Dig, if you will, this picture . . .

It's a thousand words, right? And every essay by Passarello is a couple thousand--but feel like so much more. They are dense without feeling dense, and their gravity is increased by being in what is a relatively slim volume, themes echoing and building, her thesis not fully revealing itself until the end.

What she's after, it seems to me, is what animals mean to a consciousness--whip-smart, observant--that came of age at the end of the twentieth century, when the wild had been reduced, mostly, to a few preserves, the rest heading to extinction at a massive pace, when the most exorbitant example of the wild exists in our cultural imaginings.

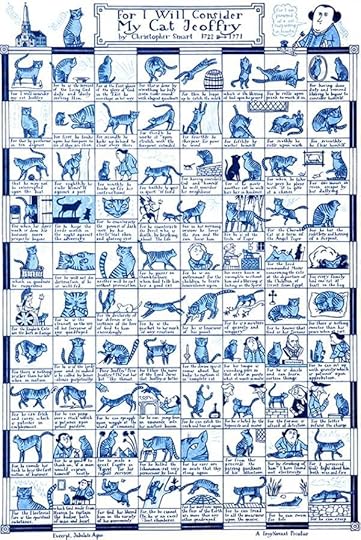

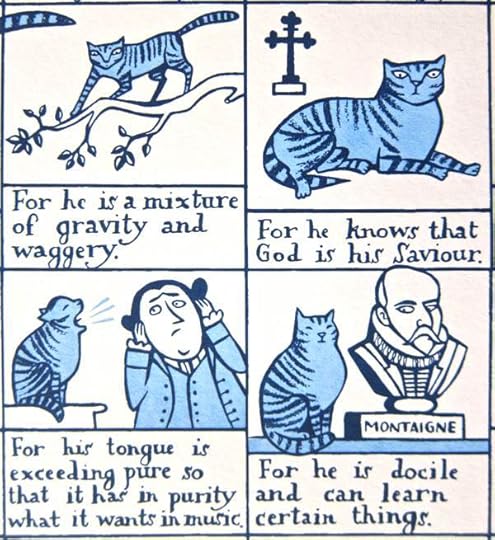

The book is a series of meditations on the theme, arranged chronologically, starting with the discovery of a mammoth that lived 39,000 years ago, and ending with a brief coda on Cecil the Lion. Across all of these, Passarello grapples with the distinction between animals as live, unpredictable things, and as representations, and where those different ways of being cross. The story of the mammoth ends with some of the earliest representations, paintings on caves; the story of Cecil is about how if the hunter knew there had been cultural importance to the lion, he'd have never killed it.

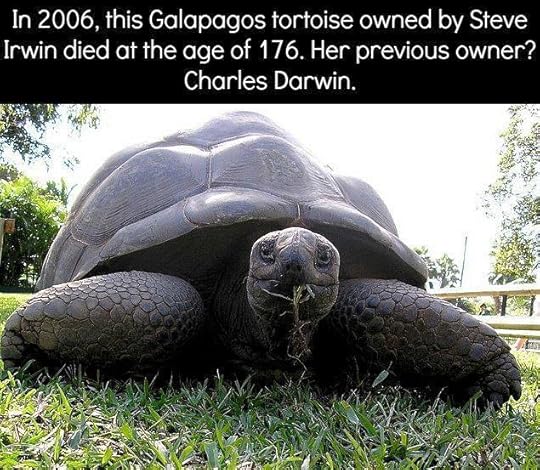

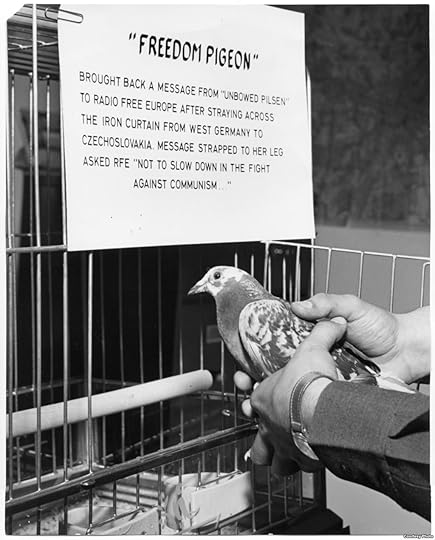

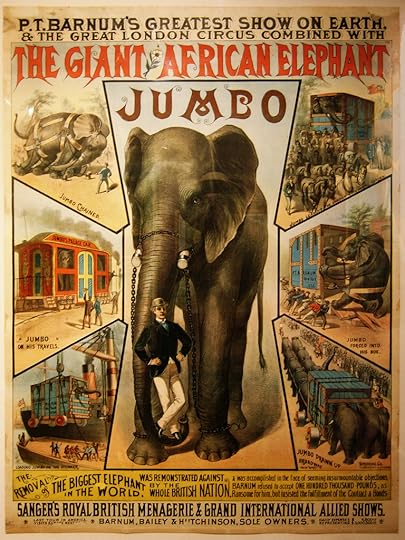

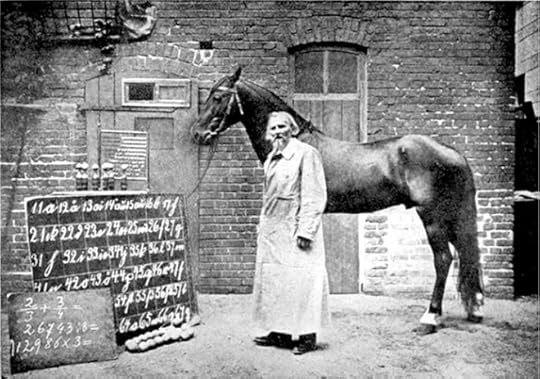

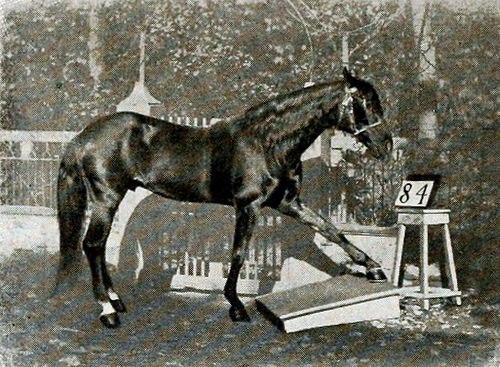

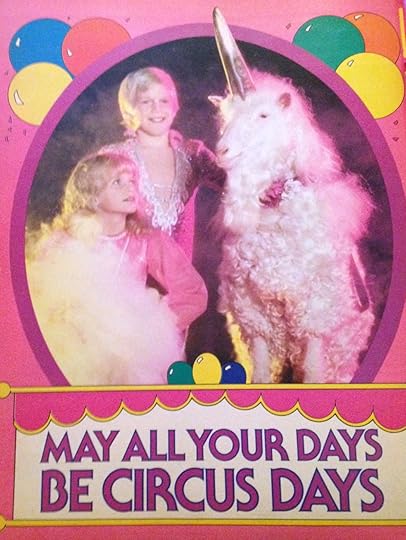

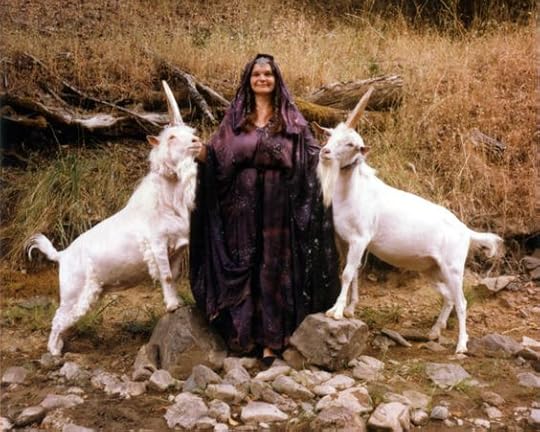

In between, she documents other contentious meetings, untangling the dense knot of representation and reality, from predatory wolves to elephants and the carceral state, from faked unicorns to pigeons in the service of war. These are experimental essays--she name checks John D'Agata in the acknowledgments, suggesting a concern for essay as lyric--and I don't always think they work: sometimes the language is too obscure; sometimes the lyricism seems to undermine the concern for simple fact; sometimes the attempt just falls flat--as when she imagines the history of Galapagos tortoise interactions with humans as failed love affairs.

But they are all worth trying, and worth reading to see a fiercely intelligent mind at play and working hard.

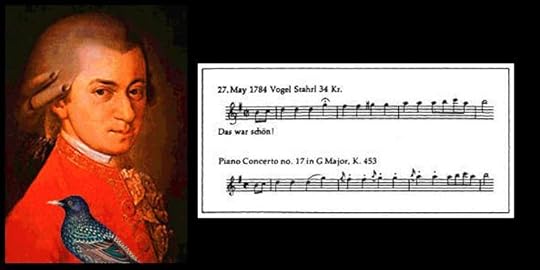

The essay on Mozart and the starling is worth the price of the book, full stop, but she adds to these others that, if not quite as cohesive, are amazingly thoughtful. I am tempted to say that she is not always serious, but that's not true--she is very serious. But she also has a sense of humor that runs toward the pornographic and scatological, which shows up here and there, most forcefully, obviously, in her chapter on Koko the Gorilla.

The title comes from the Prince song "When Doves Cry" (which also provides the first line of this review), thoguh she never makes the point. The whole song is suggestive to Passarello--doves as creatures, doves as symbols--but she pushes Prince's lyric in a slightly different direction. While the "curious" in the song modifies animal--they pose in their curiosity--here is modifies the poses: the contortions we have increasingly forced animals to take, as our representations become ever greater, and the wonder if they can push back against us or, as in the song--

"They feel the heat

The heat between me and you"--

become passive observers of our activities, looking at us, but never being seen themselves, not anymore.