence from the crash site, then later returned it (or

something similar) to be rediscovered.

Initial investigations focused on Syria and Iran, with the possible motive being revenge

for an Iranian plane shot down by a US warship the previous July. But when Syria's

cooperation was needed during the Gulf War, the blame was shifted to our favorite

whipping boy, Libya ...

Pan Am conducted its own investigation, which uncovered the links to al-Kassar. But it

was unable to secure CIA documents on the case, and lost a massive lawsuit filed by the

families of Flight 103 victims. Soon after, it filed for bankruptcy.

Though investigators say they never found hard evidence of an Iranian-Palestinian conspiracy, last year, an Iranian defector to Germany gave the theory new life when he claimed the attack was ordered by Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomheini “to copy exactly what happened to the Iranian Airbus” that had been shot down by the U.S. warship.

This theory has proved durable and, for many, convincing. In its 800-page review of the Lockerbie evidence, the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission said the evidence found in the Frankfurt raid shortly before the Lockerbie bombing — including the Toshiba bomb and the flight timetable — led it to determine that “there was some evidence that could support an inference of involvement by” Palestinian terrorists.

Dr. Jim Swire, whose daughter was one of the 270 victims of Flight 103, is among those who believe Megrahi was innocent. Swire has repeatedly told reporters that he believes Iran was primarily responsible for the attack, and that the U.S. did not pursue this angle because officials wanted “to blame somebody, anybody, rather than Iran.”

Investigating the Iran link, says Swire, would have caused diplomatic problems at a time when Americans were negotiating over hostages in Lebanon...

In 2007, the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission, after more than three years of investigating, validated several of these misgivings, concluding that “some of what we have discovered may imply innocence” and referred Megrahi’s case to an appeal court in the interests of avoiding “a miscarriage of justice.”

The commission rejected several points of contention raised by critics, saying they found no signs that evidence had been tampered with, that the Libyans had been framed, or that there had been “unofficial CIA involvement” in the investigation.